Like Al Purdy, I also go far back in time with Earle Birney. In 1955 he signed his newly published novel Down the Long Table for my godmother to give me for Christmas; in 1957 I began seeing him, tall and slightly stooped, on the UBC campus; in my third year in 1959 I enrolled in his Chaucer class and sat in the back row where I wondered whether he ever saw me. Always theatrically self-creating, he played each day to an appreciative audience of graduate students who had preempted the front row. He savoured speculatively the Wife of Bath's portrayal, “Housbondes at chirche dore she hadde fyve, / Withouten oother compaignye in youthe,” and spent much of another class pondering new research into a rape charge that Chaucer had faced, and whether “raptus” could mean that he had only kidnapped the young woman, and perhaps not for himself, possibly for John of Gaunt. Stimulating stuff for a country boy like me or Al Purdy – wouldn’t have missed a word of it. In a 1969 letter to Purdy, however, Birney remembers: “I think he got firstclass marks from me; but he scarcely ever attended my lectures” (213).

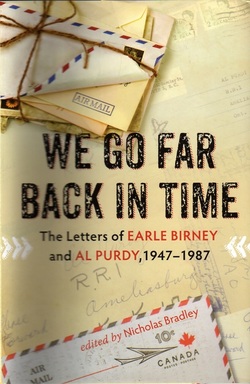

Purdy writes three letters to Birney in 1947, while trying to get poems accepted by him for the Canadian Poetry Magazine, which Birney was editing, and begins a more personal correspondence in 1955, with letters that editor Nicholas Bradley here terms both “pugnacious” and “sycophantic” (15). Much to his credit, Birney replies, with patience and good humour. The two poets’ correspondence continues until Birney’s devastating heart attack of 1987.

Bradley describes his aims in this collection as “primarily curatorial” (30). He has seemingly reproduced all currently available letters exchanged by the two, deleting only brief passages “that seem to me gratuitously offensive, tactless, or cruel about people who are not public figures” and a “few” that disclose “sensitive medical information about” Purdy’s wife, Eurithe (32). He notes that there are frequent gaps in the correspondence where letters appear to be missing – possibly lost, or not yet catalogued, or contained within the numerous cartons of Birney papers still under embargo. Birney was notoriously protective of his public reputation, and within his lifetime prevented researchers from accessing any materials associated with his first wife, the teenage Trotskyist Sylvia Johnstone, or lovers such as

A large part of the potential interest that the collection holds comes from its being a book of representations – representations of the writers to each other, representations by them of others. Birney casts himself as wise, urbane, a successful sexual adventurer, a macho drinker and a modestly successful poet somewhat desperately struggling for additional recognition and international success. Purdy presents himself for much of the book as impressed by Birney’s poetic and sexual successes, and by the passion of his desperation, and as also sexually liberated, similarly misogynist and heavy-drinking, and earnestly struggling to educate himself toward similar recognition as a poet. Purdy’s self-representations are less extreme but also often less supported by the events he describes. Is he really the Lothario he wants Birney to believe he might be? He offers no names, no anecdotes.

Purdy sends numerous poems to Birney, seeking both advice and reassuring praise. Birney sends only one to Purdy – and to impress rather than elicit critique. He often portrays rival writers contemptuously. Here he describes a 1969 Vancouver reading-performance by the New York (not “San-Fran”) conceptual poet Jackson Mac Low – a performance for which I drove from Victoria to participate in.

He [Gerry Gilbert] & the old blackmountaineers (Tallmans, Hindmarch, Daphne Buckle)

acted as solemn acolytes to a priesting job by Jackson Mac Low, latest San-Fran luminary

to be given the purple crapet [sic] treatment (I like crapet). Mac Low drops the concretist

mask when he comes up here and is just one of the Olsonites, humourlessly gasping out

short-line deadpannery with however bits of Michael McClure’s grunts thrown in & the

extra pitch of “random mass reading’ which doesn’t mean, as most of the UBC student

audience thought, any involvement in the audience (how can blackmountaineers involve

with such stupid people as audiences? Faugh!) But means Gerry-Daphne etc humbly and

very rehearsedly reading bits and scraps of the great Mac Low’s ‘found poetry’ ... (185)

Purdy usually represents rivals more charitably and, when he doesn’t, decides that he must have a “mean streak,” a mean streak that is perhaps forgivable because of the struggles he is undergoing. They both tend to regard younger poets not as potentially innovative but as incomplete. If the younger poet has not offended them either directly, or indirectly through their affiliations, they portray him (most often a him) as promising – Andy Suknaski, Barry McKinnon, Phyllis Webb – if he has so offended, they portray him as limited, failed, unpromising – bill bissett, Gary Geddes, John Robert Colombo. In one letter Birney offers Purdy this overview:

MacEwen (obscure), Nichol (essentially a mixed media man, not exhibitable in a

straight anthology), Kiyooka, Webb (strange fruit), Ondaatje and Finnigan and Jones

and Procope (amateurs), McCarthy (one good poem), Page, Anderson, Roberts, Pratt,

Marriott, LePan, Spears, Mandel, Macpherson (writers in traditions already dead),

Gustafson (always just misses the boat because he is so anxious to make it). (196)

But Birney would be unlikely to make these unfavorable appraisals publicly.

Another fascinating aspect of the book is the vivid way in which it portrays a crucial period of change, 1955-75, in Canadian Literature. A major part of this change was the establishment of the Canada Council, various provincial arts councils, and with them institutions such as the League of Canadian poets, the literary reading series, the travel grant, the writer-in-residence. Both poets portray themselves as desperately poor, and eager to milk the “CanCow,” as Birney calls the new Council, and other grant sources for every possible penny – even in the late 1970s when Birney is a pensioner and Purdy appears to have fairly regular income from articles and poems in commercial magazines. They repeatedly exchange images of themselves as driven by grants and publishing obligations, frantically trying to complete book, reading tour, and travel grant commitments simultaneously, while also creating new and saleable poems in each exotic site traveled to. Birney’s claims of poverty often seem to stem from his need to maintain more than one residence because of having relationships with more than one woman.

Both men’s literary creations are thus mostly ad hoc. Neither has a sense of what they aim to accomplish through their poems, beyond keeping themselves capable of writing one more and thus producing the quantity which will keep grants, reading series invitations and writer-in-residenceships coming. Neither professes any sense of a cultural dimension in their poetics – poetics which are largely pragmatic, based on a desire to simultaneously fit with and stand out from current poetic practice. Their main daily goal appears to be to write one more “good poem.”

The second aspect of this period in Canadian culture is the emergence of a professional literary criticism – one supported by regularly appearing journals and a variety of active scholarly publishers, based on peer-review, blind-vetting, annual academic conferences, and scholarly research grants, and focused on texts more than on their writers. Both Birney and Purdy have assumed that criticism is about writers, and that if you can’t speak well of a living writer you shouldn’t speak ill. Birney tells Purdy (in a statement reprinted on this collection’s back cover), “The truth is none of us who write poetry should allow ourselves to make public critiques of the others, not in a small country like this where we know each other too well.” In an appendix that Bradley includes, Purdy writes to Robin Mathews in 1974, “I don’t have a very high opinion of the Davey book [on Earle Birney] on accounta [sic] when you start to do a book of this nature on a Canadian writer it isn’t worth doing if you intend to make it partly a put down” (444). (This “Davey book” – somewhat amusingly – is one on Birney which, in June 1969, I had been persuaded to take over the writing of by Gary Geddes, the publisher’s editor, and by Al Purdy, who was backing out of the original contract to write it, and who then let two months pass before finding the courage to inform his friend Birney of the change. Birney was then outraged both by the change and the delay [213] – as well as later by the book.)

Toward the end of their correspondence Birney and Purdy’s letters become somewhat less performative. In 1974, while recovering from his first heart attack, a more sober Birney writes to Purdy:

So stop drinking for jesus sake. Hang on to your brain cells. They are a limited stock,

did you know? (Not just yours, everybody’s.) Every drink permanently destroys hundreds

of cells. Your poetry is what keeps you alive when alive, and after you’re dead maybe too

(if the world lives). Don’t fuck it all up with alcohol.” (294)

Purdy tells his friend in the next year that thinking that it’s one’s “duty” to write poems “makes you feel like a sausage machine” (311) and in 1977 and again in 1978 that being on reading series “makes one feel like an industry” (346; 359). He tells him in 1984 that he is “writing a critique of CanPo, and wondering if it’s possible to tell the truth” (425), and in 1985 comments “And yeah, I think you are right about travel: it kinda puts the onus on me to produce, like a deadline, a climate and a geography of writing (428)

A surprise to me in the collection was the revealing of Birney’s homophobia, which was not evident to me in his writing, except perhaps when the main character of Down the Long Table worries that he being viewed as a “pansy” (47). The surprise comes in the middle of an otherwise positive description of a 1970 reading at UBC by the Yorkshire poet Basil Bunting from his long poem Briggflatts, during which several of the Vancouver and 'Black Mountain' writers Birney habitually disliked sat with Bunting on the stage.

... who the hell the Elizabethan Nobles were ranged around the back of the stage. I

recognized robin blaser, warren tallman, robert duncan, robert creeley, stanley persky

– I thought it was meant to be an orchard arrangement or FRUIT BOWL. But there was

also huge Lionel Kearns with his tiny Maya & a lot of others who looked practically

heterosexual.

In fact only Blaser, Duncan, and Persky, among the names Birney left in nastily-intended lower case, were gay – not that this distinction matters, except to point to the extent of Birney’s intended insult. He then continues, telling Purdy that he had missed the after-party because “I wasn’t invited to it until 5 minutes before it was to start (though I’d heard of it a week earlier) so I got more lift out of telling the usual faggot-messenger from the UBC English Dept. to go screw himself” (229). In replying, Purdy is rather more circumspect. He explicitly repeats only the lower-case part of the insult, writing “Do think the blaser, creeley, duncan, tallman lineup behind him [Bunting] sounds revolting, not to say throwupable. [...] these goddamn in-groups don’t know a good poet unless he’s an actor like Bunting” (231).

Interestingly, Elspeth Cameron reported in her 1994 biography that Birney’s undergraduate mentor at UBC, the legendary “larger-than life” department head Garnett Sedgewick, who lectured with “dramatic flair” (Earle Birney: A Life 45), excluded women from his classes, and attracted a dazzled young Birney from the study of chemistry to that of literature, “was homosexual,” as were several of his other male honours English students.

Sedgwick was homosexual, and David Warden [the model for the David of Birney’s 1940

long poem “David”] was – like Birney – one of his favorites without being lovers. But it

had been at UBC in 1925-26 that Birney had briefly (and unsatisfactorily) sampled

homosexuality with the flamboyant young professor Frank Wilcox who remained his

friend. Leonard Leacock, one of Birney’s Banff [mountain] climbing friends, was also

homosexual. (509-10)

Cameron theorized here that it was fear of “closer examination of these relationships” that caused him to react so vehemently whenever critics, such as Dorothy Livesay, had considered links between “David” and Birney’s own mountain-climbing experiences (510). That the memory of them may have helped trigger Birney’s homophobic outburst here against the similarly flamboyant Robert Duncan and Robin Blaser, and against the English department in which he’d first been attracted to literature, is I suppose also possible.

In his notes to Birney’s letter about the Bunting reading, Bradley comments only that Stan Persky “belonged to the circle of Robert Duncan, Jack Spicer, and Robin Blaser in San Francisco in the early 1960s and emigrated to Canada in 1966,” leaving it to the reader to know that all of Duncan, Spicer and Blaser were publicly gay. Bradley has twice noted earlier the distaste which Purdy had felt toward the Tish-group writers George Bowering, Fred Wah, Daphne Marlatt, Gladys Hindmarch and myself (52, 185), but does not comment here or elsewhere on the extreme enmity which Birney also bore toward them, their supporter Warren Tallman, and the older US 'Black Mountain' poets Robert Duncan, Robert Creeley and Charles Olson whose writing they admired. Only Bowering was ever able to negotiate his way to both Birney’s and Purdy’s approval – far back in time.

FD

RSS Feed

RSS Feed