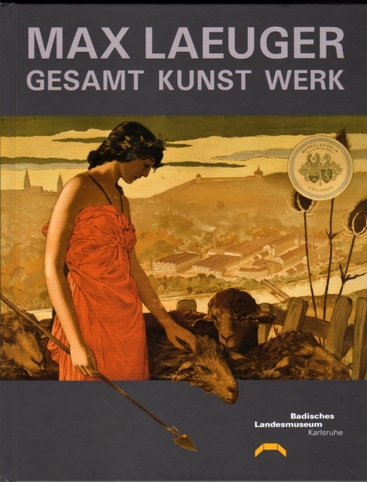

Max Laeuger: Gesamt Kunst Werk is the catalogue for the recently opened exhibition in Baden-Wurtemburg, Germany, that addresses ‘all’ the artwork of Max Laeuger, architecture, interior design, watercolours, sculpture, and ceramics. On the cover the editor has placed one of Laeuger’s earliest works, an advertising poster he produced for a woolen manufacturer in 1894. Here the young Laeuger’s portrayal of wool from Classical sheep to modern mill has inadvertently also symbolized the aesthetic poles of his own career: in the foreground an Art Nouveau idealization of the pastoral; in the background the geometric factory buildings which would not only serve two World Wars but help inspire Constructivism, the Bauhaus, Futurism and Cubism, as well as the functional architecture of concentration camps. It’s an appropriate cover for a book that portrays Laeuger, in the words of the concluding essay, as “an artist between the epochs, a pedagogue in contradiction” (283).

I first noticed Max Laueger’s artwork only a few years ago when I encountered an unusual vase (below, left) at a London, Ontario, estate auction. It was 9" high and 9" across its waist, mid-green with a unusually regular, almost geometric, network of black shapes in an overlaid glaze all around it. It was too geometric and abstract to be Art Nouveau but perhaps not sufficiently to be Art Deco. The auction house knew it was a Laeuger, and I further tracked it to his Kandern workshop, in the state of Baden-Württemberg in southwestern Germany, around 1908. So it was contemporary with the painters of Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter, and with the early canvasses of Picasso and the Delaunays. That seemed to make sense. I soon discovered that Laeuger had been born in 1864 during the German equivalent of the Victorian period, produced his first works in 1884-1900 while the Pre-Raphaelites, Art Nouveau and, in Germany, Jugendstil were flourishing, and then had become a respected contemporary of successive waves of modernism including German Expressionism and the Bauhaus, with numerous international exhibitions including a gold medal at the Paris Exhibition in 1925.

At Karlsruhe Majolika-Manufaktur he produced two lines of ceramics – “Handelswaren” ("merchandise") for work he regarded as routine and industrial, and “Edelsmajolika” ("noble majolica") for work that he painted personally in smaller editions, often with special alkaline glazes. These were also often more modernist in decor, as in this small blue bowl, no. 3015a, an example of which can be seen in the Museum Behnhaus in Lubeck.

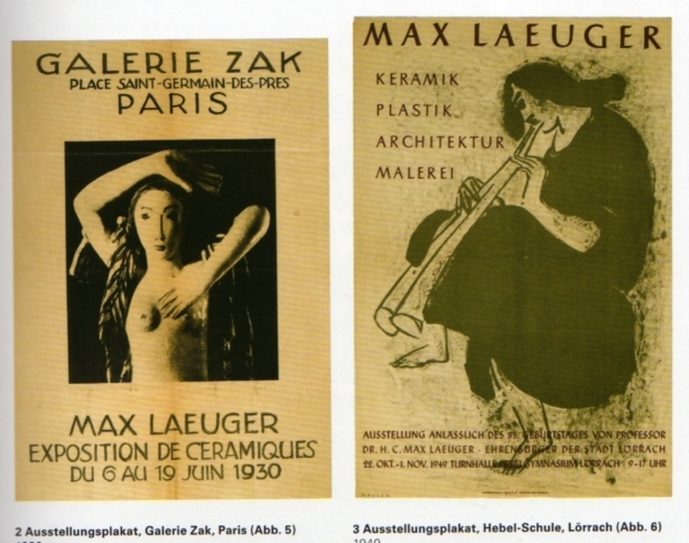

Two late exhibition posters reproduced in MAX LAEUGER.

Two late exhibition posters reproduced in MAX LAEUGER. Because of its potential for serial productions, ceramics over the centuries has often been the most generally accessible expression of the high art forms of the time, even though serial production has usually tempted the larger companies to produce to the most popular taste. That tension between the creative and the popular was certainly evident at Karlsruhe, where the modernist work of Laeuger, Paul Speck, and Marthe Katzer stood out sharply from the ever marketable baroque. Before there were cheap prints, colour TV and museum tourism, it was jugs, vases, teapots, cigarette boxes and tea caddies that led much of the ‘democratization’ and dissemination of both aesthetic shifts and their underlying ideologies.

The editor of Max Laeuger: Gesamt Kunst Werk, has assembled an impressive cross-section of Laeuger’s work throughout his career – his watercolours and other graphics, his ceramics and ceramic sculptures, his architecture, his furniture designs, his stained glass work, his public monuments, and his garden designs. Rather than following his development chronologically, he has provided fourteen chapters on the different areas of his art, focusing mostly on the mature work of the 1920s. Compared to the still indispensible 1985 monochrome catalog and index to Laeuger’s work by Elizabeth Kessler-Slotta (Max Laeuger 1864-1962, now so rare it sells for between $500 and $1000 a copy) this is a sumptuous book, with 407 illustrations, more than half of them in colour. Unlike the Kessler-Slotta, which presents little work later than 1930, it includes watercolours as late as 1950 and fragments of ceramics recovered from the ruins of his studio after its 1944 destruction. It is likely to go out of print quickly. The book’s only significant structural deficit is its lack of an index.

FD

RSS Feed

RSS Feed