This fourth issue of the online journal Amodern should be of particular interest to the local people on the London Open Mic site. Most of the issue's articles reconsider the poetry reading series as a place to distribute and bring attention to new poetry. It is guest-edited by Jason Camlot, lead investigator of Concordia University’s SpokenWeb project, and media archaeologist Christine Mitchell.

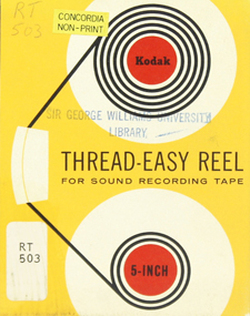

Camlot’s Spoken Web project has been examining, in his words, “digitized live recordings of a Montreal [Sir George Williams University] poetry reading series from 1966-1974 featuring performances by major North American poets, among them Beat poets, Black Mountain poets and members of TISH, a Canadian poetry collective[;]" his "team is investigating the features that will be the most conducive to scholarly engagement with recorded poetry recitation and performance.” Much of this Amodern issue concerns that research, while other articles address contrasts between the role of the public poetry reading series in the 1960s and its function today.

Al Filreis contributes the essay “Notes on Paraphonotextuality” – a useful and accessible essay, despite its potentially daunting title, on the extras that a poetry reading can add to the printed text. Using US tape-recorded readings, he looks at the role of audience reactions in changing a poet’s way of presenting the poems, the effects of different kinds of audiences – friendly,

Marjorie Perloff’s contribution (written as an afterword to the others) however maintains the formal/performance distinction by positing that there are “two groups of poets – the performers, who must be heard as well as read, and the “writerly” poets whose readings are ancillary to their texts rather than wholly integral.” As those familiar with Perloff’s criticism will know, she has been interested primarily in non-writerly poets for whom the paratextual as theorized by Filreis has been at least as much of a poetic element as has the textual. Here she suggests -- not surprisingly -- that “The most necessary Poetry Series, then, would be one featuring performative poetry.”

Perloff also notes that the digital recovery of 20th-century tape recordings of poetry readings has been accompanied both by a proliferation of people who wish to be considered poets and by a sharp decline in the readers of poetry. She wonders whether the poetry reading series, including its now open-mike component, has morphed from a literary to a social event in which much of what is presented is “just ordinary prose, perhaps lineated, perhaps not. [....] [T]he endless clichés, banalities, vapid sentiments, and well-worn ideas expressed [make] one long for access to the internet, where a click or two could provide more interesting, informational, provocative, and distinctive discourse.” She notes an absence of questions of value in most of the other contributions to this Amodern issue – that they discuss mostly the technical aspects of the digital archiving of old tapes and the scholarly questions that have arisen from it, while meanwhile the university study of poetry continues to diminish. “The information industry is so far ahead of the acquisition of knowledge and critical judgment that ‘poetry’ is rapidly becoming something one does rather than something one could know." Thus more people eager to read their own poetry than to read that of others.

Among the other important contributions are Cameron Anstee’s “Setting Widespread Precedent: The Canada Council for the Arts and the Funding of Poetry Readings in Canada (1957–1977),” Christine Mitchell’s “Again the Air Conditioners,” an essay on the decidedly non-literary institutional apparatus that created the SGWU recordings, and Deanna Fong’s “Spoken, Word: Audio-Textual Relations in UbuWeb, PennSound and SpokenWeb,” an essay in which she suggests ways in which other digital collections of tape-recorded poetry could be designed and constructed.

Brian Reed’s “Somewhere Bluebirds Fly: Jackson Mac Low Directs a Poetry Reading” uses Mac Low's SGWU reading/performance to develop an overall assessment of Mac Low's career accomplishments. Many interesting perceptions here, though somewhat marred his series of sarcastic ‘bluebird’ subtitles aimed mostly at the irony he alleges is created when chance operations are ‘directed.’ It is a paradox of aleatory art that it usually does requires choice, self-discipline and management to allow it to happen. Bowering’s aleatory long poem Genève, for example, is also a procedural poem. Reed, however, appears to find the procedures by which Mac Low enables the unscripted to happen in his performed poems contradictory and at times offensive -- though clearly he shares much of Mac Low's dismay at US cultural politics.

Gregory Betts’ “We Stopped at Nothing: Finding Nothing in the Avant-Garde Archive” has only a slender connection to the topic of the issue, and indeed "nothing" to say about readings or reading series themselves as presentation genres. He focuses instead on the fictional 1963 ‘Vancouver Poetry Conference’ (a name and concept created a decade after the 1963 events) and invents a “bifurcation” between the poets of the New American Poetry and Tish newsletter who were, he suggests, “heavily invested in the value of the human self” and the “collagist” poets of downtown Vancouver, but like Reid stumbles over the aleatory by not noticing how it dissolves both his attempted bifurcation and attempted characterization of his New American Poets as individualists (cf. Olson’s “composition by field” and Duncan and Spicer’s serial poems).

I should add that Amodern overall is a venture worth tracking – “a peer-reviewed, open-access scholarly journal devoted to the study of media, culture, and poetics” with contents licensed for use under Creative Commons. Its general editors are Scott Pound of Lakehead University and Darren Wershler of Concordia, and its focus to date North American. Its first issue was appropriately “The Future of the Scholarly Journal,” its second “Network Archaeology” (something for a website like London Open Mic to think about), and the third “Sport and Visual Culture.” Some of its best offerings have been its interviews such as Pound’s of Jerome McGann in the first issue.

FD

RSS Feed

RSS Feed