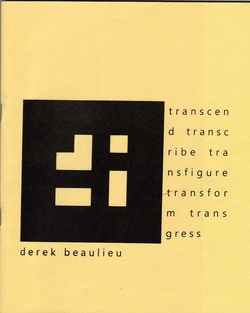

If Derek Beaulieu fans (myself included) have a sense of deja vu as they begin this chapbook-prosepoem-essay-manifesto, it’s because its first page or so expands statements he made in the last pages of his interview by Lori Emerson in his 2013 selected poems, Please, No More Poetry.

Those pages left Beaulieu with a few things to sort out and clarify, particularly the passage

the “golden arches,” the Nike “swoosh” and the Dell logo best represent the

descendants of the modernist poem. Poet Lew Welsh famously wrote the

ubiquitous Raid slogan “Raid kills bugs dead" as a copywriter at Foote Cone

and Belding in 1966. Vanessa Place argues, “we are in an age that understands

corporations are people too and poetry is the stuff of placards. And vice versa."

Like logos for the corporate sponsors of Jorge Luis Borges’ library, my concrete

poems use the particles of language to represent and promote goods and

corporations just out of reach.

Among those things this passage left suspended was the question of whether Beaulieu likes modernist poems. And what poems does he consider modernist? Does he know that the 'famous' story that claims that Lew Welch wrote the Raid 'poem' is undocumented, and at best an urban legend? Should he perhaps, like Margaret Atwood several decades ago, incorporate himself? Has he noticed that the 1942 “Loose lips sink ships,” created by the War Advertisers Council, is a modernist precursor of the Raid poem and like it had a corporate author? Does he think Lew Welch should have stayed in advertising? I am of course pulling Derek’s chain, but I do wish that he had undertaken in that interview to be as careful on some of these points as he has been in creating his artwork.

One change Beaulieu makes to this passage in his new book – seemingly following both Cummings and the once continually revising Earle Birney – is to remove all capital letters and to replace all his punctuation with spaces. Another – perhaps following Charles Olson’s use of large caps – is to use boldface for emphasis, thus overall making his text appear more ‘poetic’ than academic. (So much for “no more poetry,” eh, Derek?) Another is to raise the intensity of

if poetry is going to reclaim even a shred [!] of relevancy for a contemporary audience

then poets must become competitive for your readership and viewership as graphic

design advertising and contemporary design culture expand to redefine and rewrite

how we understand communication poetry has become ruefully [!] ensconced in the

traditional. .... the vast majority of poets are trapped [!] in the 20th (if not the 19th)

century hopelessly [!] reiterating tired tropes mcdonalds golden arches the nike swoosh

and the apple logo best represent the contemporary descendants of the modernist poem

poet lew welch famously wrote raids ubiquitous advertising slogan raid kills bugs dead

as a copywriter at advertising firm foote cone and belding in 1966 los angeles-based

vanessa place argues that

today we are of an age that understands corporations are people too

and poetry is the stuff of placards. or vice versa

the stuff of poetry – craftsmanship and handiwork – as opposed to the industry of

advertising relegates poetry to a role out of touch with the driving economies of the culture

advertisers and graphic designers use the fragments of language to fully realize emotional

social and political means – and in doing so have left poets with only the most rudimentary

tools in doing the same

All manifestos are self-serving – Victor Coleman will have something to say about this at the end of this post. But many effective manifestos conceal that by saying little about the art or artists that they would displace, or by speaking humbly about their own efforts. Tzara in his “Dada Manifesto” writes “I speak only of myself since I do not wish to convince, I have no right to drag others into my river, I oblige no one to follow me and everybody practices his art in his own way.” Borduas in the Refus Global makes no mention of rival art or artists. Wordsworth in his preface to Lyrical Ballads immediately after having condemned his contemporaries for “their frantic novels, sickly and stupid German Tragedies, and deluges of idle and extravagant stories in verse” writes:

When I think upon this degrading thirst after outrageous stimulation, I am almost ashamed

to have spoken of the feeble endeavour made in these volumes to counteract it; and,

reflecting upon the magnitude of the general evil, I should be oppressed with no dishonour-

able melancholy, had I not a deep impression of certain inherent and indestructible qualities

of the human mind, and likewise of certain powers in the great and permanent objects that

act upon it, which are equally inherent and indestructible; and were there not added to this

impression a belief, that the time is approaching when the evil will be systematically opposed,

by men of greater powers, and with far more distinguished success. [Perhaps Wordsworth was

foreseeing Derek Beaulieu.]

Unapologetically telling “the vast majority” of his contemporaries that they are “trapped” and their poems are “hopeless,” as Beaulieu does, is usually not good literary politics – especially when the vagueness of “vast majority” allows all writers who don’t at least hand-draw their poems or work for an ad agency to imagine that they have been included. But Beaulieu may not be addressing as large an audience as Wordsworth was accurately imagining. Much more likely he is performing his manifesto mostly for other conceptual poets, such as the ones he discusses a section of text at time in the following 31 pages, and thus asserting and re-asserting his affiliations with them and their “readership and viewership.” This is a transnational audience from the US, Britain, Norway, Germany, and a couple from Canada, and reflects both the concurrent globalizing and fracturing of literary audiences since Wordsworth’s time, and the changing conditions for audience-address. Those 31 pages, incidentally, are the best parts of the chapbook. There’s lots of information there that some poets, readers, and viewers might want to look further into.

Beaulieu is also good on explaining some of the links between visual and conceptual poetry and on suggesting that visual poetry is conceptual. Of course these links have been visible in Europe since Dada, and in Canada since the early concrete and pataphysical works of bpNichol (although most Nichol readers at the time mistook them as concurrent rather than related productions).

But I have other comments for Derek. I don’t understand where in this text he stands on matters of what he calls on that first page “the stuff of poetry – craftsmanship and handiwork” and whether he was being ironic there. Two pages later he quotes concrete poet Haroldo de Campos, seemingly favourably, as having “posited concrete poetry as a notion of literature not as craftsmanship but [...] as an industrial process where the poem is a prototype rather than the typical handiwork of artistic artistry,” and appears to praise “contemporary concrete poets fiona banner jen bervin and erica baum” for having created works that “trouble the line between craftsmanship handiwork and industry,” and 12 pages later openly praises them for having chosen a “tradition that discards the fallacy of craftsmanship and handiwork as antithetical to industrious poetics.” Did he mean to write “industrial” here rather than “industrious”? Was his earlier word “industry” an unproductive pun? Or is he pulling a fast one on us by appearing to dissolve de Campos’s dichotomy between “craftsmanship” and “industrial process” while not really doing so? It’s pretty clear that he would like to dissolve it (and I’d to see him do that) but can’t quite find a way.

Then there’s Beaulieu’s apparently gratuitous slam of Charles Olson and Robert Creeley for having been “contemporararies with [the visual poets] gomringer the de campos brothers and pignatari” while also using “the typewriter” as “an office machine ... to create and measure the male voice.” Olson and Creeley were also contemporaries with Denise Levertov who used typewriter spacing as much as did Creeley to represent voice. Daphne Marlatt learned partly from all three to use typographic layout to represent voice, in fiction as well as poetry – a voice, like Levertov’s, not often read as “male.” Beaulieu’s slam here appears to be much less one of Olson and Creeley’s masculinism than it is of all non-visual poetry – i.e. how dared anyone create non-visual poetry once Gomringer, Pignatari and the two De Campos boys had created poems otherwise. (And how dare they now that Derek Beaulieu creates poems otherwise?)

As Victor Coleman wrote of bpNichol’s much more tolerant endorsement of visual poetry in 1966, “bpNichol defends Concrete poetry; like the civil servant will defend his job; we don’t want to put all those cats on the welfare payroll out of a job, do we?” (Open Letter 7, Nov 1966: 18).

FD

RSS Feed

RSS Feed