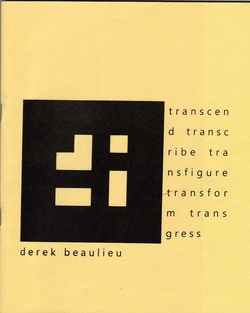

“Kern is made by hand using dry transfer lettering without the use of computers,” Derek Beaulieu begins his “Author’s Note” afterword to this impressive collection of visual poems. Most poems are made by hand, of course, even those made by hands on typewriter or computer keyboards. It’s not so much the hand, however, that Beaulieu seems concerned with here – disabled artists are known to draw with their feet or mouths, and hands are still used to turn on most smartphones and other computers – as it is the non-use of computers. Beaulieu follows the avant-garde tradition here of re-purposing commercial technologies that were abandoned before their full artistic potential could be explored. Usually artists have been attracted to commerce’s cast off technologies such as the letter press and the mimeograph because they’ve been inexpensive to acquire. That’s not necessarily the case here. In fact the production of Les Figues’ elegant 8" x 8" edition of Beaulieu’s poems appears unsurprisingly indebted to computers, right down the barcode.

The most widely known brand name of dry transfer lettering during the 1960s and 70s was Letraset, which bpNichol used in some of his early Ganglia books, and which I used on each page of the first four issues of Open Letter in 1965-1967. Beaulieu writes here that it was then “a specialized tool with an expensive price tag”; I don’t recall that. It was an inexpensive tool by contrast to typesetting, and could be easily combined with the other then developing technologies of offset printing, which I used, and xeroxing, which Nichol used, to make multiple

RSS Feed

RSS Feed