A Story of Canadian Art: As Told by the Hart House Collection, ed. Barbara Fischer. Toronto: Justina M. Barnicke Gallery, 2014. 124 pp. $32.00.

A Story of Canadian Art is the catalogue that accompanies the currently touring exhibition of the same name, to be hosted next by the Kelowna Art Gallery (May 2 - July 4, 2015) and the Agnes Etherington Art Centre in Kingston (August 15-November 29, 2015). It presents 41 paintings from the permanent collection assembled by the faculty, students, and artist-advisors of the University of Toronto’s Hart House between 1920 and 1950 and now usually stored at Hart House’s relatively new Justina M. Barnicke Galley. The catalogue is in a small format (9.8" x 6.7") but well printed, with 45 colour plates, and is much more an art book than an exhibition guide.

Its editor and her four assistants who write the one-page commentaries on the paintings rightly insist that this is indeed “a” story of Canadian art – a regional Toronto-centered story among many other possible stories. But this is of course also a story that has enjoyed some privileges. Hart House was a gift to the university by Vincent Massey, heir to the Massey-Ferguson and Massey-Harris farm implement fortunes, and eventual Governor-General and chair of the 1949-51 Massey Commission on the national development of the arts, letters and sciences in Canada. Massey endowed Hart House with funds to make annual purchases of paintings, gifted some, and influenced the principles that guided acquisitions. He was also an early patron of the Group of Seven, and through the Massey-Harris connection a friend of painter Lawren Harris. Not surprisingly 18 of the impressive 41 works in the exhibition are by members of the Group, and another 12 by artists who were Ontario-based.

One fascinating alternative story here is what non-Ontario artists during this period were known in Toronto. Emily Carr, William Percy Weston, E.J. Hughes, and B.C. Binning are the

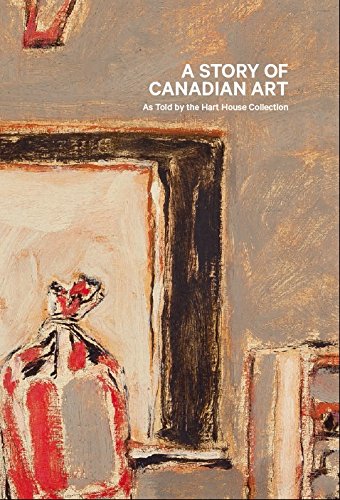

Two of the commentary writers give hints of uneasiness with the dominance of the collection by Group of Seven members. John Geoghegan in his note on the Fitzgerald painting writes of a “a limiting provincialism” in the Group’s “concept of Canadian identity,” and points out how Fitzgerald’s inclusion of “direct reference to human interaction with nature” is a departure from much Group of Seven practice (72). Elizabeth Went writes that Hart House’s 1943 acquisition of A.J. Casson’s 1935 landscape “Autumn Evening” “demonstrates something of wartime escapism, or at least a return to the outdoors ethos that had permeated the relatively stable 1920s” (100). She also writes of Charles Comfort’s 1932 “Young Canadian,” with its powerful suggestion of Depression-era unemployment, that it is “no doubt one of the most significant acquisitions by the [Hart House] Art Committee” (82). At the same time all the writers, along with Barnicke curator Christine Boyanoski, who contributes an opening essay, make positive note of the international recognition which the Group brought to themselves and Canadian art. On the catalogue's cover, however, the editor features a work not by a Group of Seven member but one by their equally experimental Ontario contemporary David Milne – his 1935 “Still Life with Windbreaker and Red Bag.” This may be the first still life anywhere to depict a windbreaker. With the two personal objects it and entirely man-made indoor setting, it is also much more intimately social than almost any Group of Seven work. In his commentary on the painting, Geoghegan observes that the window that is visible behind the bag “offers no glimpse of the landscape that lies just beyond” (110).

FD

RSS Feed

RSS Feed