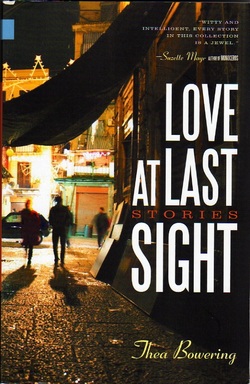

The blurbs for this book – from older writers in the two westernmost Canadian provinces – stress how well-written and “intelligent” the stories are. I wonder whether very many read a book because it is well written or wise. I think most want more – which Love at Last Sight definitely offers. The cover copy also dwells on how allusively literary the stories are, as if that might sell copies. But it’s not the stories that are allusively literary; it’s the young-woman narrators of the stories, usually would-be writers or artists, who are characterized by Thea Bowering as obsessively literary – as drifting in a global world they perceive as having been oppressively and decisively written, written again, and overwritten.

THAT I find interesting: i.e. how can one function as a writer when it seems that all possible writing has already been done? How can one even navigate in a world that seems so overwritten that there is nothing unwritten, nothing outside of literary discourse, to experience? How can one be an edgy writer when the edges seem to have been long ago honed and all the incisive lines inscribed by the famous and recently famous names – Homer, Sappho, Shakespeare, Shelley, Keats, Baudelaire, Tolstoy, Flaubert, James, Bakhtin, Yeats, Williams, Woolf, HD, Benjamin, Synge, Orwell, Duncan, Cage, Barthes, Calvino, Derrida, Kroetsch, Berger, Sontag, Blaser – including also one George Bowering, to whom this book is dedicated? So many texts are quoted or incorporated in Love at Last Sight, from all of the above plus numerous texts written, sung or spoken by popular performers, that the collection concludes with nine pages of detailed credits. Nine pages of cheerily disguised anxiety of influence.

The title certainly conveys some cynicism – that one loves most at the moment of loss or departure. Most of the characters in these stories are reluctant to invest emotionally in their relationships, as if the already-written and multiply digitized world in which they live has no more promises not only of creativity but also of happy endings or

I learned how to order ice cream in Italian, eat it from chilled metal cups. It was delicious, then gone. Then it was on to another beautiful thing.

I learned to take the mundane with the exceptional, the ugly with the beautiful – none of it belonged to me. I had discovered nothing on my own. I couldn’t remember the names of places we travelled to, or how we got there, only the images. As I got older, I watched other people find their passions, or at least settle on the things that made sense to them. I, however, went on to whatever thing was next, for a while thinking it would bring me, finally, to some place. (“To the Dogs,” 238)

... at university, she came across something about this feeling she’d had, in an essay by John Berger. Though the images are haunting and grotesque, he says, Hell is mostly a matter of space ... There is no horizon there. There is no continuity between actions, there are no pauses, no paths, no pattern, no past and no future. There is only the clangour of the disparate, fragmentary present ... nowhere is there any outcome. Nothing flow through: everything interrupts. There is a kind of spatial delirium.

This delirium was what Eira felt, sitting in front of Matthew’s photos. (“The Sitter,” 178)

Much like Canadian novelists Gail Scott and Daphne Marlatt, Thea Bowering plays a peek-a-boo- game with autobiography, not only having many of her narrators recall similar parents or work in an Edmonton bar, but even giving Clara, the narrator of the opening story, the surname “Bowering.” This game is probably why she writes in her acknowledgements – possibly with a fictitious tongue-in-cheek – “I am not a realist writer, all characters in this book are fictitious; any resemblance to real people is purely coincidental” (274). This is the subtly oxymoronic and less subtly fictitious statement that writers who play the autobiography game are often moved to make. Personally, I don’t believe in a realism-fiction dichotomy – we are all fictions to ourselves, made up from scraps of discourse, even – or perhaps most intensely – when trying to convey the ‘real’ story. That’s one of the useful implications of this sometimes painful collection. “The fiction makes us real,” Kroetsch famously quipped. And some of us, like this Bowering and her characters, make up our fictions more interestingly than others.

FD

RSS Feed

RSS Feed