This latest poetry book from Bowering is a loosely assembled gathering of his recent writing, including half a dozen prose sketches and two or three series that appear undertaken to pass the time while travelling. As he writes in the book’s opening section about the unexpected visits made by Death, “So we fill our days / or allow them to fill / with inconsequence, not exactly planning / to continue till / to our surprise / the fellow is here” (17). But Bowering too can surprise, with his poems, even if filling his days.

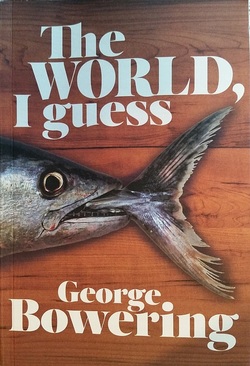

It’s that opening section, one that is mostly about living in years in which “the fellow” Death often calls, that makes this book worth buying – at least it does for this reader who is close to those years himself. The poems here are especially disturbing because they come from a writer who for so long has seemed athletic and indestructible. But, as the cover image suggests, we live for a while only because others die, and eventually those others include ourselves, poor fish.

The second interesting aspect of this section, and of the poems throughout, is how much they are reminiscent of Louis Dudek’s final poem project, Continuation – similar random observations about "the world," similar reflections on humanity then and now, similar affirmations of the persistence of poetry despite changing times. Well, they were written at similar (st)ages.

The concluding section of the book, although a time-passing cruise ship exercise, is also strong. Bowering had taken a college anthology of Canadian literature with him on this cruise, and

Get the poet upstairs however you can,

push on the seat of his pants if necessary,

peel his fingers away from his pen

then frisk him for other writing utensils,

check out his shoes and his coat

lapel

tell him it’s time to take a rest, five

poems a day about every stray cat

and lame dog are too many for any poet

or reader,

.... (133)

I wasn’t especially engaged by two other sequences of apparent travel exercises, “Los Pájaros de Tenacatita,” written in a verse form Bowering reports having learned from Cuban-American poet Pablo Medina, nor by “La Manzanilla Quatrains,” brief observations that recall another (and more interesting) Dudek-alluding poem, Sitting in Mexico. But, having helped fill time, these sequences also help fill a book. I was engaged however by another long section, “The Flood,” that recalls the observant and creatively distractible Dudek of Atlantis and Continuation at his best. Setting bizarre and irredeemable events in the present against the apparent objectives of a once earth-cleansing Yahweh, Bowering is both more witty and formally daring than Dudek. Poesis reveals the irredeemable for our understanding, Bowering suggests, even if it is unable, like Yahweh, to expunge it. “Poetry ... / will tell us / most of what we need to know / we don’t know yet.” He ends here with Dudek’s ocean metaphor. What we don’t know (or perhaps don’t want to know) is “beyond the ocean / where nothing is / and awaits us” (102). It’s a spectacular poem partly (and thematically) disguised as a prose poem, of which no review can give more than a glimpse.

Bowering punctuates the collection with six prose narratives from his early years, “Inside the Tent,” “The Swimming Hole,” “Auntie Pam,” “Somebody’s Horse,” “The Giant Snowball,” and “Air Camera,” about moments “that took me past the boundary line of comfort into a psyche-region that required not so much words as a realization that something like organized alarm was called for” – i.e. poetry. He suggests that within each of these moments were intimations that he would become one of poetry's writers. These are curious texts both as theories of poetry and self-explanations. Several of the uncomfortable moments have been part of Bowering’s writings already – their elaboration here will likely trigger some day critical comparisons. It also works to make the book a sort of career summary, a suitable book on which to end things by creating end things. Dudek did that several times, creating several continuations of Continuations. I expect Bowering may do similarly. Some poets, fortunately, find it hard to stop for death, as well as hard to stop thinking of it.

In the book's title poem, he considers unrecorded poems and their "poor mute Miltons," and writes "even if you write it down, here's the problem, you will be / miswriting, because you are misreading. You have to accept that / if you want to spend a life at this job" (1). Misreading one's own death as imminent, however, has its advantages, especially poetic ones.

FD

RSS Feed

RSS Feed