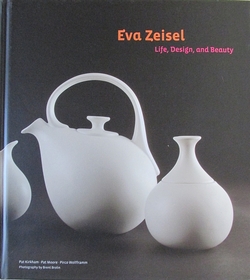

This is an elegantly designed art book, generously illustrated in colour and black and white, including a well researched biography of ceramicist Eva Zeisel, and overall carefully footnoted and indexed. Written for the most part by scholars and collectors who were also friends and colleagues of Zeisel during the last decades of her 73 years in the US, it is also recurrently sentimental, not only about Zeisel’s life and personality but also about aesthetics, often portraying Cubist, Bauhaus, De Stijl, Art Deco and Dadaist art as cold and unengaging, and the curves of postwar American industrial household ceramics adopted by Zeisel when in North America as “organic,” and “humanist,” and as embodying – as the title suggests – “beauty.”

As well, it refers to Zeisel by her first name throughout, subverting the professionalism of some of the contributors and seeming to treat Zeisel less seriously than how her male contemporaries – Max Lauger, Charles Catteau, Jean Luce, Robert Lallemant, Paul Speck, Otto Lindig, Raoul Lachenal – are treated by ceramics scholarship generally. Ironically, the authors also attempt to portray both Zeisel and her mother, Laura Polanyi, who in 1909 earned the first PhD granted to a woman by the University of Budapest, as feminists, because of their ground-breaking efforts on their own behalves. (Is a successfully ambitious woman necessarily a feminist?) Laura Polanyi, however, sister of the noted chemist and philosopher Michael Polanyi and economist Karl Polanyi, and aunt of the Canadian Nobel-Prize-winning chemist John Charles Polanyi (son of Michael and thus first cousin of Zeisel), is indeed a fascinating woman – acquaintance of literary theorist Georg Lukacs, friend of Freud, and apparently a family friend of the left-liberal Hungarian president Count Karolyi who was overthrown by fascists under Admiral Horthy in 1919.

Pat Kirkham’s opening-chapter biography of Zeisel clarifies and enlarges many of the stories that have circulated about her early life. Zeisel, née Stricker, was born in 1906 into an upper-class Austro-Hungarian secular-Jewish Budapest society energized by the changes happening politically and culturally in Europe; its members were variously involved in the arts,

Her first significant work began in 1928 when she moved to Schramberg, Germany, to be the sole designer for Schramberger Majolikafabrik, an industrial-scale dinnerware and household china producer. She left Schramberg in 1930, possibly because unhappy with her name not appearing on her designs, and possibly because she was not enjoying Schramberg’s conservative small town atmosphere. She went to Berlin where her mother had rented for her the studio of Expressionist painter Emil Nolde. Here she did free-lance design work for the Carstens ceramic factory in Hirshau, before in January 1932 seizing a marital opportunity to move to Russia, where she worked for various porcelain manufactories before in 1935 becoming artistic director in Moscow of the massive China and Glass Industry and beginning an affair with NKVD officer. She was arrested and imprisoned in May of 1936, accused of being part of an elaborate and probably fictitious plot to assassinate Stalin, and deported without explanation to Vienna in the fall of 1937. She fled immediately to Britain and made her way with a new husband, law scholar Hans Zeisel, to New York in October of 1938 where she began making the connections with American ceramic design that would lead to the 1946 MOMA exhibition “New Shapes in Modern China Designed by Eva Zeisel.”

For me the best of Zeisel’s designs are the ones she did at Schramberg in 1928-30. Examples of them are hard to find – two years is not long in Schramberger’s history, and her works carry marks similar to those other Schramberger products of the period. Only the numbers embossed on the undersides can confirm which forms are hers, and since these numbers are not widely circulated (though many are published in Kirkham’s book), confused or unscrupulous dealers have been often able to misrepresent non-Zeisel work as hers. As well, little of Zeisel’s work was sold as decorative art, unlike the work of the leading male Art Deco ceramicists. Most were sold as household objects and so had to survive the perils of both the Second World War and regular visits to kitchen sinks.

Schramberger Majolikafabrik also applied her decors to forms designed by others. In my opinion these are also worth collecting, although the authors of this book may not think so. They illustrate only six of her twenty-three Schramberg decors, giving little help to those who might want to identify them. In the book generally, they photograph only Zeisel forms decorated by her or by others, and no non-Zeisel forms bearing her decoration. But the Schramberg liqueur set to the left here (below) decorated in Zeisel’s “Scotland” decor is arguably enhanced by her work. So too is the squat vase beside it in her decor 3526. I would much rather have these examples of her decor – in which pleasure-giving objects must function beneath complexly measured grids of coloured bars and trapezoids – definitely a just proposition in Europe of 1929 – than have none.

It is evident that when Zeisel began work at Schramberg she matched her new decors to the those cubist-inspired ones the company was already using. It had, for example, several spritzdekor decors tiled “Gobelin 2” and “Gobelin 3,” etc., to which she added three more, including “Gobelin 12” (on the tea set below) and “Gobelin 13” ( the cup and saucer below ). But this is how art evolves, building and innovating on current forms, techniques and materials.

It’s in her combinations of design elements that she especially excelled while at Schramberg. One can see in the tea set her combining of offset lid positions, solid D-shaped handles on the lids and cups, and curves joined with straight lines in the handles of the coffee and teapots, creating echoing D's. In the photo below left her pitcher (form 3390) has a spout shape often found in German pitchers of this period, but here balanced by a strikingly circular handle and both joined to a straight-walled barrel with a ribbed surface that she also featured in numerous of her jugs, vases and coffee pots. In the photo beside it the vase (form 3372) is also straight walled but with much wider ribbing and a goblet base. Its “Rustic” decor seems at first glance to have too many elements to avoid appearing cluttered. But it works well, partly because there are only two colours, and only two acute angles in the pattens, and partly because the narrow rows of colour all extend from top to bottom. The complex regularity of the pattern is both simple and a tour de force, and again shows pleasure constrained, clay constrained.

As I wrote when I began, this is a large and elegantly produced book – and also now available at substantial discounts. It offers a fascinating glimpse of European culture between the world wars, and of secular Jewish culture in Hungary before the Holocaust. This is the culture that produced not only the Polanyis but also Georg Lukacs and novelist Arthur Koestler – the latter one of Zeisel’s several lovers. It also unintentionally documents the late-1920s and early-1930s period in which much of modernist art faltered, collapsed or was extinguished – Dada, Bauhaus, Constructivism, and German Expressionism in particular. As for Zeisel, she created outstanding designs throughout her life, no matter what the aesthetic she was working in. All are dramatically represented here.

FD

RSS Feed

RSS Feed