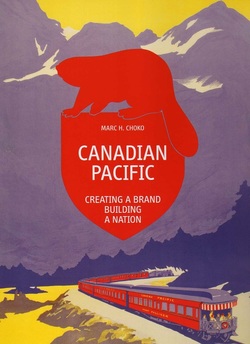

Despite the commercial and political emphases of its subtitle, this is more a nostalgic art book than a nostalgic history text or elaborate advertisement. It comes to market thanks to Matthias Hühne, the evidently wealthy patron-publisher of a press he has founded to preserve and celebrate some of the best of twentieth-century commercial art, especially that produced by the airline industry. So far he has published no more than one book – lavishly produced – a year. Last year it was the spectacular Airline Visual Identity, 1945-1975, which he wrote and edited himself. This year it is Marc Choko’s Canadian Pacific, again with superb colour reproduction values which appear to have cost more than the cover price suggests. Next year it will be the visual self-representations of Pan American Airline, in his own Pan AM: History, Design & Identity. Does the art work commissioned by an airline deserve to be reproduced as faithfully as the Book of Kells or the Duc de Berri's Tres Riches Heures? In these books it is.

The history of the CPR and its hotel, shipping, airline and other enterprises, from the railway’s beginnings in the 1880s to the 1980 end point chosen by Choko and Hühne for this volume, coincides with the flourishing of colour printing in advertising and magazine production – a period that symbolically ends with Kodak’s bankruptcy in 2012 and the rapid 1969-2004 expansion of the internet. CP’s locomotives, steamships, aircraft and the printing presses of its posters and magazine ads were all part of that Benjaminian age of mechanical reproduction

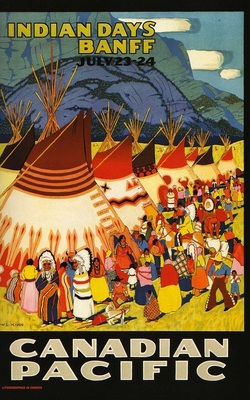

Poster by Wilfred Langdon Kihn, 1926. Choko 177.

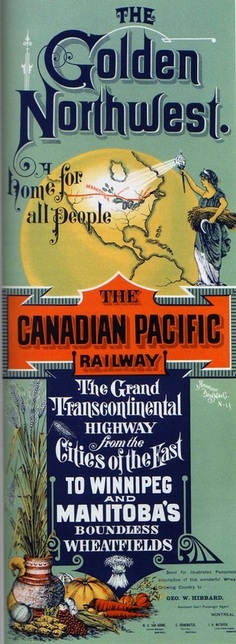

Poster by Wilfred Langdon Kihn, 1926. Choko 177. Only 42 of Canadian Pacific's 384 pages are text; 14 are maps, documentation, and other end matter. Nearly all of the remainder present images, mostly in colour and often full-page. So the book’s discursive rendering of “creating a brand” and “building a nation” is pretty brief and standard. The 1882 completion of a Canadian transcontinental railway forestalls the absorption of British Columbia and the Hudson Bay lands by the U.S. The railway opens those lands to settlement. It facilitates the movement of Canadian troops to quell the 1885 North-West Rebellion. The granting of extensive amounts of land to the railway, land which to its tracks add value and which it then resells, enables the rapid development of cities such as Vancouver and Regina. Creating a brand involves creating new commercial platforms on which to display that brand – hotels, land-sale offices, inland steamships, ocean liners, aircraft – and the rapid change from “Canadian Pacific Railway” to “Canadian Pacific” and toward the logo “CP.” It involves diversifying and modifying its activities as the world economy is roiled by technological change, world wars, and a global depression. These cursory narratives are offered by Choko mainly to give context to the images, which are what both author and editor are most interested in. The legends of how the railway in its first 20 years paid First Nations people to camp in their teepees beside the track, so that passengers could see them, is not here, nor of other massive disruptions the railway helped bring to indigenous culture. But the visual evidence of those is here in the feather-decked faces that smile out from some of the advertising.

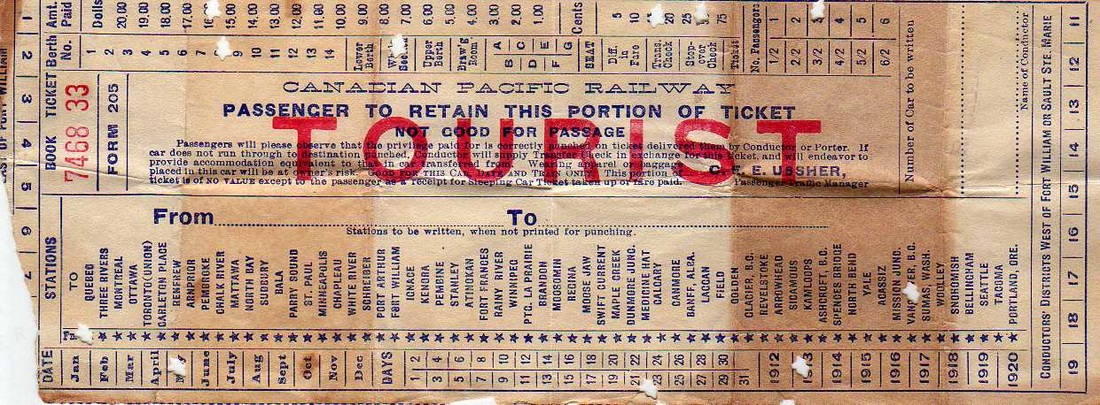

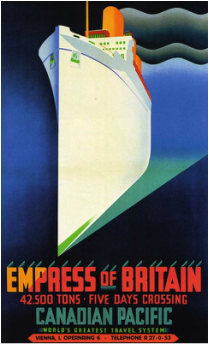

Certainly the CPR played a huge role – too huge, one might think – in shaping the lives of Canada's inhabitants. My own family is an example. My late wife’s grandfather prospered in the 1880s and 90s designing and building houses, a hospital, a school and shops on land in Vancouver that was gaining value by CP’s decision to move its western terminus from Port Moody to Vancouver. In 1893 he was able to take his family to the Chicago World’s Fair, over Canadian Pacific Railway tracks. My paternal grandparents were lured in 1904 to go by rail from Ontario to Vancouver where my grandfather found work with the British Columbia Electric Railway Company – a company that was in 1904-5 just starting out by electrifying a rail line from Vancouver to Steveston originally built by the CPR. My maternal grandparents came immigrant class from Britain in 1913 on CP’s Empress of Ireland and travelled to Vancouver from Quebec City on its railway. They preserved their CPR ticket for the rest of their lives – "passenger to retain this portion of ticket" indeed!

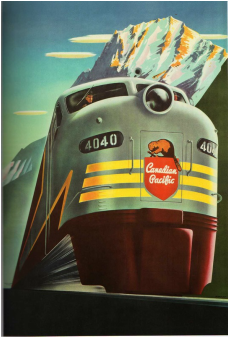

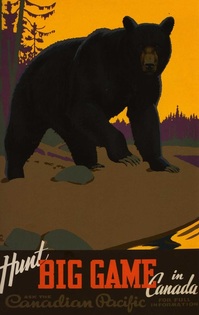

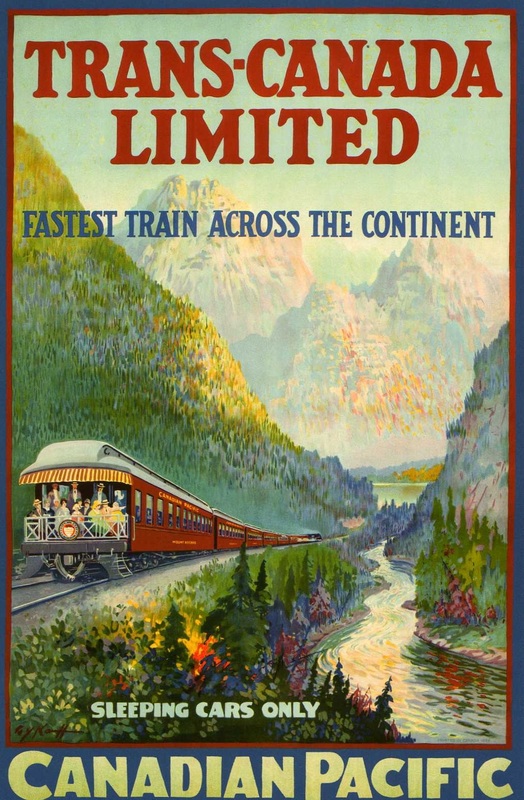

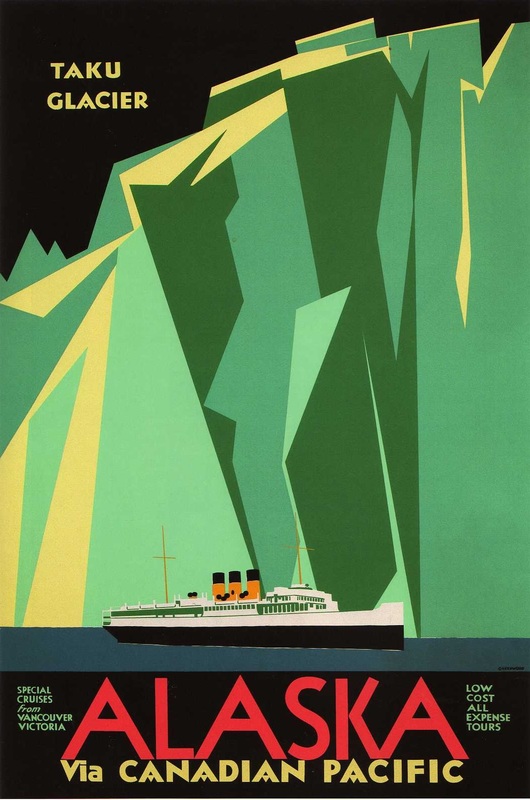

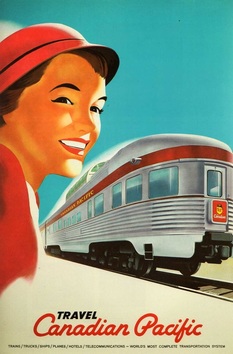

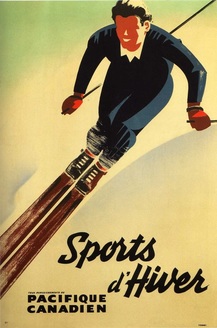

That dominance of CP in early twentieth-century Canada will give this book’s images special meaning to readers who have some connection to that period. One thing many may note is the enormous size CP awards itself in many of them. Its ships are photographed from the waterline upward so that they tower over the viewer, locomotives are similarly photographed from railbed level. They promise to deliver the dwarfed but happy passenger to places where nature is similarly oversize, and similarly imposing. Moose, bear, mountains can tower over the locomotives that previously towered over prospective passengers. The similarity in composition between the images of ships and the images of nature suggests that the company is identifying its properties with the natural, as if it wants to be seen as similarly enduring and powerful. In the images of trout, bear and moose, which of course the railway is presenting as potential trophy-kills, the similarity offers a certain irony.

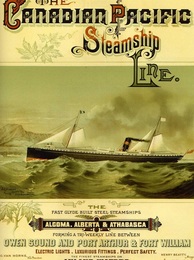

Choko’s comments on the art itself are brief but useful. He points out how belated the style of CP’s art tended to be until the 1930s when CP established in Montreal its own silkscreen studio, a process which favored the flat colours of Art Deco. He remarks that in whatever style, the art necessarily romanticized what it represented, sometimes not merely in smiling faces but in explicit promises, as in the 1884 steamship poster below that promised "perfect safety." Despite the technical accomplishment of the mostly British artists of 1880-1930, their work is largely Victorian and Art Nouveau in these early decades, and not often Impressionist until the 1920s. The work of the mostly Canadian artists of the silkscreen studio remains Art Deco into the 1940s and 50s.

FD

RSS Feed

RSS Feed