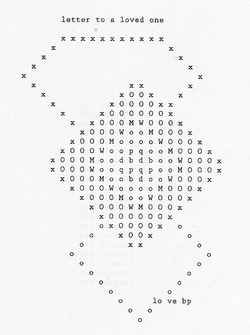

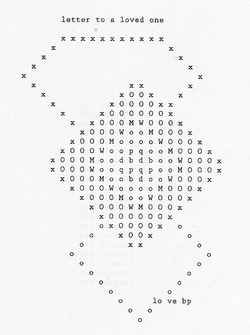

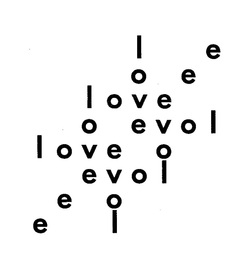

bpNichol, “Letter to a Loved One,” 1967.

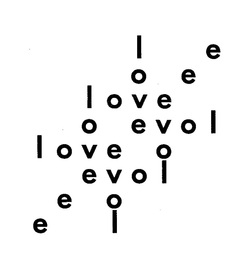

bpNichol, “Letter to a Loved One,” 1967.  bpNichol, “Blues,” 1967.

bpNichol, “Blues,” 1967.

(sections 4-20 via "Read More" below)

|

This is the text and accompanying images of a presentation I gave last night at the RSC meetings in Quebec City. -- FD  bpNichol, “Letter to a Loved One,” 1967. bpNichol, “Letter to a Loved One,” 1967. 1. In my recent biography of Canadian poet and lay psychotherapist bpNichol I outlined the arguments he developed around 1964 for writing visual poems. Unaware of the international concrete poem movement, he was calling his proposed new poems “ideopomes.”  bpNichol, “Blues,” 1967. bpNichol, “Blues,” 1967. 2. These “ideopomes” would help him, he believed, avoid didacticism and self-pitying emotional expression, which he saw as the main weaknesses of his conventional poetry. He also believed that self-pity and narcissism were serious limits on the Freudian psychotherapy he was undergoing, and limits to the success of any psychoanalysis.  3. He would later call his visual poetry a means of resisting “arrogance.” In these arguments one can perceive the shadow of high modernist arguments against Victorian moralism and sentimentality, and in favor of imagism and impersonality; collage and “objective correlative” in early Eliot, and of Pound’s “ideogrammic method.” (sections 4-20 via "Read More" below)

0 Comments

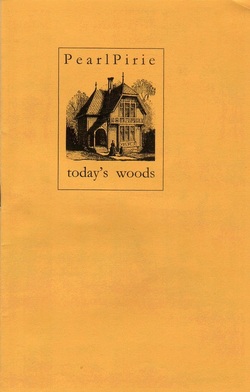

Today’s Woods, by Pearl Pirie. Ottawa: above/ground press, 2014. 6 pp. This very small chapbook came in the mail yesterday along with several other subscription items from rob mclennan’s also small but many-windowed publishing emporium. Once past the cryptic title, this one is more than worth the price of subscription. The long lines of Today’s Woods retell the story of the Three Bears’ apocryphal encounter with Goldilocks – including several non-Goldilocks versions that preceded the 1918 one that turned out to be “just right.” And Pirie’s lines are long – editor mclennan works hard to confine them to their pages, reducing all four margins, and in one case running a line across the gutter onto the adjacent page. So there's a lot of words for only 4 pages. The retelling filters the familiar Eurobear story through the “woods” of both current cultural politics and the physical and behavioral attributes of Canadian grizzly bears. Who cooked the porridge, she asks – was it mom or dad? – which do the details of the story imply? Why did the bears go for a walk and allow their bowls of porridge to reach their varying temperatures? Would bears so skillful as to be able to cook porridge be unwise enough to let it cool? Why is each bear “oblivious to all but own distress. no apparent care about tampering with child’s objects, only each to self, my chair! my bed!”? Is Goldilocks a runaway? Does her occupation of baby-grrrl bear's bed constitute a symbolic sexual assault? Is she a colonial home-invader in a house of indigenous non-white bears? “side note: these are not polar bears in cultural transference to Canada. culturally coded against dark-toned dark-haired bears to be threatening.” The bear parents use the incident to teach their daughter that “she must be self-reliant because humans are running feral”. Like a reality-TV star, Goldilocks labours to believe her own implausible excuses. “Goldy went to therapy to talk about” taking “refuge in good conscience in what she thought / was an abandoned cottage, / despite the fresh cooking scent / and fresh bouquets on table”. But Goldy cannot get out of the woods in this skillfully and amusingly critical parable -- because those woods were darker and more complicated even back in 1918 than we readers first noted. Dark and complicated woods, which in Pirie's interrogative narrative become fresh woods too. On the last page of the chapbook is a note that Pirie has a larger book coming from Toronto’s BookThug next spring. Could be interesting. FD  Stone Mattress: Nine Tales, by Margaret Atwood. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 2014. 280 pp. $29.95. Authors can subtitle their books however their editors permit. Whether or not we readers must accept the “tales” category to which Margaret Atwood has assigned this collection, however, is probably covered by the intentional fallacy. That she wants this collection of a short trilogy and 6 other fictions to be read as tales is clear enough (in beginning her “Acknowledgments” [271] she makes that ‘ask’ lengthily explicit). But the fictions here resemble a number of genres, from the folk tale to realistic short story, genre fiction, and speculative fiction. Moreover, the strong resemblance of all “nine tales” to Atwood’s earlier novels and story collections suggest that she could equally declare those too to be “tales” of varying lengths. “Cautionary tales” perhaps. Aspiring critics of the kind twice satirized in this collection may some day want to explore that. On the other hand, possibly Atwood’s insistence that these are “tales” rather than stories “about what we usually agree to call ‘real life’” (271) is designed merely to protect her from biographical interpretation, or threats of legal action from acquaintances who imagine they see themselves here. Many of the stories are indeed set in Toronto times and places with which Atwood is known to be familiar. She has also inserted a more obvious attempt at legal protection on the collection’s copyright page, one aimed at recent scandalous interpretations of Canadian copyright law: “This is a collection of individual works, not a unified text. “Fair Use” is not a license to reproduce whole stories without permission of the copyright holder.” I wish her luck in defending that. Subtitle and “not a unified text” claims aside, readers of my generation who enjoy reading representations, however unromantic, of the culture of their adolescence should like this book, as should fans of early Atwood. She returns |

Categories

All

Archives

January 2022

|