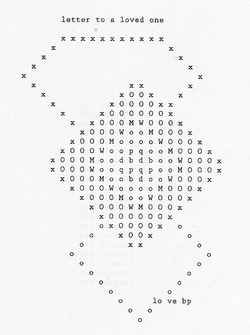

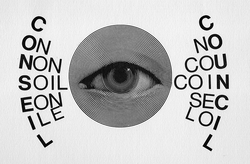

bpNichol, “Letter to a Loved One,” 1967.

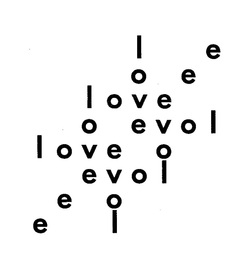

bpNichol, “Letter to a Loved One,” 1967.  bpNichol, “Blues,” 1967.

bpNichol, “Blues,” 1967.

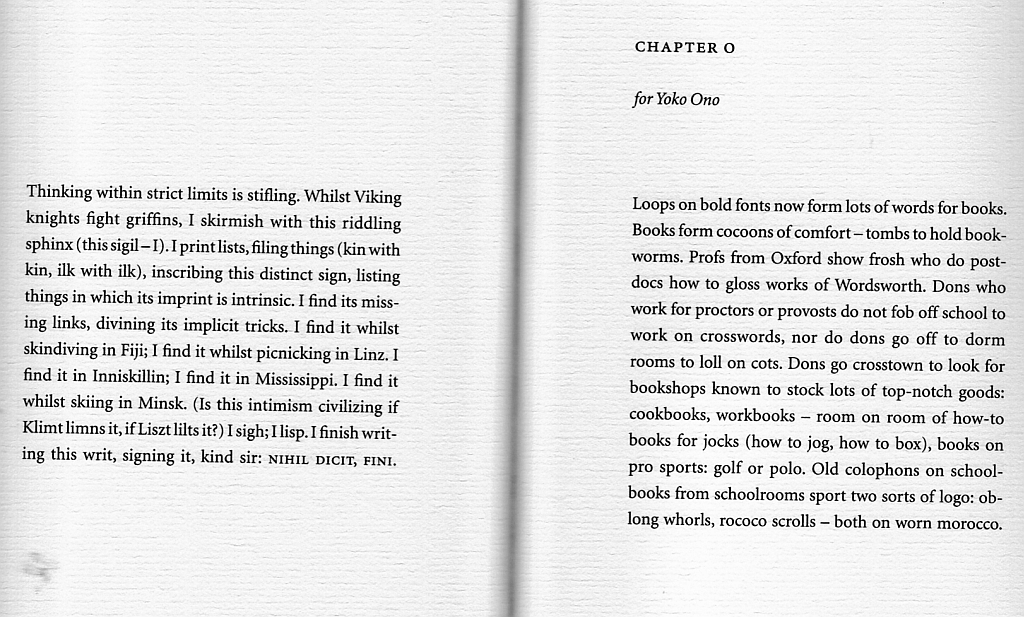

(sections 4-20 via "Read More" below)

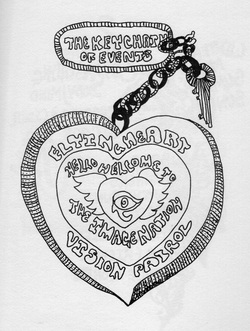

Judith Copithorne, "The Keychain of Events, 1973.

Judith Copithorne, "The Keychain of Events, 1973.  Earle Birney, "Canada Council," 1969.

Earle Birney, "Canada Council," 1969.  bpNichol, STILL WATER, 1970.

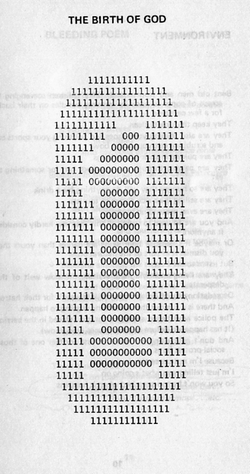

bpNichol, STILL WATER, 1970.  Lionel Kearns, "The Birth of God," 1965.

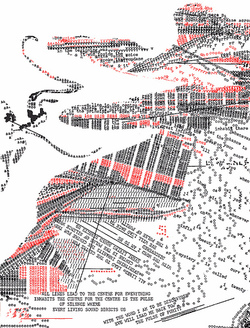

Lionel Kearns, "The Birth of God," 1965.  Steve McCaffery, from CARNIVAL, 1973

Steve McCaffery, from CARNIVAL, 1973  Peter Jaeger, from RAPID EYE MOVEMENT, 2009.

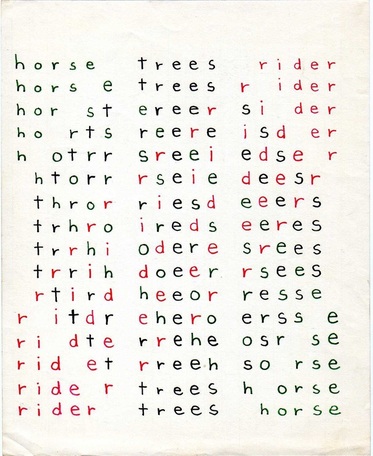

Peter Jaeger, from RAPID EYE MOVEMENT, 2009.  bpNichol, "Horse Trees Rider," 1972.

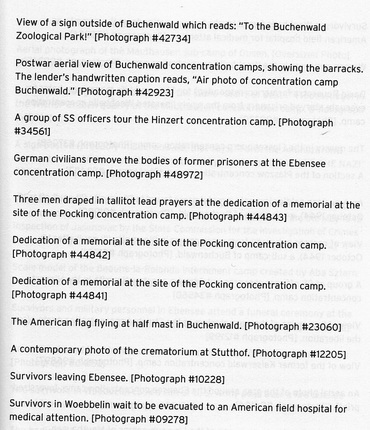

bpNichol, "Horse Trees Rider," 1972.  Robert Fitterman, page from HOLOCAUST MUSEUM, 2014.

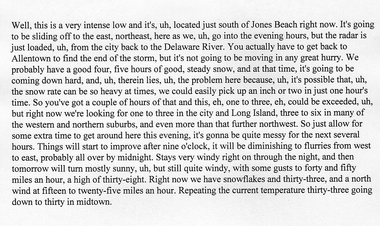

Robert Fitterman, page from HOLOCAUST MUSEUM, 2014.  Kenneth Goldsmith, from THE WEATHER, 2005.

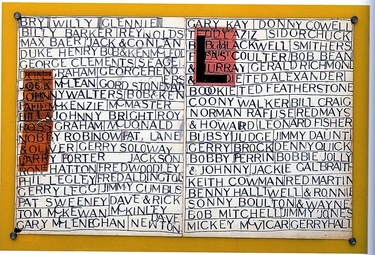

Kenneth Goldsmith, from THE WEATHER, 2005.  Greg Curnoe, “List of Boys I Went to School With,” 1962.

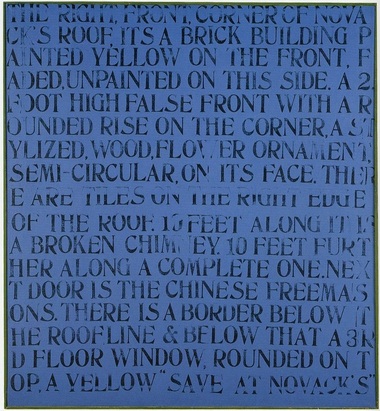

Greg Curnoe, “List of Boys I Went to School With,” 1962.  Greg Curnoe, "Left Front Windows," 1967.

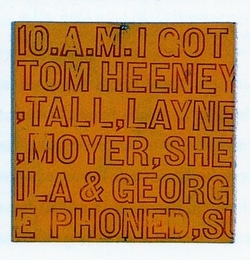

Greg Curnoe, "Left Front Windows," 1967.  Greg Curnoe, from "24 Hourly Notes," 1966.

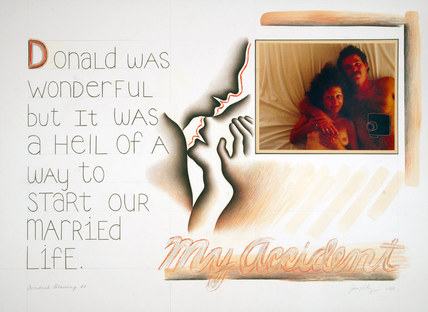

Greg Curnoe, from "24 Hourly Notes," 1966.  Judy Chicago, "Accidental Drawing 20," 1986.

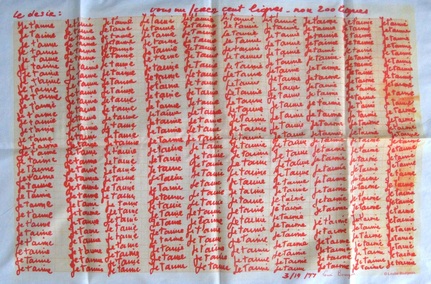

Judy Chicago, "Accidental Drawing 20," 1986.  Louise Bourgeois, "Je t'aime," 1977.

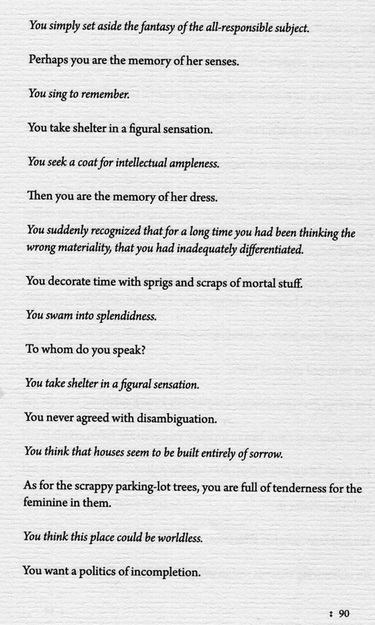

Louise Bourgeois, "Je t'aime," 1977.  Lisa Robertson, page from CINEMA OF THE PRESENT, 2014.

Lisa Robertson, page from CINEMA OF THE PRESENT, 2014.  Robert Fitterman, page from NO, WAIT. YEP. DEFINITELY STILL HATE MYSELF, 2014.

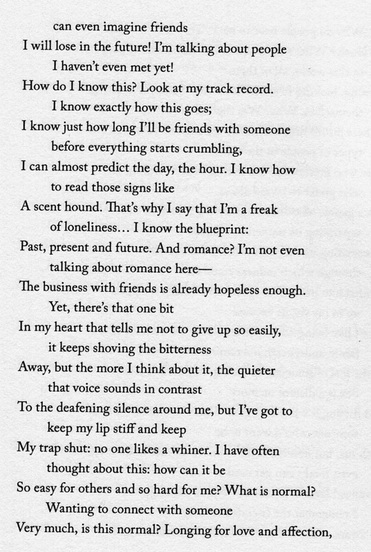

Robert Fitterman, page from NO, WAIT. YEP. DEFINITELY STILL HATE MYSELF, 2014.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed