This is a passionately written academic book – a characterization which the author would probably agree should not be an oxymoron. The passion suggests that it is written as much for curious general readers as for academics. I hope it reaches many of both, particularly those who know or have known war survivors. The $49.95 list price is a bit misleading – some bookstores are currently selling the book for as low as $33.00.

Sherrill Grace’s title, Landscapes of War and Memory, which adapts the “landscapes of memory” theories of psychologist Laurence Kirmayer, foregrounds her basic thesis that the representations of modern war most widely circulated in Canada have been marked by two contradictory cultural imperatives: one, both official and populist, to forget, unconsciously repress, or consciously suppress “shameful past events,” and a second more humanistic one to collectively remember and speak about such distressing matters in “disruptive [but presumably healing] narratives of revelation and disclosure” (58). By forgetting, by not remembering, she writes, Canadians betray those who suffered and died on their behalf – “by ... forgetting the stench of reality, the lies about honour and sacrifice, the greed for military might and wealth, the fathers’ betrayals of their sons” (121).

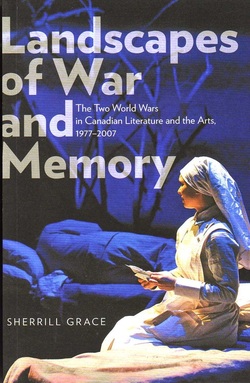

Grace’s specific subjects are Canadian literary and visual representations of 20th-century war created in the 1977-2007 period, and the tasks of collective national memory that these perform. She chooses 1977 as her beginning because Timothy Findley’ novel The Wars and play Can You See Me Yet and Heather Robinson’s art book A Terrible Beauty: The Art of Canada at War were all published that year. Her acknowledgment of the latter allows her to discuss at length several paintings done by official Canadian war artists during the World Wars despite the fact that they were done some 30-50 years before 1977. This asynchrony – Canadian visual art from 1915 to 2007 compared with literary work from 1977 – is slightly odd, although it doesn’t really affect the strength of Grace’s arguments since the visual art works she builds them on are mostly post-1977 documentary film productions. (Post-1977 Canadian painters, unlike

RSS Feed

RSS Feed