While traveling in Europe this summer I was able to see the Tate Britain exhibition “Conceptual Art in Britain 1964-1969,” curated by Andrew Wilson. His understanding of conceptual art is that it is an art that emphasizes process, “overturning definitions of artworks as material, measured by rigid volume and enclosed space, favouring instead measurements of time and duration of that which was open and fluid” (9). Many of the exhibits he offers are documentations, sometimes photographic, sometimes statistical, of artistic action. One of the first items in the exhibit is Richard Long’s Line Made by Walking (1967), a photograph of a field in which Long has walked back and forth until light reflecting from the trodden grass shows the effects of his intervention. His handwriting on the photo’s lower border of the title and “England 1967” adds another form of documentation.

There are a number of “walks” in the exhibition, including Hamish Fulton’s Hitchhiking Times from London to Andorra and from Andorra to London 9-15 April 1967, Long’s Dartmoor Walks (1972) documented with sketches and photos, and his Cern Abbas Walks (1975) which he documents with a map, photos, and a list of observations. These are remote forerunners of later “walk”-structured works, such as Lisa Robertson’s Occasional Work and Seven Walks from the Office for Soft

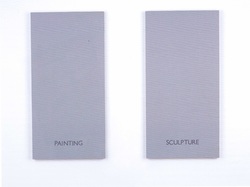

Terry Atkinson and Michael Baldwin, PAINTING / SCULPTURE, 1966-67, Alkyd paint on masonite.

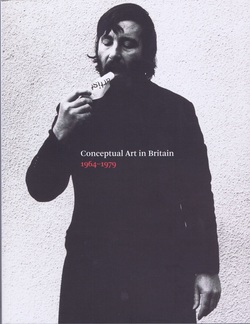

Terry Atkinson and Michael Baldwin, PAINTING / SCULPTURE, 1966-67, Alkyd paint on masonite. Although there are a number of other engaging painterly works in the show, including Keith Arnatt’s Art as an Act of Retraction (1971), a photomontage of the artist eating small pieces of paper with one of his ‘own words’ written on each (an image from this work appears on the catalogue cover), Terry Atkinson and Michael Baldwin’s Map Not to Indicate (1967), a map of North America with every province and state erased except for Iowa and Kentucky, and Victor Burgin’s Possession (1976), a work verbally re-situating a then well-known British advertising image, it was alphabetic works that most interested me. There were not a lot of these. None of the British concrete poets who exhibited in the 1965 Institute of Contemporary Arts show, “Between Poetry and Painting,” which Louisa Lee’s appendix lists as the world’s first exhibition of conceptual art – John Furnival, Bob Cobbing, Dom Sylvester Houedard – are included here. The curator’s emphasis falls on artists who were substituting words both for visual images and discrete art-objects, not on poets who were making words and letters signify both configurationally and semantically. The artist here who perhaps most interestingly combined word and image is Susan Hiller, who in Dedicated to the Unknown Artists (1972-6), elaborately documented her collecting of an early 20th-century postcard series depicting British coastal storms.

One effect of this exhibition for a Canadian is to allow one to understand just how advanced the early work of Greg Curnoe was in terms of the slowly developing global currents of conceptual art – for example, when creating his Row of Words on My Mind (stamp-pad ink on paper, 1962), List of Names of Boys I Grew Up With (stamp-pad ink, ballpoint pen, and graphite on paper, 1962), I hadn’t Even Considered a Typewriter (watercolour, collage, and gouache on paper, 1963), or 24 Hourly Notes (stamp-pad ink and acrylic on galvanized iron, 1966). Curnoe was drawing, stamping and painting words in the place of images throughout these years. Later he would be stamping and painting single words as self-portraits, and throughout scribbling words onto his paintings that recorded what music he was listening to or who was visiting his studio – in effect tracking time’s place. As US critic John Noel Chandler observed in 1973, Curnoe was “doing conceptual art and process art since before these terms were coined”.

FD

RSS Feed

RSS Feed