This is a journal issue that celebrates not the publisher Coach House Press that went bankrupt in 1996 but the Coach House printing business that still operates under its founder Stan Bevington. Each copy comes with a loose print of a photo that Bevington took of the small workroom that was the Coach House printshop for its first two years.

The issue begins with a reprint of Dennis Reid’s “The Old Coach House Days,” a short memoir of those years between its founding in November 1964 and its design and printing in late 1967 of bpNichol’s bp, a boxed collection of loose visual poems, a chapbook, a flip book, and a small vinyl recording – together remembered here by Reid by the chapbook’s title, “Journeying and the Returns.” This is followed by a pair of articles by John Maxwell, “The Early ‘Digital’ Period,” on the computerization of Coach House typesetting in the 1970s and 80s, and by printer Tim Inkster, “A Pair of KORDs,” on the evolution of offset printing at the press. Then comes a photo-essay by Sandra Traversy, “A Short Walk around the Perimeter of a Heidelberg KORD,” a

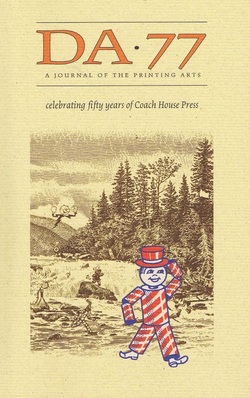

The Devil’s Artisan is, according to its masthead, “A Journal of the Printing Arts.” It is printed and published by Porcupine’s Quill, the press founded and operated by the master printer Tim Inkster – details that its usual readers would likely know. They would know what a Heidelberg KORD was, and quite possibly know about Slocombe’s work in the digitization of the Globe and Mail’s typesetting in the 1970s and about SoftQuad, the pioneering typesetting software company he co-founded, partly at Coach House. The journal’s specialized focus perhaps explains the need to pad the issue with non-Coach House material. But the issue is definitely general-reader-friendly, generously laden with photographs and explanations of historical roles and relationships.

Far from being only a description of a pair of 3-ton offset presses, Inkster’s “A Pair of KORDs” is an illuminating analysis of just how remarkable the spectacularly produced early Coach House titles were considering the limitations of the equipment and materials that Bevington was working with. It’s an analysis only someone intimately familiar with papers, presses, fonts, and inks could offer. Maxwell’s article on the history of the ‘early digital’ period at the press is the most technically detailed narrative of that era in the press’s history that I have encountered, and again provides insights that offer additional ways of reading Coach House’s unique early books. He is especially interested in the pioneering efforts of the press, its being “in the forefront of nearly every significant in publishing technology since the 1960s” (9), its being “[b]y the early 1980s ... the first UNIX-based, network connected publisher” (17). But he does overlook some of the roles played by the press’s editors in that rapid evolution.

Coach House, for example, was in 1979 the first publisher in Canada to offer on-demand copies of some of its books. It was the idea of editor bpNichol, who realized that the newly available line-printer proofs could be quickly bound as unique chapbook objects. More than twelve such titles were listed for sale by the fall of the 1979 as "Coach House Manuscript Editions." Coach House was also first, I believe, in offering its editors remote access to its typesetting facilities. In 1983 my Apple II+ was hardwired through a pale-blue 1200 baud Gandalf modems to the new Coach House UNIX computer, giving me the same 24/7 terminal access that VT100 terminals provided within Coach House itself (the Apple could emulate the VT100) – plus access to the North American UNIX email network. I recall that I paid Bell Canada $6.00 a month for that dedicated data line.

Coach House was possibly also the first to typeset a book from emailed digital copy. The book was Stephen Scobie’s bpNichol: What History Teaches, published in Vancouver by Talonbooks in 1984, in a criticism series that I was editing. Scobie had an early UNIX account at the University of Victoria. He emailed the book to me, chapter by chapter, which I received through that dedicated line between my Toronto house and Coach House. I edited and coded the chapters with SGML and saved them on the Coach House UNIX box. Coach House Printing then produced and mailed the typeset pages to Talonbooks for printing.

A closely related 'first' was Swift Current, the first literary e-magazine in the world, as far as I know, which Fred Wah and myself launched in September 1984, thanks partly to the technical assistance of the Coach House software guru David Slocombe and his company SoftQuad, and to the 1200-baud dedicated data line I enjoyed to the Coach House UNIX system. Coach House Press published our Swift Current Anthology in 1986.

Small omissions aside, this issue of The Devil’s Artisan is an important and useful addition to Canadian literary history. A lot of people may want to get a copy.

FD

RSS Feed

RSS Feed