Like Al Purdy, I also go far back in time with Earle Birney. In 1955 he signed his newly published novel Down the Long Table for my godmother to give me for Christmas; in 1957 I began seeing him, tall and slightly stooped, on the UBC campus; in my third year in 1959 I enrolled in his Chaucer class and sat in the back row where I wondered whether he ever saw me. Always theatrically self-creating, he played each day to an appreciative audience of graduate students who had preempted the front row. He savoured speculatively the Wife of Bath's portrayal, “Housbondes at chirche dore she hadde fyve, / Withouten oother compaignye in youthe,” and spent much of another class pondering new research into a rape charge that Chaucer had faced, and whether “raptus” could mean that he had only kidnapped the young woman, and perhaps not for himself, possibly for John of Gaunt. Stimulating stuff for a country boy like me or Al Purdy – wouldn’t have missed a word of it. In a 1969 letter to Purdy, however, Birney remembers: “I think he got firstclass marks from me; but he scarcely ever attended my lectures” (213).

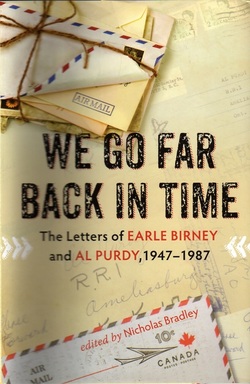

Purdy writes three letters to Birney in 1947, while trying to get poems accepted by him for the Canadian Poetry Magazine, which Birney was editing, and begins a more personal correspondence in 1955, with letters that editor Nicholas Bradley here terms both “pugnacious” and “sycophantic” (15). Much to his credit, Birney replies, with patience and good humour. The two poets’ correspondence continues until Birney’s devastating heart attack of 1987.

Bradley describes his aims in this collection as “primarily curatorial” (30). He has seemingly reproduced all currently available letters exchanged by the two, deleting only brief passages “that seem to me gratuitously offensive, tactless, or cruel about people who are not public figures” and a “few” that disclose “sensitive medical information about” Purdy’s wife, Eurithe (32). He notes that there are frequent gaps in the correspondence where letters appear to be missing – possibly lost, or not yet catalogued, or contained within the numerous cartons of Birney papers still under embargo. Birney was notoriously protective of his public reputation, and within his lifetime prevented researchers from accessing any materials associated with his first wife, the teenage Trotskyist Sylvia Johnstone, or lovers such as

RSS Feed

RSS Feed