(This review lightly revised Nov. 2018)

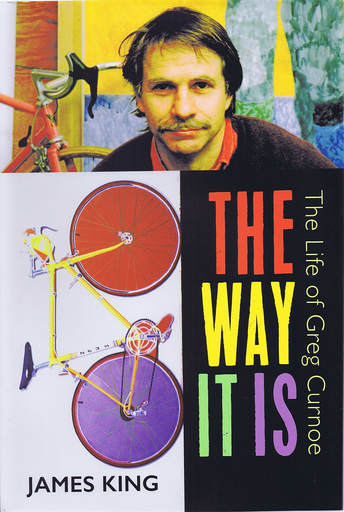

The Way It Is: The Life of Greg Curnoe is a beautifully produced book, printed on heavy high-gloss paper to accommodate more than 70 colour photos of Curnoe’s art – worth its price for those more than for James King's commentary. The images create a parallel biography to the one which King attempts in his text, and to a large extent renders his pedestrian by contrast to its own richness and complexity. King doesn’t discover anything really new or unknown about Curnoe, or attempt to do much original research, but he does assemble much known information that has not previously been together in the same place. As well as a beautiful book, it’s a handy compilation of facts and opinions together with a bibliography of commentary about Curnoe in which the only items missing appear to be two articles of mine from 1995 and 2003 about his lettered work.

King gives the impression that he was fairly thorough in interviewing Curnoe’s family and friends and in researching Curnoe’s critical reception and the notes and journals he left for his archive, held by the Art Gallery of Ontario, but he seldom questions or reflects for long on what he encounters. He tends to accept at face value most of what his interviewees tell him, despite being aware that many speak from backgrounds utterly alien to the assumptions about art and art history that preoccupied Curnoe. Even about non-art matters he can be recklessly presumptuous in his generalizations. For example, he declares early in the book about the noise band in which Curnoe was co-founder and drummer (the Nihilist Spasm Band) that “all the members were men who felt strongly that a woman’s place was to be a helpmate to her spouse or partner” (136). How he or a possible informant – he does not identify a source – could claim to “know” such a thing about eight men – right to the strength of the feelings – is baffling. (In chapter 10 he quotes band member Art Pratten as saying of the group that “Playing in the only thing we have in common. [....] We couldn’t agree on anything, not one damn thing” [216].)

King is presumptuous also about Curnoe, buttressing otherwise unsupported claims about him with the phrase “Greg would have known” (139), or “Greg would have immediately realized,” “Greg would have been aware” (142), Greg would have seen” (151), “Greg would have known

King’s own conception of Curnoe for most the book is of a highly creative and rebellious “bad boy” who is nevertheless paradoxically and nostalgically attached to the illusory security of the bourgeois home. He tells us that his teachers saw him as lazy and unmotivated for being content with 60% grades throughout most of elementary school (39), that he was a “‘handful’ for his parents” (41), and that he disappointed his father by never aspiring to hold down a steady, well-paying job; that his first serious girlfriend “felt his manner was threatening” (59) when she left him for someone else; that he even described himself as having deliberately been, while studying at the Ontario College of Art in 1957-60 , “a shit disturber. I told the teachers what I thought of them. I didn’t like most of them. [...] I was, I suppose, pretty obnoxious” (62). King tells us that London Ontario arts officials such as Clare Bice and Nancy Poole in the following decades saw him as a persistent troublemaker, quoting Poole as saying “I don’t think Greg was as nice as Greg’s fans think he was .... I had no illusions about Greg” (264); and that the Canadian Department of Transport viewed him as a having created “an inflammatory message about American imperialism and violence” (180) when in 1967 he delivered the mural R34 that he had been commissioned to create for the Dorval (now P.E. Trudeau) Airport. King writes, “Greg, for better or for worse, had firmly established himself as the bad boy of the Canadian art world” (185).

King tends to describe these conflicts from the points of view of those who defend established social convention, and seems particularly sympathetic to the views of Curnoe’s father, his wife Sheila, and the similarly exasperated officials at Dorval. Does King like or admire Curnoe? He clearly admires his artistic abilities, beginning his book with the declaration “Greg Curnoe is one of the most talented Canadian artists of the second half of the twentieth century” (21). However, with its “one of” this is clearly a hedged statement, and one that evaluates his potential – his “talent” – while avoiding evaluating his career accomplishments.

Does he like Curnoe? – it’s easy for a reader to conclude that he doesn’t. In his frequent reservations about him King becomes unfair to Sheila Curnoe as well. Almost every time he mentions her it is because she has objected to something Greg has done (122, 129, 138, 163, 215, 241), been “furious” at what he’s done (148, 197), and in one case been “appalled” at his choice of a new home (165). King asserts that she loved him (129), but gives the reader little reason to believe she did. Instead he stresses incidents in which she appears more focused on her own appearance than on Greg’s success. “Sheila ... was furious when the catalogue of the 1969 Sāo Paulo Bienale featured her in an informal sweater in the kitchen” (197). When Greg finds, buys and dons a rich blue workman’s shirt at the Galleries Lafayette in Paris, he quotes her as recalling: “I had to walk through Paris in my Holt Renfrew outfit with Greg looking like a garbage man” (215).

He also mentions several times her unhappiness at having served as a model for some of Curnoe’s most famous works – Spring on the Ridgeway, Homage to Van Dongen II, Amorous Reading. He notes without comment her confusion of modeling for an image which may not resemble oneself, but be merely an appropriate element in a complex of images, with sitting – like the Queen has done – for portraits intended to be representations of oneself. “She did not appreciate being made to appear in an image as she did not appear in real life” (133). She enjoyed being painted, he implies, but did not enjoy serving as a model for the construction of a painted image. Overall, this one-dimensional characterization of Sheila is entertaining, but is not exactly kind to someone who appears to have been of so much help to King’s writing.

Beyond the generous reproductions of Curnoe’s work, the best parts of this book are the earlier chapters that investigate his childhood, adolescence, and work in the 1960s and 70s. (Something I didn't recognize when writing this review in 2017, but know now in the fall of 2018, is that King's narrative of Curnoe's childhood and adolescence is derived to a great extent from an earlier biography of Curnoe, My Brother Greg, published by the artist's sister, Lynda Curnoe, in 2001. King 'borrows' short sentences from her book without acknowledgement, borrows longer ones by substituting a word or changing the word order, again without acknowledgement, throughout approximately 20 pages of his book. He borrows her anecdotes and other memories of Greg without indicating whose they are. When he comments on Greg's gradeschool report cards, he quotes only the nine assessments by teachers previously unearthed and quoted by his sister -- as if he has found them through his own research. A graduate student who did such things in a thesis would risk outright failure.)

In the later chapters King appears to lose control of his project, or perhaps lose interest in it. He repeats earlier references as if forgetting he has already mentioned that material. Many pages of chapter 11, “A Walking Autobiography, 1971-76,” are a hodge-podge of disconnected paragraphs, especially pages 241-47. In chapter 12, “New Beginnings, 1974-1969,” he tells the reader for the third time in the book that Curnoe and fellow London Ontario painter Jack Chambers were “opposite” in personality (263), for the second time that watercolour allowed Curnoe to reveal “when the brush was lifted” (265), and for the second time that Walt Whitman was a patient of London psychologist Richard Maurice Bucke (275).

Like almost all recent Canadian biographers, both popular and academic, King holds to the traditional “essential self” theory of biography, in which the biographer works to discern who the “real” person was and to gather seemingly factual evidence of how this self was consistently expressed from childhood onward. It’s a good approach to take if one is hoping for a large audience, since most people seem to hold “born this way” assumptions about beliefs and values. He writes that “the biographer must tease out – and then separate – the man from his art” (24) as if any person can exist separately from how they have lived, and what they have done. His work here in The Way It Is is untouched by poststructuralist theories of the self as being unconsciously “hailed” by ideologies, as in the work of Louis Althusser, or offered by culture a limited choice of “positions,” as in Pierre Bourdieu’s The Rules of Art and Distinction.

But he seems nevertheless aware of the extent to which Curnoe did perform being the eccentric convention-defying artist, especially in how he dressed and behaved – a role that virtually compelled him to risk flunking out of art school, to have his Dorval mural condemned to dismantling and indefinite storage, and in the 1980s to produce himself as the costumed and variably-tinted cyclist both on the road and in numerous amazing watercolour “self-portraits.” King seems partly aware also of how Curnoe’s 1992 “auto-portrait” series in which he painted himself as the words “Je,” “moi,” “Mi” “niin,” “ME,” etc. reflected his understanding of how the self was multiple and variable, and constructed in both language and cultural practice. He writes “In a very real sense he was allowing the concept of the 'I' of Greg Curnoe to flow into the 'I' or 'me' of the citizens of the First Nations” (331). Curnoe performed these selves to the point of believing utterly that they were him. And they were. And one became irrevocably him when it led him to death. King’s attention to these performances here is admirable even though inconsistent and untheorized.

Overall this a fascinating book, in no small part because King tends to see world so differently from how Curnoe experienced it.

FD

RSS Feed

RSS Feed