|

0 Comments

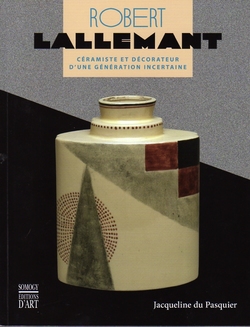

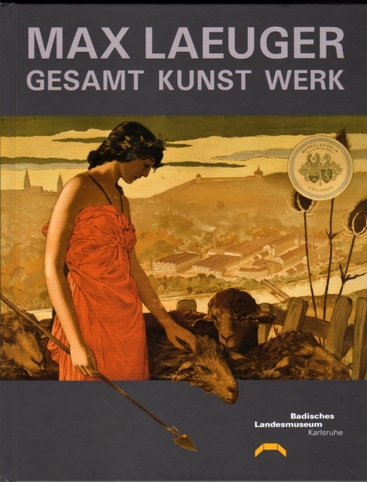

Robert Lallemant: Céramiste et Décorateur d’une Génération Incertaine, by Jacqueline du Pasquier. Paris: Somogy, 2014. 152 pp. 32 Euros. This is the first extended study of the work of the revolutionary French Art Deco ceramicist Robert Lallemant (1902-1954), who flourished in Paris between 1925 and 1933 before mostly abandoning ceramics for furniture design, interior decorating, architecture, travel and photography. Lallemant has been somewhat overlooked by French art history, partly because he was a successful artist-businessman, and partly also because of the brevity of his career, the originality of his designs, and his friendship with Maréchal Philippe Pétain, ‘Head of State’ of the collaborationist Vichy government during the Second World War. Du Pasquier, who has published numerous books on French art ceramics and glassware, particularly those of the Bordeaux region, devotes almost a third of the book to Lallemant’s two years – 1943-44 – as “Special adviser to the civil office of the Head of the State” or “Artistic Advisor to the Maréchal” – ostensibly to show the non-political nature of his devotion to the aging general. Lallemant’s sister-in-law, Aline Montcocol, was the wife of Pétain’s close friend and personal physician, Bernard Ménétrel, who became his chief of staff during the Vichy period. After the war Pétain was convicted of treason, sentenced to death, and died in prison in 1951, age 95, having had his sentence commuted. Ménétrel was also tried but released in disgrace with the case against him declared unproven, and died shortly after in an automobile crash. His widow subsequently became president of a controversial ultra-nationalist association ("L'Association pour défendre la mémoire du maréchal Pétain" or "ADMP") founded to rehabilitate Pétain’s memory. Lallemant himself, who had joined the French navy when war was declared, had moved his wife and children to the relative security of  Max Laeuger: Gesamt Kunst Werk, ed. Arthur Mehlstäubler. Karlsruhe: Badisches Landesmuseum, 2014. 312 pp. 27.4 x 21.4 cm. EUR 24.90. Max Laeuger: Gesamt Kunst Werk is the catalogue for the recently opened exhibition in Baden-Wurtemburg, Germany, that addresses ‘all’ the artwork of Max Laeuger, architecture, interior design, watercolours, sculpture, and ceramics. On the cover the editor has placed one of Laeuger’s earliest works, an advertising poster he produced for a woolen manufacturer in 1894. Here the young Laeuger’s portrayal of wool from Classical sheep to modern mill has inadvertently also symbolized the aesthetic poles of his own career: in the foreground an Art Nouveau idealization of the pastoral; in the background the geometric factory buildings which would not only serve two World Wars but help inspire Constructivism, the Bauhaus, Futurism and Cubism, as well as the functional architecture of concentration camps. It’s an appropriate cover for a book that portrays Laeuger, in the words of the concluding essay, as “an artist between the epochs, a pedagogue in contradiction” (283). I first noticed Max Laueger’s artwork only a few years ago when I encountered an unusual vase (below, left) at a London, Ontario, estate auction. It was 9" high and 9" across its waist, mid-green with a unusually regular, almost geometric, network of black shapes in an overlaid glaze all around it. It was too geometric and abstract to be Art Nouveau but perhaps not sufficiently to be Art Deco. The auction house knew it was a Laeuger, and I further tracked it to his Kandern workshop, in the state of Baden-Württemberg in southwestern Germany, around 1908. So it was contemporary with the painters of Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter, and with the early canvasses of Picasso and the Delaunays. That seemed to make sense. I soon discovered that Laeuger had been born in 1864 during the German equivalent of the Victorian period, produced his first works in 1884-1900 while the Pre-Raphaelites, Art Nouveau and, in Germany, Jugendstil were flourishing, and then had become a respected contemporary of successive waves of modernism including German Expressionism and the Bauhaus, with numerous international exhibitions including a gold medal at the Paris Exhibition in 1925.  A little later I looked into Lauger’s early ceramic work, and sure enough it included small sculptures of ethereal women, often Madonnas, and Art Nouveau vases depicting realistic flowers and flowering plants (below left), not all that dissimilar from what the Moorcroft factory is still producing. But his sculptures, watercolours, and wall plaques of women had become less idealized by the 1920s and in style begun to resemble the rough outlines of figures in the 1906-1920 paintings of Kirchner, Nolde and Schmitt-Rottluff. And as early as 1907-8 his floral ceramics had begun to present highly abstracted shapes such as on this tulip-decorated vase (below right), one example of which is held by Cleveland's Museum of Art. |

Categories

All

Archives

January 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed