also designed the slightly later buildings at the center and left.

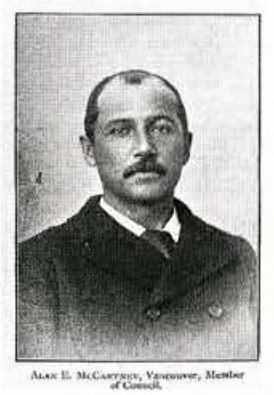

Their black Bahamian racial history, however, was not often mentioned by later members of their families. Interviewed by Vancouver’s first City Archivist, Major James Skitt Matthews in 1937 and asked about his father, Sara’s grandfather, William Edward McCartney, had said only that Alan Edward had been “born in the Bahama Islands; Irish descent.” This was true, but only partly true. Alan Edward’s grandfather, John McCartney, the Admiralty Judge for the Bahamas, had indeed been of Irish descent, but Alan’s paternal grandmother had been mostly African – quite possibly one of the approximately 40 slaves McCartney had owned on the family plantation he had inherited. When he died in 1819, all of his slaves had been in turn inherited by his Scotland-resident wife, Jane McNish, and were in 1822 recorded in the Bahamas slave register. Recently they have been recorded again by the Legacies of British Slave Ownership project together with the compensation which Jane McNish received from the British government for their being set free in 1834.

The African ancestry of the three brothers, however, appears to have been public knowledge in Vancouver during the years in which Alan and William were prominent citizens. A year before he interviewed Sara’s grandfather, Major Matthews had interviewed a Mrs Alice Crakanthorp – on 18 June, 1936 – one of numerous interviews he had held with this pioneer Vancouver resident, who had been born in 1864 on Vancouver Island. She recalled that William Ernest’s’s mother was “an Englishwoman” – all three brothers in fact had the same ethnically European mother, Ann Euterpe Rowe, according to their official Bahamas birth registrations. But Mrs. Crakanthorp also recalled Alan and Fred as having been visibly of mixed-race.

The first drug store was McCartney's, Fred and William, brothers and partners. William's mother was an

Englishwoman, but Allan [sic] McCartney, the third brother, who was tallyman at the Hastings Mill, was of

dark blood; both Fred and Allan had dark wooly hair on their heads. Their grandfather was quite 'great';

he was governor of some island, perhaps Bermuda, but I think it was Jamaica; Mrs. McCartney [she

probably meant Fanny Mann, wife of Alan] was an accomplished musician, with a diploma for singing

and teaching. (Volume 4, 114)

In 1891 Alan Edward McCartney was elected to be one of the first five directors of the new British Columbia Institute of Architects, which published this photo of him in The Canadian Architect and Builder 7, no. 10 (Oct 1894).

According to the analyses by Ancestry.com and 23andMe of the DNA of some of his living descendants, Alan McCartney could have had no more than 20% African ethnicity, and his father Henry James McCartney no more than 40%. Henry James’ “black” mother could have had no more than 75-80% African ethnicity, possibly because one of her parents was 100% African and the other 50% African and 50% European. The poorly printed black&white photo of “dark blood” Alan McCartney neither proves nor disproves Mrs. Crakanthorp’s memories of her observations– he has his “wooly” hair cut extremely short. But something else unexpected did.

In 2017 on her Ancestry DNA account my daughter received a 7-generation 19.5 centiMorgan cousin match with a female descendant of their shared ancestor, Admiralty Judge John McCartney’s grandfather, Alexander McCartney (1700-1759), of Auchinleck, Scotland. Sara and her mother’s full sister were also DNA matches to the descendant’s son, John Harrison, who managed his mother’s Ancestry DNA account. He was as surprised and puzzled by the long reach of the matches as Sara and I were. He had hoped to identify his Scottish ancestors but had not expected the route to pass through 7 generations, the Bahamas, and the African slave trade. Here is what he wrote to me.

"By my accounting, Alexander Macartney born abt 1700 is Sara’s 5th Great Grandfather, and is my 6th

Great Grandfather. This should make us about 7th or 8th cousins. What I find puzzling is this; why then

is our DNA match much higher than it should be (19.5 centimorgans over 1 segment). This is the same

amount that one would normally see with a 5th cousin. Also surprising is that Sara is a higher DNA match

with me than she is with my mother – which would seem to indicate multiple DNA sources."

"One ... possibility for the higher than expected DNA match could be this; someone else in the McCartney

or Thomson families could be a parent or grandparent of the mother of Henry James McCartney. As you

pointed out, the mother of Henry James was probably 25% white, with one parent being black, and one

parent 50/50 mix. It could be that somewhere in there, another relative could be involved? We could be

sharing DNA from another McCartney or Thomson relative that we are unaware of."

At the Bahamas National Archives Sara had no difficulty obtaining a copy of the very brief 1819 will of Admiralty Judge John McCartney, written in his own elegant handwriting and naming his wife in Scotland his sole heir and naming her and his “friend” Robert Thomson and two others to be its executors. These four were the only people he mentioned. Sara had more difficulty in finding obituaries. The archives has no holdings for 1861 issues of the Nassau Guardian, the main Nassau newspaper of record in the 19th century, 1861 being the year in which Ann Euterpe Rowe died. For May 1875 when Henry James McCartney had died, it had Guardian issues on microfilm. Scrolling through several reels, Sara did not find an obituary but did come across a news article that rather effusively announced his death and described his funeral.

We announce, with much regret, the death of H,J. McCartney, Esq, of Queen-street, in this city, which took

place at his residence on Sunday evening, at the age of 64. Mr. McCartney was a most worthy citizen,

and universally respected.. He had a seat for some years in the House of Assembly, and held a Captaincy

in the N.P. Militia. He also filled the office to the Agricultural Society established by Governor Mathew,

and was Senior Vice-President and one of the oldest Members of the St. Andrew’s Society, a Member

of the Auxiliary Bible Society and the Diocesan Church Society. As a Contractor and Builder he was second

to none, one of his latest works being Trinity Chapel in Frederick street. His remains were followed to the

family vault in Potters Field on Monday afternoon by a large concourse of persons of all classes, the

funeral service being performed by the Rev. R. Swann and the Rev. H.T.S. Castell.

Sara and I had known of his work as a building contractor, and of the graves in Potters Field (later renamed the Western Cemetery) of two of his daughters who had died in childhood, but had not known that he had been a member of the Bahamas House of Assembly nor that he had been buried in the Bahamas. On her second day in Nassau she went to the cemetery hoping that the children’s graves might provide a clue to the location of their father’s grave. They provided a very large clue – a large gravestone that matched in style those of the young girls but from which the white marble plaque that had once identified it had somehow vanished. In this photo of Sara at the cemetery one can see where that plaque had once been.

None of the numerous large buildings that Henry James McCartney's son, Alan Edward McCartney, designed and had built in Vancouver have survived. Vancouver grew quickly in the fifty years after his death and replaced substantial buildings with even larger ones long before they could be thought of as heritage structures. Most of his buildings were constructed with wood. His designs also were not especially original – they reflected the norms of Victorian architecture and moved toward the modern only when simplicity was desired by client. Here are photos of a few more more of them.

with partner Paul Marmette (1886-89, Richards St). In the middle is

the Brunswick Hotel designed by McCartney, built 1888 on Hastings

St. W., near Granville. On the right a brick commercial building

designed by McCartney for a Mrs. Gold, Water St., 1890.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed