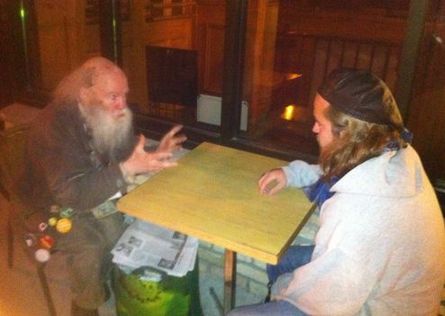

Roy MacDonald & interviewer Kevin Heslop

Roy MacDonald & interviewer Kevin Heslop Roy McDonald, possibly London's most well-known citizen, will be the featured poet at the October 1st, 2014 London Open Mic Poetry Night at Mykonos Restaurant.

Roy was born in London in 1937 to the tuning of global war drums. He has since been an active member of the demonstrative community: he participated in the call for universal civil rights, environmental awareness and an end to the southeast Asian bloodbath of the 1960’s and 70‘s, and, more recently, denounced and supported the American invasion of Iraq in 2003 and the Occupy movement of 2011, respectively.

1970 met Roy with the publication of his poem “The Answer Questioned”, a stream of idiosyncratic puns which found the January edition of 20 Cents Magazine; it was reprinted and bound in 1979 by ERGO Productions and twice since by Conestoga Press. In 1978, ERGO productions again favoured Roy with the publication of “Living: A London Journal”. In 1979, Don Bell’s “Pocketman”, a novel which loosely follows Roy’s “wanderings and exploits”, was published by Dorset Publishing. A play about Roy’s life entitled “Beard”, written by Jason Rip, found the ARTS Project theatre in 2012 under the direction of Adam Corrigan Holowitz. After decades of transience, including residence in Montréal and Rochdale College in Toronto, all the while comforting the disturbed and disturbing the comfortable, Roy presently lives in his childhood home in London, Ontario.

The Interview

(Interview by Kevin Heslop for London Open Mic Poetry Night)

Despite the fact that this interview – originally an eight-thousand word transcript – has been segmented into themes, it retains the linearity of the conversation between Roy, Stan, and I. Roy’s words have been reproduced in their original form with some minor, faithful sculpturing in the interest of clarity. Put another way, the following consists of the two fillets of a single tuna, cubed raw. K.H.

On Writing

KH: Do you feel any obligation, speaking specifically of poetry, to your reader? Or do you write solely for yourself?

RM: I think a writer writes for both. There are different ways of writing, different reasons people write poetry or anything else. If we talk about poetry, it’s a way of thinking, a way of therapy. It can be very good therapy. You know, someone breaks up with one’s girlfriend or one’s girlfriend breaks up with you, and then you write a poem about the heartache. It helps. To write about the relationship can be very helpful. And another reason, of course, is memory. When I recite a poem... There’s a whole different feeling when one recites a poem than when one just reads a poem.

And [at] most poetry readings, people read their poems. I’ve made it a point to memorize a lot of my poems, and that just makes it easier to get directly to the other person because you’re not just reading it from a sheet of paper or a book. And if I’ve had certain memorable experiences, I write about them, and then when I read them to myself, to others, to an audience, to one person, to a group, the feelings come back that I wrote the experience about. And that’s valuable too.

KH: What do you think about structure in poetry? Meter. Form. Is it important? Is human communication through poetry best when structured, metered, and rhymed?

RM: Well, you know, that’s how it used to be in the oral cultures. With all that structure, poems are easily remembered because they’re rhyme schemes and so on throughout the centuries. And now we don’t need that. Denise Levertov. Have you ever heard of her?

KH: No.

RM: British-Russian background. Wonderful poet. She was an activist poet as well, as Margaret Atwood is. I really admire that in a poet. As is Robert Bly. Opposing the war in Viet Nam... [But] Denise Levertov talks about organic structure. It’s as you write it; it’s as your thought, your breath, your own individual way of doing it. And that’s what I do. I don’t start worrying about rhyme scheme and so on, anything like that. And people say what I’ve written ‘is just prose. That isn’t poetry.’ And I don’t c-, you know. Call it prose, you know. I call it poetry. A key thing about having something written as poetry is the lines, rather than the paragraphs. You know, like the right hand margin?

KH: OK.

RM: OK. And prose is written right to the end of each sentence, right? With poetry you have the white space around it?

KH: Mhm.

RM: Well, the white space in the lines, the way poetry is structured in stanzas, indicates pauses and helps you pause. And, rather than rushing through a statement – I’ll read political things, I’ll just rush right through... Poetry, partly because of the structure, slows you down and makes you... contemplative.

-

On Friendship

Did I tell you about the anecdote about how when I met Leonard Cohen, reciting one of his poems to him?

KH: Go ahead.

RM: Well, I met Leonard Cohen in Montréal in a bar called the Winston Churchill. And I sat with him, with a group, a small group of people. We were talking. And about half an hour after I’d met him I told him how I recited a poem that he wrote at a friend’s wedding ‘cause she liked the poem so much she wanted me to recite it at her wedding, and I did. And he said, ‘What poem was that?’ And I said, ‘It’s called “Song.”’ And he said, ‘”Song?” What’s that?’ He’d forgotten, or he didn’t; you know, you write a lot of poetry. ‘Song,’ he didn’t remember, and he didn’t know what I was referring to and so I said, ‘Well, I can recite it for you if you like.’ And I did and this is it:

Song

I almost went to bed

without remembering

the four white violets

I put in the button-hole

of your green sweater

and how I kissed you then

and you kissed me

shy as though I’d

never been your lover.

And at that point – beautiful poem – at that point we’re sitting around a table like this, and he gives me a hug. Now, I’d met him half an hour earlier and he gives me a hug. And I said, ‘Wow,’ you know. ‘What’s that for? Because you couldn’t remember the poem?’ And he said ‘No, the way you recited the poem brought back to my mind the experience I wrote the poem about and for that I am appreciative.’

Now that meant a lot to me. When a person is a poet you admire and if a person remembers your poetry so well they can recite it, even one poem – I’ve found that myself – that means a lot.

And I’ve done that with other poets as well. I’ve made it a point to. I know maybe about at least a hundred poems by heart. Several of mine, but those of Keats, Shelley, Wordsworth, Blake, Canadian writers, American writers, British writers, modern writers, and they come in handy to me when I’m going through certain experiences. And, because they’re in my head, I don’t have to have any paper, any books. I can just recite them like I could the poem that I recited that Leonard Cohen wrote.

-

On Self, Personal Influences and the Arts

KH: You mentioned [when we last spoke] that you’re a Jungian, or if you prefer, that Jung is the psychoanalyst with whom you most identify. I’m curious as to who else has shaped your philosophical foundation, say, or your sense of self? People you’ve known, or who have lived, with whom you most identify?

RM: Well, I did mention before Roberto Assagioli, the founder of psychosynthesis. It’s a whole psychological system and I am a qualified psychotherapist as a psychosynthesist-psychotherapist. Roberto Assagioli was a Venetian born in Venice. The worldwide center of psychosynthesis is in Florence. It’s a beautiful system that includes the Spiritual in the broadest sense, as does Jungian psychotherapy. And I’m into the Spiritual in the broadest sense. Again, the Spiritual...

KH: As different from the religious.

RM: Yeah. That’s an important distinction. I think that we are all spiritual beings. We’re not earthly beings having a spiritual experience; we are spiritual beings having an earthly experience.

KH: What do you think about the idea of soul?

RM: *slightly exasperated sigh*

KH: Or... are you a materialist, in other words?

RM: No. I’m an anti-reductionist and a non-materialist. In other words, you know the concept that our thoughts, our minds, are just epiphenomenon of the brain? I don’t believe that at all.

KH: What do you think our thoughts are, then?

RM: Well, the concept that I hold to is that we are part of a soul, a universal soul. Everything is tied together. And even quantum mechanics, quantum physics, tells you that. We’re all interdependent. We couldn’t last for five minutes if it wasn’t for the air around us. And the air around us is exchanging molecules from you and I and from other people and so on. We are beings in the environment. We can’t last without the grass, without the trees, without the animals.

KH: But that doesn’t necessarily mean that thoughts aren’t material.

RM: Again, what is material? When you get back to energy, it’s all energy. We live in an energetic universe. That this *indicating a chair* can be turned into energy or back into matter. We are not just our brains and our bodies. I’ll put it that way. We are much beyond that.

I like the concept that we are ‘not just our skin-encapsulated egos.’ Alan Watts used that term. I like it. It’s a very good term. I’m not just what’s inside here. I’m part of all of this. As Tennyson said in Ulysses, ‘I am a part of all that I have met.’ And Walt Whitman makes the same kind of comment, as did Richard Maurice Bucke, another person that I admire. I mean, people I admire, you know I could go on for an hour about different people that I admire, including poets. I think poetry should be a part of the furniture of one’s mind.

KH: That’s a fine phrase.

RM: You like that? Yeah. Being able to call on poetry. And art as well. I’m a lover and appreciator of art, good art. From the ancient cave paintings to the modern work of... modern Canadian and American painters. People like Greg Curnoe, Jack Chambers. These are London-area painters. Emily Carr. The Group of Seven. The arts are incredibly important. And yet, we know what’s happening with funding, eh? The arts are the first to go because they’re frills. People consider them as airy-fairy stuff... Well, what do we remember of past civilizations? Do we remember the millionaires and the rich people, or do we remember poets and writers and artists?

KH: But, I guess one of the arguments that could be made against art – just to entertain the thought – that could sort of relegate it to the fringe in terms of funding, would be that it’s not as functional as, say, a bridge or a repaired road.

RM: Yeah, but you see, to me it is not either/or. That’s the mistake that people make. Are you going to put the money into art and culture or into things like hospitals and things that that are needed. We need both. You know the statement, and it’s a good one: Jesus [said] ‘Man does not live by bread alone.’

-

RM: I’m very much into a concept and approach, and this is not original by any means, of Inner-Companions. And since we’re talking about poetry, poets and poetry and poems as Inner-companions. And I think of this when I think of a favourite poem of mine that’s inspired me. And I think of, say, a poem by Walt Whitman. I think of Walt Whitman. I think of him as a person. I think about how he was here in London visiting Richard Maurice Bucke in the London Psychiatric Hospital. I think of poets I know. When I read a poem by Margaret Atwood I can remember first meeting her, talking to her. Same with Leonard Cohen poems. [with] F.R. Scott who died a number of years ago. F.R. Scott, Frank Scott, wrote a wonderful poem called ‘To Anthia’:

When I no more shall feel the sun

Nor taste the salt brine on my lips;

When one to me are stinging whips

And rose leaves falling one by one,

I shall forget your little ears,

your crisp hair and your violet eyes

and all your kisses and your tears

will be as futile as your lies.

Now, when I met Frank Scott, I recited that poem to him. And again, we were talking earlier about how you recite a poem that you’ve memorized to a favourite poet and... it’s such a wonderful feeling. And I’ve had that, when people have memorized poems of mine and can recite them back to me. And I did that with Alden Nowlan as well. You know Alden Nowlan?

KH: No.

RM: New Brunswick poet. Underrated. Written something like 20 books of poetry. One of the best Canadian poets of the last century. He died relatively young, I think in his fifties. He was pretty young, but he was a great, great poet. And I met him, talked to him. And I’ll just recite one more poem.

To Nancy

Nancy, I’ve looked all over hell for you.

Nancy, I’ve been afraid that I’d die before I found you.

But there’s always been some mistake:

A broken streetlight, too much rum,

Or merely my wanting too much for it to be her.

Do read Alden Nowlan, you know, if you get a chance.

-

On Vice

KH: You know, the word rum came up in the poem and maybe it’s too general but what is the apparent draw towards vice? Artists traditionally, historically, have been drawn towards vice, and I was wondering if you had an opinion as to why.

RM: I disagree with your premise. Maybe you need to articulate more what you’re...

KH: Say, Kerouac was an alcoholic. Bukowski was an alcoholic. Ginsberg smoked cigarettes for much of his life. William S. Burroughs was a junky for a lot of his life. Say, Rimbaud, coming out of the opium dream...

RM: Well, a great many of these people, as you know, destroyed themselves. And, sooner or later – Rimbaud stopped writing poetry when he was 19 or 20. You burn out. Live fast, love hard, die young? OK, if you want to go that route. I don’t. And most of the world’s greatest poets didn’t. Including, uh, Walt Whitman wasn’t an addict...

Stan Burfield: You definitely can speak from that point of view, can’t you, because you’ve lived a lot longer than any of those people.

RM: And I’ve been there. I’ve been there.

SB: Oh, that’s right, yeah.

RM: I’ve been there. Don’t forget that. I talked about that [last time we spoke], that I was severely mentally ill for a number of years, for quite a few years, almost dying as a consequence of my mental illness. My mental illness was alcoholism. That is a mental illness. It’s named as such.

KH: Do you think that there’s any truth to the idea that there are certain substances which allow you to tap into a higher consciousness that you would otherwise have allowed to go unnoticed should you remain sober? LSD, for example, has been said to open your mind to -

RM: Yeah. But again, when you’re talking about drugs, there’s a great differentiation between the opiates, alcohol and other kinds of drugs and the psychedelics. So, we need to be very careful about what we’re talking about here. Yeah. Ayahuasca, LSD, psilocybin, peyote. Some of these can definitely open you up.

KH: Have you got an opinion on why there has been, at least in modern, Western civilization, a War on Drugs, as it’s called, why the ban of these substances which seem to be able to expand consciousness?

RM: Well, the powers that be don’t want that, obviously, because what would happen if everyone started thinking for themselves?

KH: Do you think that’s a conscious decision rather than an avoidance of...

RM: I think it’s that, and I think it’s the fact that the alcohol lobbies are tremendously important. Do they want people smoking up? I’ve been to parties at Western and so forth. It used to be, at the Homecoming weekend, people were so drunk and fights and so on. And I’ve been at Woodstock where hardly anybody drank. A lot of people smoked up and it was a very peaceful scene, right? The difference between those drugs, for example. And there’s obviously a danger with these things, with mind expansion. I took morning glory seeds...

KH: LSA...

RM: It’s similar to LSD. I had a whole heaven, hell, rebirth experience. And it was so scary that afterwards I had flashbacks. Never again. I never touched anything like that again, mushrooms, anything. And yet I continued drinking and that was what was killing me. That’s the interesting thing. I was stupid. I didn’t know any better. And I drank alcohol for many reasons. It was an all-purpose drug for me. I felt sad. I drank. I felt a bit better. I felt really anxious, a few drinks, ah, I felt better. I was very shy. I’ve always been a shy person, very much an introvert. We’ve talked about that. If I was sitting here sober and there was a beautiful woman sitting over there and I wanted to meet her, I would never think about going over and introducing myself because, ‘Oh, she’s probably busy or waiting for her boyfriend or whatever.’ A couple of beers in me and I’d go over and introduce myself. A couple of more beers, I’d introduce myself and start hugging her. A couple of more beers, I’d be feeling her up. And a couple of more beers, if she was with a guy, I’d tell the guy to f-off and then start caressing her. It’s a wonder that I’m still alive, you know? I mean, really, it is.

-

KH: If you were to choose one thing that you’re most proud of, that you’ve done or that you’ve participated in, could you narrow it down?

RM: Yeah.

KH: What would it be?

RM: Attaining sobriety! Stopping drinking.

SB: Why are you so proud of that?

RM: Because I was finally able to do it, and if I hadn’t done it, I would have destroyed myself. I’d be dead now. I wouldn’t be here. And it was difficult. As I said, alcohol is an all-purpose drug. If I felt sad, I would drink. If I felt happy, if I felt good, a few drinks and I’d be flying. And then the depression sets it. But really, it’s an all-purpose drug.

I was under the illusion that I couldn’t get through my days and nights without alcohol. It was that much of a crutch. And it was a rubber crutch. As I found out later, I could. I could get through without it. But I went through some very difficult times after I stopped drinking, but I’ve never had a relapse, fortunately. Very fortunately, because a lot of people do relapse and fall of the wagon.

SB: Yeah, some strong streak in you. Some determined...

RM: Yeah, but also feeling, ‘If I don’t, I’m gonna die.’ When you really face death, looking at you in the face, there’s death: do I want to live or do I wanna die. When you face that, it’s very scary. But it’s pretty sobering, too. And also, memory is very important to me. Jack Kerouac was called ‘memory babe’. That was his nickname because he had an incredible memory. And I have a very good memory as well. But, again, when Kerouac would drink more and more, you know, it screws up your memory! And I didn’t like the fact that I’d be out drinking, and I’d go out to the bar that I drank at the night before, and they’d say ‘Get out of here McDonald, you’re barred.’ ‘Why?’ ‘After what you did last night?’ ‘What’d I do last night?’ ‘Oh, come on. You know what you did.’ ‘Oh, no, I did? Oh, no...’ And so it went. And I did want to remember but I’d brown out, you know, when you remember just bits and pieces? And then black out. What? What happened? And you know, waking up in jail and wondering, how did I get here? What’s the charge? I mean, when you’re thrown in at night. What’s it gonna be? Drunk, or assault, did I hit a cop? I didn’t know. Scary, very, very scary. And again cops could have said I was pugnacious and I hit him. Assault. That’s assaulting a police officer. And it was never that, it was always drunk in a public place. And then it was a 30 dollar fine or 30 days in jail. Drunk and disorderly, it was called...

But Ginsberg certainly wasn’t an alcoholic. He did drugs, but they all did. He died at 71 or 72 [70]. Or Ferlinghetti. Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s still going and he’s about 94 or 95, now. Met him as well. And these are treasured meetings with people. Talking to them about their craft is very important to me. And you know Ted Hughes? Britain’s poetry laureate. He was married to Sylvia Plath. And I’ve met two Nobel Prize winners in poetry: Joseph Brodsky, a Russian poet, and Derek Walcott, a West Indian poet.

-

On Public Image

KH: In your opinion, how is fame positive? How is it negative?

RM: Well, you gotta know how to use fame. It can benefit you, it can hurt you. I get people out there who – and this is not uncommon – who’ll say, ‘Look at this guy, look at his appearance. He’s just a bum, but poetry? Ah, fuck. He’s a loser. He’s an old man.’

I get a lot of abuse and a lot of it is just pure jealousy. I’m out on the street. I’m singing and hugging all kinds of beautiful women. Because I love women, you know. I mean who doesn’t? I guess there’s some that don’t, but I do. ‘So he’s got a couple of books published, so what? Big deal.’ Well, I don’t glory about the fact that I’ve got a couple of books published. I’m glad I have. I’m glad I’ve had a book written about me and a play written about me and so on. And I’m very high profile.

Well, it can be used for you, it can be used against you. I’ve had hassles, like the time I was thrown off the University of Western Ontario campus. I went immediately down to the [London Free Press], I knew people there. They wrote a story about it; I got right back on campus. I knew people at City Hall. I mean, it’s sad in this case, in this society, that if you know certain people. you can have power. You know certain people. Media people, mayors, provincial leaders. ‘Hey, I’ve got connections. Don’t screw me around or I’ll...’ And the poor guy or girl that’s on the street and doesn’t have any of these connections, they’re just nobody. They’re powerless...

When I was thrown off the [Western University] campus, the Chairman of the grounds at the time who issues the orders on the grounds because it’s a semi-private place, the guy who wrote – I can’t think of his name at the moment – an editorial in the Western Gazette on my being thrown off the campus, he asked the guy in charge of the grounds, ‘Does this sort of thing happen from time to time? You know, people come up there from the community who are not students, not teachers and get asked to leave...’ He said ‘Oh, yeah it happens all the time.’ ‘And what happens to them?’ ‘They go away. We never see them again.’ They’ve got no recourse. They’re just riff-raff of London going up to the country club of Western. You can detect a bit of anger, right?

KH: It is a private establishment though, technically, no?

RM: No. Technically it’s like a mall. You can be asked to leave a mall; you can’t be asked to leave the street or in a public place...

KH: Right, but a mall is private property, too, isn’t it? It’s accessible to the public, but it...

RM: No, this goes under the law with regards to schools. Now I can see, say, you or any of us hang around a high school. Obviously, what’s going on here?

KH: Right. Lecherous.

RM: Yeah. Now, with Western or Fanshawe you can be asked to leave with no reason given if you’re not a teacher or a student or a member of the support staff, like a cook, or if you’re working in the bookstore or whatever. You can be asked to leave. And what happens is that it’s open in the sense that there are venues there open to the public. The bookstore is open to the public. Not just the students; it’s open to the public. Events at the stadium are open to the public. Alumni Hall [holds concerts] that are open to the public. They want the public to come. On their terms.

And they lied when they threw me off the campus. They lied to the press when they said that I didn’t have any identification. They thought I was a vagrant. Total bullshit. Bureaucratic bullshit. They knew exactly who I was and why they wanted me off the campus. By the way, I had a whole wallet of identification. They blamed it on the university cops not knowing who I was. I showed them my books. When I get that kind of bullshit and people read the paper and say, ‘They didn’t know who you were.’ Bullshit. They knew exactly who I was. You see what I mean? I’ve dealt with bureaucracies in the past and I know what they can do, how they can screw people around in every way, on every level. Not that all bureaucrats are bastards, but a certain amount of them are. And far too many of them are uncaring, you know. ‘Who are you?’

Like you. Hey! Why are you wearing your hair like that? You’ve got a beard. I don’t like that hat. That hat looks kind of strange. What are you doing up here? You see? You could get that tomorrow. You could go up there and get that tomorrow.

KH: I know I’m privileged in that way.

RM: Why? Because you’re...

KH: Acceptable by society’s standards, more or less.

RM: Oh, more or less. You see, well, it’s just, how far out can you be? How far out am I? Would they ask him to leave? See, it’s not just they know who they’re asking to leave and why. They knew exactly who I was. They knew I was in the cafeteria. I’d get people to think. I’m very well known. They’ve written several stories about me in the [Western Gazette] over the years. They knew me. That and, plus, my appearance. ‘He doesn’t look like a student,’ you know.

-

On Politics

KH: Are there any barriers to communication in particular that stand out to you, or is it too complicated to...

RM: Well, it’s just a complex question. There’s all kinds of barriers to communication, language being one obvious one. And social class, being one. And we’re a classless society. Sure we are. Sure we are. We’re not as [stratified] as the British system.

KH: Does it come down to money?

RM: Money. Power. And they generally go together. Though, a person can have power and not much money; but if they’re in a powerful position, they have the power and they can change things. By the way, I’m 77. I’ve gone through so many things. I’ve seen so many things. And I had to deal with putting my father in Parkwood Hospital. And I had to deal with bureaucracy there. I had to put my aunt in hospital. She had dementia. My father had a stroke from which he never recovered. That’s why he had to be put in Parkwood. My aunt had dementia. She had to be put in a nursing home. And all the bureaucracy dealings that I went through: what I could do, what I couldn’t do, and what they said. Each case was different. With my aunt, they didn’t have an opening for her. They wanted to put her in a nursing home near Chatham where I wouldn’t be able to visit her. And I got so frustrated I said, ‘Well, Don Fulton is my lawyer. He will be in touch with you regarding this matter.’ ‘Oh, he’s got a lawyer behind him.’ A week later: ‘Oh, we’ve found an opening.’ It goes that way. It goes that way in all segments of society. It shouldn’t.

Now, a friend of mine, my best friend, Paul McKenzie, obstetrician and gynecologist, I mentioned him early on, was dealing with people. He’s travelled all over the world, helping people, helping midwives and so on. Worldwide, in Africa, in Malaysia and so on. And in some of these countries, bribery is the accepted thing. ‘Hey can I do... five dollar bill, I just put it over there, just let me talk...’ ‘Oh, yeah. I think I can do...’ You know, it’s expected. If you don’t do it, you don’t get anywhere. And he was disgusted with that. But it hurt him and he had to do it. You play the game.

For example, he needed a telephone. He had to have a telephone. The waiting list was six months to a year for a telephone. He had to have that telephone. Fifty bucks or whatever. ‘We’ll see what we can do.’ And he got a telephone in a weeks time or whatever. I mean, we’re fortunate; we don’t have that. But a friend of mine, a good friend, he had a fifty dollar bill in his driver’s license. Stopped for speeding. ‘Driver’s license, please? Well, see now you were going so many kilometers over the speed limit.’ Takes the fifty dollars, puts it in his pocket, says, ‘Well, OK you’re lucky this time. Don’t speed.’ I mean if this guy, if my friend had been undercover, this cop would have been demoted at least. But, that was there for that purpose, and the guy knew the purpose, and the cop takes the fifty. So it happens here. It happens everywhere.

KH: Do you vote?

RM: Not only do I vote, but I have a perfect voting record. Municipal, provincial, federal.

KH: In other words, you’ve always voted for the person who would win?

RM: No, I’ve never not voted. I’ve always voted. No, not for the person who won. I’ve voted NDP and they haven’t won. Well, some of them have. I’m just saying, I have a perfect voting record and I take it very seriously. On the other hand, people say, ‘Don’t vote. It just encourages the bastards.’

KH: Well, there’s a certain idea, not without ground, that democracy as we know it is a joke, and so why participate if you don’t have any influence?

RM: Yeah.

KH: And yet you have?

RM: Yeah, but I know people who say just the opposite. Who say that’s what the authorities want. Don’t vote? They want that. Because then the worst bastards will get in. I vote, often I vote against. I would vote against Harper, not for this particular person. You know, stop the bastard. *mockingly tremulous* Oh, am I on tape? Oh, no. They’ll be after me! They’ll be after me!

SB: *laughing*

RM: One year I was seriously thinking of running for mayor. This was a number of years ago. A lot of people suggested that I run for mayor, and, if I did, I wasn’t just going to run as a fringe candidate, get five hundred votes and then, you know. No, I was really going to fight hard and have my proposals and so on. And I had backers, willing to back me with some money. And it takes big money behind you to get advertising, posters and so on. And I realized at a certain point that if they ever thought that I might win, they would stop me. They would put money against me, they would discredit me, because they couldn’t allow that to happen. I’d be so into anti-development, and so on. I couldn’t be elected. So I decided not to [run].

SB: You were probably right.

RM: But I’ve had many experiences in my life when I’ve been really targeted because I was a spokesperson for certain things and was discredited for that by different people. And I’ll just leave it at that. I won’t go into detail for various reasons. But you talk about fame, well, that’s the negative side of being well known. You get targeted for certain things. And people have asked me, ‘will you be a spokesperson for this or that? Will you speak?’ And, you know, I’m just in the background. In a life or death situation, if something was really important, I’d stand up. But I’m just going to be in the background, you know.

-

On Publication

KH: We were talking a bit about the world of money, and I was wondering lately about the idea of publication. It’s often been said that a writer is not the best judge of his or her own work, but, too, that an editor doesn’t necessarily have to take away anything from a poem. What do you think of the world of publication? Do you think it’s a selling-out thing? Does it cheapen the material if it’s edited to turn it into a product?

RM: No, I think that most of the great poets that I’ve met, that I’ve got to talk to, that have written about poetry, will have other poets who they respect read over their poem. Not, ‘What do the people out there think?’ No: ‘What does so and so think? This person is a really good poet, a really acknowledged poet. Can you give me some criticism.’ I’m not going to take it to anyone and ask, ‘Oh, what do you think of this?’ No. Do you see what I mean?

Trust. You trust certain people, or maybe just one person. Now, I was fortunate enough when I got published - I’ve been in small magazines all over the place, here and there over the years - and my journal was published, my first journal, before my poetry book, as was Pocketman, the book written about me. So my publisher and others knew there was a market out there for my writings. I mean, publishers, even really, really good ones are – my publisher, who was my best friend, Winston Shell, [he] and his wife, they’re very good friends of mine, but he was in it – it’s a business. People said, ‘Oh, he just published your book because you’re his good friend.’ No, no, no. He said himself he wasn’t running a charity. He just wants to make some money. And, plus, he thought what I did was good and would sell. So, it isn’t just one thing or the other. And even at that point I had a reputation in the sense that people knew who I was.

_

On War

KH: One of the criticisms of war is that it’s young men going to fight old men’s -

RM: Sure, sure, sure. I’d say it’s a game, you know, all the excuses for war. And then the idea, ‘Is it a just war?’ The concept of a just war. Again, it’s in every country. Canada: Wolfe and Montcalm fighting on the Plains of Abraham over the future of Canada. Is it gonna be French or is it gonna be British? And then the War of 1812 and so on. We talk about being a country with no war. Well, the Americans with the civil war, you know. Again, I could talk for hours about war. And by the way, have you read the war poets? These poets who went to war like Rupert Brooke, Sassoon, uh...

KH: Siegfried Sassoon.

RM: And... Owen... Wilfred Owen. And our Canadian guy, McCray. In Flanders Fields. You know, talking about patriotism and talking about Owen and Sassoon, [I think of] the terrible, terrible conditions... They were going through in the first world war and so on. These were the war poets. But again, you could do a patriotic song about war or fighting, or you can stand up against it and say how terrible it was. But generally, they’re important because they give a feeling: ‘What was it like to be in the trenches. What was it like to be there at this or that historical event?’

-

On Humour

KH: Do you think there’s any merit to the idea that poetry is a certain way in which to show off one’s feathers, one’s ability with language, one’s depth of emotion or ability to memorize and recite poetry?

RM: Oh, sure. Sure.

KH: How high in terms of importance would you rate that impulse as compared to, say, a feeling of solidarity or the importance of familiarizing others with language. In other words, how deep do you think that biological impulse goes?

RM: I think back to my days of high school and there were the jocks. They were the stars with women. But so were the musicians, the trumpet players in the bands. The actors were big, too. Now, how I was able to distinguish myself was by being the school clown, the class clown. So I developed my repertoire of jokes and humour. And that served me well all my life. And even in my drinking days, from some of the things I would pull, from some of the things I would do, humour saved me every time from being beaten up or badly beaten up or hurt. And I, by the way, place humour on a very, very high level. Humour, comedy, laughter, smiles, playfulness. Extremely important and tending to be underrated. And that’s why I have one whole poem, the poem I published, ‘The Answer Questioned,’ which you’ve read. It’s very funny. It’s serious as well. But it’s funny. It isn’t either one. Neither serious nor funny. It’s both. There’s punning there. I do psychological puns, literary puns, philosophical puns, corny puns, all together. And it’s something that nobody else has ever done, a book of one long pun poem.

KH: So, did you undertake that to create something amusing, something profound?

RM: All of the above. And I’ve always loved puns. I’m a punster. I like that great statement made by Marshall McLuhan: ‘Oh, but a man’s reach should exceed his grasp, or what’s a meta for?’

THE EVENT

WHERE: The Mykonos Restaurant at 572 Adelaide St. North, London, Ontario. The restaurant has a large, covered terrace just behind the main restaurant, which comfortably holds 60 poetry lovers. Mediterranean food and drinks are available. Except for the coldest months, the terrace is open to the parking lot behind. Overflow parking is available across the side street and in the large lot one block north, in front of Trad’s Furniture.

WHEN: Wednesday, October 1st, 2014

LIVE MUSIC: Jef-something Brian Thomas Ormston will open the event at 6:30. He will also perform during the intermission and at the end of the event.

THE FEATURED POET: Roy McDonald will open the poetry portion of the event at 7:00, followed by a Q&A.

OPEN MIC: Following the featured poet, 15 open mic poets will read for about 1.5 hours, ending about 9:00 pm. Each poet has five minutes (which is about two good pages of poetry, but it should be timed at home). Sign up on the reader`s list, which is on the book table at the back. It's first come, first served.

RAFFLE PRIZES: Anyone who donates to London Open Mic Poetry Night receives a ticket for a raffle prize, three of which will be picked after the intermission. The prizes consist of poetry books donated by Brick Books and The Ontario Poetry Society. Donations are our only source of income. We still haven't paid off our initial debt!

Roy was born in London in 1937 to the tuning of global war drums. He has since been an active member of the demonstrative community: he participated in the call for universal civil rights, environmental awareness and an end to the southeast Asian bloodbath of the 1960’s and 70‘s, and, more recently, denounced and supported the American invasion of Iraq in 2003 and the Occupy movement of 2011, respectively.

1970 met Roy with the publication of his poem “The Answer Questioned”, a stream of idiosyncratic puns which found the January edition of 20 Cents Magazine; it was reprinted and bound in 1979 by ERGO Productions and twice since by Conestoga Press. In 1978, ERGO productions again favoured Roy with the publication of “Living: A London Journal”. In 1979, Don Bell’s “Pocketman”, a novel which loosely follows Roy’s “wanderings and exploits”, was published by Dorset Publishing. A play about Roy’s life entitled “Beard”, written by Jason Rip, found the ARTS Project theatre in 2012 under the direction of Adam Corrigan Holowitz. After decades of transience, including residence in Montréal and Rochdale College in Toronto, all the while comforting the disturbed and disturbing the comfortable, Roy presently lives in his childhood home in London, Ontario.

The Interview

(Interview by Kevin Heslop for London Open Mic Poetry Night)

Despite the fact that this interview – originally an eight-thousand word transcript – has been segmented into themes, it retains the linearity of the conversation between Roy, Stan, and I. Roy’s words have been reproduced in their original form with some minor, faithful sculpturing in the interest of clarity. Put another way, the following consists of the two fillets of a single tuna, cubed raw. K.H.

On Writing

KH: Do you feel any obligation, speaking specifically of poetry, to your reader? Or do you write solely for yourself?

RM: I think a writer writes for both. There are different ways of writing, different reasons people write poetry or anything else. If we talk about poetry, it’s a way of thinking, a way of therapy. It can be very good therapy. You know, someone breaks up with one’s girlfriend or one’s girlfriend breaks up with you, and then you write a poem about the heartache. It helps. To write about the relationship can be very helpful. And another reason, of course, is memory. When I recite a poem... There’s a whole different feeling when one recites a poem than when one just reads a poem.

And [at] most poetry readings, people read their poems. I’ve made it a point to memorize a lot of my poems, and that just makes it easier to get directly to the other person because you’re not just reading it from a sheet of paper or a book. And if I’ve had certain memorable experiences, I write about them, and then when I read them to myself, to others, to an audience, to one person, to a group, the feelings come back that I wrote the experience about. And that’s valuable too.

KH: What do you think about structure in poetry? Meter. Form. Is it important? Is human communication through poetry best when structured, metered, and rhymed?

RM: Well, you know, that’s how it used to be in the oral cultures. With all that structure, poems are easily remembered because they’re rhyme schemes and so on throughout the centuries. And now we don’t need that. Denise Levertov. Have you ever heard of her?

KH: No.

RM: British-Russian background. Wonderful poet. She was an activist poet as well, as Margaret Atwood is. I really admire that in a poet. As is Robert Bly. Opposing the war in Viet Nam... [But] Denise Levertov talks about organic structure. It’s as you write it; it’s as your thought, your breath, your own individual way of doing it. And that’s what I do. I don’t start worrying about rhyme scheme and so on, anything like that. And people say what I’ve written ‘is just prose. That isn’t poetry.’ And I don’t c-, you know. Call it prose, you know. I call it poetry. A key thing about having something written as poetry is the lines, rather than the paragraphs. You know, like the right hand margin?

KH: OK.

RM: OK. And prose is written right to the end of each sentence, right? With poetry you have the white space around it?

KH: Mhm.

RM: Well, the white space in the lines, the way poetry is structured in stanzas, indicates pauses and helps you pause. And, rather than rushing through a statement – I’ll read political things, I’ll just rush right through... Poetry, partly because of the structure, slows you down and makes you... contemplative.

-

On Friendship

Did I tell you about the anecdote about how when I met Leonard Cohen, reciting one of his poems to him?

KH: Go ahead.

RM: Well, I met Leonard Cohen in Montréal in a bar called the Winston Churchill. And I sat with him, with a group, a small group of people. We were talking. And about half an hour after I’d met him I told him how I recited a poem that he wrote at a friend’s wedding ‘cause she liked the poem so much she wanted me to recite it at her wedding, and I did. And he said, ‘What poem was that?’ And I said, ‘It’s called “Song.”’ And he said, ‘”Song?” What’s that?’ He’d forgotten, or he didn’t; you know, you write a lot of poetry. ‘Song,’ he didn’t remember, and he didn’t know what I was referring to and so I said, ‘Well, I can recite it for you if you like.’ And I did and this is it:

Song

I almost went to bed

without remembering

the four white violets

I put in the button-hole

of your green sweater

and how I kissed you then

and you kissed me

shy as though I’d

never been your lover.

And at that point – beautiful poem – at that point we’re sitting around a table like this, and he gives me a hug. Now, I’d met him half an hour earlier and he gives me a hug. And I said, ‘Wow,’ you know. ‘What’s that for? Because you couldn’t remember the poem?’ And he said ‘No, the way you recited the poem brought back to my mind the experience I wrote the poem about and for that I am appreciative.’

Now that meant a lot to me. When a person is a poet you admire and if a person remembers your poetry so well they can recite it, even one poem – I’ve found that myself – that means a lot.

And I’ve done that with other poets as well. I’ve made it a point to. I know maybe about at least a hundred poems by heart. Several of mine, but those of Keats, Shelley, Wordsworth, Blake, Canadian writers, American writers, British writers, modern writers, and they come in handy to me when I’m going through certain experiences. And, because they’re in my head, I don’t have to have any paper, any books. I can just recite them like I could the poem that I recited that Leonard Cohen wrote.

-

On Self, Personal Influences and the Arts

KH: You mentioned [when we last spoke] that you’re a Jungian, or if you prefer, that Jung is the psychoanalyst with whom you most identify. I’m curious as to who else has shaped your philosophical foundation, say, or your sense of self? People you’ve known, or who have lived, with whom you most identify?

RM: Well, I did mention before Roberto Assagioli, the founder of psychosynthesis. It’s a whole psychological system and I am a qualified psychotherapist as a psychosynthesist-psychotherapist. Roberto Assagioli was a Venetian born in Venice. The worldwide center of psychosynthesis is in Florence. It’s a beautiful system that includes the Spiritual in the broadest sense, as does Jungian psychotherapy. And I’m into the Spiritual in the broadest sense. Again, the Spiritual...

KH: As different from the religious.

RM: Yeah. That’s an important distinction. I think that we are all spiritual beings. We’re not earthly beings having a spiritual experience; we are spiritual beings having an earthly experience.

KH: What do you think about the idea of soul?

RM: *slightly exasperated sigh*

KH: Or... are you a materialist, in other words?

RM: No. I’m an anti-reductionist and a non-materialist. In other words, you know the concept that our thoughts, our minds, are just epiphenomenon of the brain? I don’t believe that at all.

KH: What do you think our thoughts are, then?

RM: Well, the concept that I hold to is that we are part of a soul, a universal soul. Everything is tied together. And even quantum mechanics, quantum physics, tells you that. We’re all interdependent. We couldn’t last for five minutes if it wasn’t for the air around us. And the air around us is exchanging molecules from you and I and from other people and so on. We are beings in the environment. We can’t last without the grass, without the trees, without the animals.

KH: But that doesn’t necessarily mean that thoughts aren’t material.

RM: Again, what is material? When you get back to energy, it’s all energy. We live in an energetic universe. That this *indicating a chair* can be turned into energy or back into matter. We are not just our brains and our bodies. I’ll put it that way. We are much beyond that.

I like the concept that we are ‘not just our skin-encapsulated egos.’ Alan Watts used that term. I like it. It’s a very good term. I’m not just what’s inside here. I’m part of all of this. As Tennyson said in Ulysses, ‘I am a part of all that I have met.’ And Walt Whitman makes the same kind of comment, as did Richard Maurice Bucke, another person that I admire. I mean, people I admire, you know I could go on for an hour about different people that I admire, including poets. I think poetry should be a part of the furniture of one’s mind.

KH: That’s a fine phrase.

RM: You like that? Yeah. Being able to call on poetry. And art as well. I’m a lover and appreciator of art, good art. From the ancient cave paintings to the modern work of... modern Canadian and American painters. People like Greg Curnoe, Jack Chambers. These are London-area painters. Emily Carr. The Group of Seven. The arts are incredibly important. And yet, we know what’s happening with funding, eh? The arts are the first to go because they’re frills. People consider them as airy-fairy stuff... Well, what do we remember of past civilizations? Do we remember the millionaires and the rich people, or do we remember poets and writers and artists?

KH: But, I guess one of the arguments that could be made against art – just to entertain the thought – that could sort of relegate it to the fringe in terms of funding, would be that it’s not as functional as, say, a bridge or a repaired road.

RM: Yeah, but you see, to me it is not either/or. That’s the mistake that people make. Are you going to put the money into art and culture or into things like hospitals and things that that are needed. We need both. You know the statement, and it’s a good one: Jesus [said] ‘Man does not live by bread alone.’

-

RM: I’m very much into a concept and approach, and this is not original by any means, of Inner-Companions. And since we’re talking about poetry, poets and poetry and poems as Inner-companions. And I think of this when I think of a favourite poem of mine that’s inspired me. And I think of, say, a poem by Walt Whitman. I think of Walt Whitman. I think of him as a person. I think about how he was here in London visiting Richard Maurice Bucke in the London Psychiatric Hospital. I think of poets I know. When I read a poem by Margaret Atwood I can remember first meeting her, talking to her. Same with Leonard Cohen poems. [with] F.R. Scott who died a number of years ago. F.R. Scott, Frank Scott, wrote a wonderful poem called ‘To Anthia’:

When I no more shall feel the sun

Nor taste the salt brine on my lips;

When one to me are stinging whips

And rose leaves falling one by one,

I shall forget your little ears,

your crisp hair and your violet eyes

and all your kisses and your tears

will be as futile as your lies.

Now, when I met Frank Scott, I recited that poem to him. And again, we were talking earlier about how you recite a poem that you’ve memorized to a favourite poet and... it’s such a wonderful feeling. And I’ve had that, when people have memorized poems of mine and can recite them back to me. And I did that with Alden Nowlan as well. You know Alden Nowlan?

KH: No.

RM: New Brunswick poet. Underrated. Written something like 20 books of poetry. One of the best Canadian poets of the last century. He died relatively young, I think in his fifties. He was pretty young, but he was a great, great poet. And I met him, talked to him. And I’ll just recite one more poem.

To Nancy

Nancy, I’ve looked all over hell for you.

Nancy, I’ve been afraid that I’d die before I found you.

But there’s always been some mistake:

A broken streetlight, too much rum,

Or merely my wanting too much for it to be her.

Do read Alden Nowlan, you know, if you get a chance.

-

On Vice

KH: You know, the word rum came up in the poem and maybe it’s too general but what is the apparent draw towards vice? Artists traditionally, historically, have been drawn towards vice, and I was wondering if you had an opinion as to why.

RM: I disagree with your premise. Maybe you need to articulate more what you’re...

KH: Say, Kerouac was an alcoholic. Bukowski was an alcoholic. Ginsberg smoked cigarettes for much of his life. William S. Burroughs was a junky for a lot of his life. Say, Rimbaud, coming out of the opium dream...

RM: Well, a great many of these people, as you know, destroyed themselves. And, sooner or later – Rimbaud stopped writing poetry when he was 19 or 20. You burn out. Live fast, love hard, die young? OK, if you want to go that route. I don’t. And most of the world’s greatest poets didn’t. Including, uh, Walt Whitman wasn’t an addict...

Stan Burfield: You definitely can speak from that point of view, can’t you, because you’ve lived a lot longer than any of those people.

RM: And I’ve been there. I’ve been there.

SB: Oh, that’s right, yeah.

RM: I’ve been there. Don’t forget that. I talked about that [last time we spoke], that I was severely mentally ill for a number of years, for quite a few years, almost dying as a consequence of my mental illness. My mental illness was alcoholism. That is a mental illness. It’s named as such.

KH: Do you think that there’s any truth to the idea that there are certain substances which allow you to tap into a higher consciousness that you would otherwise have allowed to go unnoticed should you remain sober? LSD, for example, has been said to open your mind to -

RM: Yeah. But again, when you’re talking about drugs, there’s a great differentiation between the opiates, alcohol and other kinds of drugs and the psychedelics. So, we need to be very careful about what we’re talking about here. Yeah. Ayahuasca, LSD, psilocybin, peyote. Some of these can definitely open you up.

KH: Have you got an opinion on why there has been, at least in modern, Western civilization, a War on Drugs, as it’s called, why the ban of these substances which seem to be able to expand consciousness?

RM: Well, the powers that be don’t want that, obviously, because what would happen if everyone started thinking for themselves?

KH: Do you think that’s a conscious decision rather than an avoidance of...

RM: I think it’s that, and I think it’s the fact that the alcohol lobbies are tremendously important. Do they want people smoking up? I’ve been to parties at Western and so forth. It used to be, at the Homecoming weekend, people were so drunk and fights and so on. And I’ve been at Woodstock where hardly anybody drank. A lot of people smoked up and it was a very peaceful scene, right? The difference between those drugs, for example. And there’s obviously a danger with these things, with mind expansion. I took morning glory seeds...

KH: LSA...

RM: It’s similar to LSD. I had a whole heaven, hell, rebirth experience. And it was so scary that afterwards I had flashbacks. Never again. I never touched anything like that again, mushrooms, anything. And yet I continued drinking and that was what was killing me. That’s the interesting thing. I was stupid. I didn’t know any better. And I drank alcohol for many reasons. It was an all-purpose drug for me. I felt sad. I drank. I felt a bit better. I felt really anxious, a few drinks, ah, I felt better. I was very shy. I’ve always been a shy person, very much an introvert. We’ve talked about that. If I was sitting here sober and there was a beautiful woman sitting over there and I wanted to meet her, I would never think about going over and introducing myself because, ‘Oh, she’s probably busy or waiting for her boyfriend or whatever.’ A couple of beers in me and I’d go over and introduce myself. A couple of more beers, I’d introduce myself and start hugging her. A couple of more beers, I’d be feeling her up. And a couple of more beers, if she was with a guy, I’d tell the guy to f-off and then start caressing her. It’s a wonder that I’m still alive, you know? I mean, really, it is.

-

KH: If you were to choose one thing that you’re most proud of, that you’ve done or that you’ve participated in, could you narrow it down?

RM: Yeah.

KH: What would it be?

RM: Attaining sobriety! Stopping drinking.

SB: Why are you so proud of that?

RM: Because I was finally able to do it, and if I hadn’t done it, I would have destroyed myself. I’d be dead now. I wouldn’t be here. And it was difficult. As I said, alcohol is an all-purpose drug. If I felt sad, I would drink. If I felt happy, if I felt good, a few drinks and I’d be flying. And then the depression sets it. But really, it’s an all-purpose drug.

I was under the illusion that I couldn’t get through my days and nights without alcohol. It was that much of a crutch. And it was a rubber crutch. As I found out later, I could. I could get through without it. But I went through some very difficult times after I stopped drinking, but I’ve never had a relapse, fortunately. Very fortunately, because a lot of people do relapse and fall of the wagon.

SB: Yeah, some strong streak in you. Some determined...

RM: Yeah, but also feeling, ‘If I don’t, I’m gonna die.’ When you really face death, looking at you in the face, there’s death: do I want to live or do I wanna die. When you face that, it’s very scary. But it’s pretty sobering, too. And also, memory is very important to me. Jack Kerouac was called ‘memory babe’. That was his nickname because he had an incredible memory. And I have a very good memory as well. But, again, when Kerouac would drink more and more, you know, it screws up your memory! And I didn’t like the fact that I’d be out drinking, and I’d go out to the bar that I drank at the night before, and they’d say ‘Get out of here McDonald, you’re barred.’ ‘Why?’ ‘After what you did last night?’ ‘What’d I do last night?’ ‘Oh, come on. You know what you did.’ ‘Oh, no, I did? Oh, no...’ And so it went. And I did want to remember but I’d brown out, you know, when you remember just bits and pieces? And then black out. What? What happened? And you know, waking up in jail and wondering, how did I get here? What’s the charge? I mean, when you’re thrown in at night. What’s it gonna be? Drunk, or assault, did I hit a cop? I didn’t know. Scary, very, very scary. And again cops could have said I was pugnacious and I hit him. Assault. That’s assaulting a police officer. And it was never that, it was always drunk in a public place. And then it was a 30 dollar fine or 30 days in jail. Drunk and disorderly, it was called...

But Ginsberg certainly wasn’t an alcoholic. He did drugs, but they all did. He died at 71 or 72 [70]. Or Ferlinghetti. Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s still going and he’s about 94 or 95, now. Met him as well. And these are treasured meetings with people. Talking to them about their craft is very important to me. And you know Ted Hughes? Britain’s poetry laureate. He was married to Sylvia Plath. And I’ve met two Nobel Prize winners in poetry: Joseph Brodsky, a Russian poet, and Derek Walcott, a West Indian poet.

-

On Public Image

KH: In your opinion, how is fame positive? How is it negative?

RM: Well, you gotta know how to use fame. It can benefit you, it can hurt you. I get people out there who – and this is not uncommon – who’ll say, ‘Look at this guy, look at his appearance. He’s just a bum, but poetry? Ah, fuck. He’s a loser. He’s an old man.’

I get a lot of abuse and a lot of it is just pure jealousy. I’m out on the street. I’m singing and hugging all kinds of beautiful women. Because I love women, you know. I mean who doesn’t? I guess there’s some that don’t, but I do. ‘So he’s got a couple of books published, so what? Big deal.’ Well, I don’t glory about the fact that I’ve got a couple of books published. I’m glad I have. I’m glad I’ve had a book written about me and a play written about me and so on. And I’m very high profile.

Well, it can be used for you, it can be used against you. I’ve had hassles, like the time I was thrown off the University of Western Ontario campus. I went immediately down to the [London Free Press], I knew people there. They wrote a story about it; I got right back on campus. I knew people at City Hall. I mean, it’s sad in this case, in this society, that if you know certain people. you can have power. You know certain people. Media people, mayors, provincial leaders. ‘Hey, I’ve got connections. Don’t screw me around or I’ll...’ And the poor guy or girl that’s on the street and doesn’t have any of these connections, they’re just nobody. They’re powerless...

When I was thrown off the [Western University] campus, the Chairman of the grounds at the time who issues the orders on the grounds because it’s a semi-private place, the guy who wrote – I can’t think of his name at the moment – an editorial in the Western Gazette on my being thrown off the campus, he asked the guy in charge of the grounds, ‘Does this sort of thing happen from time to time? You know, people come up there from the community who are not students, not teachers and get asked to leave...’ He said ‘Oh, yeah it happens all the time.’ ‘And what happens to them?’ ‘They go away. We never see them again.’ They’ve got no recourse. They’re just riff-raff of London going up to the country club of Western. You can detect a bit of anger, right?

KH: It is a private establishment though, technically, no?

RM: No. Technically it’s like a mall. You can be asked to leave a mall; you can’t be asked to leave the street or in a public place...

KH: Right, but a mall is private property, too, isn’t it? It’s accessible to the public, but it...

RM: No, this goes under the law with regards to schools. Now I can see, say, you or any of us hang around a high school. Obviously, what’s going on here?

KH: Right. Lecherous.

RM: Yeah. Now, with Western or Fanshawe you can be asked to leave with no reason given if you’re not a teacher or a student or a member of the support staff, like a cook, or if you’re working in the bookstore or whatever. You can be asked to leave. And what happens is that it’s open in the sense that there are venues there open to the public. The bookstore is open to the public. Not just the students; it’s open to the public. Events at the stadium are open to the public. Alumni Hall [holds concerts] that are open to the public. They want the public to come. On their terms.

And they lied when they threw me off the campus. They lied to the press when they said that I didn’t have any identification. They thought I was a vagrant. Total bullshit. Bureaucratic bullshit. They knew exactly who I was and why they wanted me off the campus. By the way, I had a whole wallet of identification. They blamed it on the university cops not knowing who I was. I showed them my books. When I get that kind of bullshit and people read the paper and say, ‘They didn’t know who you were.’ Bullshit. They knew exactly who I was. You see what I mean? I’ve dealt with bureaucracies in the past and I know what they can do, how they can screw people around in every way, on every level. Not that all bureaucrats are bastards, but a certain amount of them are. And far too many of them are uncaring, you know. ‘Who are you?’

Like you. Hey! Why are you wearing your hair like that? You’ve got a beard. I don’t like that hat. That hat looks kind of strange. What are you doing up here? You see? You could get that tomorrow. You could go up there and get that tomorrow.

KH: I know I’m privileged in that way.

RM: Why? Because you’re...

KH: Acceptable by society’s standards, more or less.

RM: Oh, more or less. You see, well, it’s just, how far out can you be? How far out am I? Would they ask him to leave? See, it’s not just they know who they’re asking to leave and why. They knew exactly who I was. They knew I was in the cafeteria. I’d get people to think. I’m very well known. They’ve written several stories about me in the [Western Gazette] over the years. They knew me. That and, plus, my appearance. ‘He doesn’t look like a student,’ you know.

-

On Politics

KH: Are there any barriers to communication in particular that stand out to you, or is it too complicated to...

RM: Well, it’s just a complex question. There’s all kinds of barriers to communication, language being one obvious one. And social class, being one. And we’re a classless society. Sure we are. Sure we are. We’re not as [stratified] as the British system.

KH: Does it come down to money?

RM: Money. Power. And they generally go together. Though, a person can have power and not much money; but if they’re in a powerful position, they have the power and they can change things. By the way, I’m 77. I’ve gone through so many things. I’ve seen so many things. And I had to deal with putting my father in Parkwood Hospital. And I had to deal with bureaucracy there. I had to put my aunt in hospital. She had dementia. My father had a stroke from which he never recovered. That’s why he had to be put in Parkwood. My aunt had dementia. She had to be put in a nursing home. And all the bureaucracy dealings that I went through: what I could do, what I couldn’t do, and what they said. Each case was different. With my aunt, they didn’t have an opening for her. They wanted to put her in a nursing home near Chatham where I wouldn’t be able to visit her. And I got so frustrated I said, ‘Well, Don Fulton is my lawyer. He will be in touch with you regarding this matter.’ ‘Oh, he’s got a lawyer behind him.’ A week later: ‘Oh, we’ve found an opening.’ It goes that way. It goes that way in all segments of society. It shouldn’t.

Now, a friend of mine, my best friend, Paul McKenzie, obstetrician and gynecologist, I mentioned him early on, was dealing with people. He’s travelled all over the world, helping people, helping midwives and so on. Worldwide, in Africa, in Malaysia and so on. And in some of these countries, bribery is the accepted thing. ‘Hey can I do... five dollar bill, I just put it over there, just let me talk...’ ‘Oh, yeah. I think I can do...’ You know, it’s expected. If you don’t do it, you don’t get anywhere. And he was disgusted with that. But it hurt him and he had to do it. You play the game.

For example, he needed a telephone. He had to have a telephone. The waiting list was six months to a year for a telephone. He had to have that telephone. Fifty bucks or whatever. ‘We’ll see what we can do.’ And he got a telephone in a weeks time or whatever. I mean, we’re fortunate; we don’t have that. But a friend of mine, a good friend, he had a fifty dollar bill in his driver’s license. Stopped for speeding. ‘Driver’s license, please? Well, see now you were going so many kilometers over the speed limit.’ Takes the fifty dollars, puts it in his pocket, says, ‘Well, OK you’re lucky this time. Don’t speed.’ I mean if this guy, if my friend had been undercover, this cop would have been demoted at least. But, that was there for that purpose, and the guy knew the purpose, and the cop takes the fifty. So it happens here. It happens everywhere.

KH: Do you vote?

RM: Not only do I vote, but I have a perfect voting record. Municipal, provincial, federal.

KH: In other words, you’ve always voted for the person who would win?

RM: No, I’ve never not voted. I’ve always voted. No, not for the person who won. I’ve voted NDP and they haven’t won. Well, some of them have. I’m just saying, I have a perfect voting record and I take it very seriously. On the other hand, people say, ‘Don’t vote. It just encourages the bastards.’

KH: Well, there’s a certain idea, not without ground, that democracy as we know it is a joke, and so why participate if you don’t have any influence?

RM: Yeah.

KH: And yet you have?

RM: Yeah, but I know people who say just the opposite. Who say that’s what the authorities want. Don’t vote? They want that. Because then the worst bastards will get in. I vote, often I vote against. I would vote against Harper, not for this particular person. You know, stop the bastard. *mockingly tremulous* Oh, am I on tape? Oh, no. They’ll be after me! They’ll be after me!

SB: *laughing*

RM: One year I was seriously thinking of running for mayor. This was a number of years ago. A lot of people suggested that I run for mayor, and, if I did, I wasn’t just going to run as a fringe candidate, get five hundred votes and then, you know. No, I was really going to fight hard and have my proposals and so on. And I had backers, willing to back me with some money. And it takes big money behind you to get advertising, posters and so on. And I realized at a certain point that if they ever thought that I might win, they would stop me. They would put money against me, they would discredit me, because they couldn’t allow that to happen. I’d be so into anti-development, and so on. I couldn’t be elected. So I decided not to [run].

SB: You were probably right.

RM: But I’ve had many experiences in my life when I’ve been really targeted because I was a spokesperson for certain things and was discredited for that by different people. And I’ll just leave it at that. I won’t go into detail for various reasons. But you talk about fame, well, that’s the negative side of being well known. You get targeted for certain things. And people have asked me, ‘will you be a spokesperson for this or that? Will you speak?’ And, you know, I’m just in the background. In a life or death situation, if something was really important, I’d stand up. But I’m just going to be in the background, you know.

-

On Publication

KH: We were talking a bit about the world of money, and I was wondering lately about the idea of publication. It’s often been said that a writer is not the best judge of his or her own work, but, too, that an editor doesn’t necessarily have to take away anything from a poem. What do you think of the world of publication? Do you think it’s a selling-out thing? Does it cheapen the material if it’s edited to turn it into a product?

RM: No, I think that most of the great poets that I’ve met, that I’ve got to talk to, that have written about poetry, will have other poets who they respect read over their poem. Not, ‘What do the people out there think?’ No: ‘What does so and so think? This person is a really good poet, a really acknowledged poet. Can you give me some criticism.’ I’m not going to take it to anyone and ask, ‘Oh, what do you think of this?’ No. Do you see what I mean?

Trust. You trust certain people, or maybe just one person. Now, I was fortunate enough when I got published - I’ve been in small magazines all over the place, here and there over the years - and my journal was published, my first journal, before my poetry book, as was Pocketman, the book written about me. So my publisher and others knew there was a market out there for my writings. I mean, publishers, even really, really good ones are – my publisher, who was my best friend, Winston Shell, [he] and his wife, they’re very good friends of mine, but he was in it – it’s a business. People said, ‘Oh, he just published your book because you’re his good friend.’ No, no, no. He said himself he wasn’t running a charity. He just wants to make some money. And, plus, he thought what I did was good and would sell. So, it isn’t just one thing or the other. And even at that point I had a reputation in the sense that people knew who I was.

_

On War

KH: One of the criticisms of war is that it’s young men going to fight old men’s -

RM: Sure, sure, sure. I’d say it’s a game, you know, all the excuses for war. And then the idea, ‘Is it a just war?’ The concept of a just war. Again, it’s in every country. Canada: Wolfe and Montcalm fighting on the Plains of Abraham over the future of Canada. Is it gonna be French or is it gonna be British? And then the War of 1812 and so on. We talk about being a country with no war. Well, the Americans with the civil war, you know. Again, I could talk for hours about war. And by the way, have you read the war poets? These poets who went to war like Rupert Brooke, Sassoon, uh...

KH: Siegfried Sassoon.

RM: And... Owen... Wilfred Owen. And our Canadian guy, McCray. In Flanders Fields. You know, talking about patriotism and talking about Owen and Sassoon, [I think of] the terrible, terrible conditions... They were going through in the first world war and so on. These were the war poets. But again, you could do a patriotic song about war or fighting, or you can stand up against it and say how terrible it was. But generally, they’re important because they give a feeling: ‘What was it like to be in the trenches. What was it like to be there at this or that historical event?’

-

On Humour

KH: Do you think there’s any merit to the idea that poetry is a certain way in which to show off one’s feathers, one’s ability with language, one’s depth of emotion or ability to memorize and recite poetry?

RM: Oh, sure. Sure.

KH: How high in terms of importance would you rate that impulse as compared to, say, a feeling of solidarity or the importance of familiarizing others with language. In other words, how deep do you think that biological impulse goes?

RM: I think back to my days of high school and there were the jocks. They were the stars with women. But so were the musicians, the trumpet players in the bands. The actors were big, too. Now, how I was able to distinguish myself was by being the school clown, the class clown. So I developed my repertoire of jokes and humour. And that served me well all my life. And even in my drinking days, from some of the things I would pull, from some of the things I would do, humour saved me every time from being beaten up or badly beaten up or hurt. And I, by the way, place humour on a very, very high level. Humour, comedy, laughter, smiles, playfulness. Extremely important and tending to be underrated. And that’s why I have one whole poem, the poem I published, ‘The Answer Questioned,’ which you’ve read. It’s very funny. It’s serious as well. But it’s funny. It isn’t either one. Neither serious nor funny. It’s both. There’s punning there. I do psychological puns, literary puns, philosophical puns, corny puns, all together. And it’s something that nobody else has ever done, a book of one long pun poem.

KH: So, did you undertake that to create something amusing, something profound?

RM: All of the above. And I’ve always loved puns. I’m a punster. I like that great statement made by Marshall McLuhan: ‘Oh, but a man’s reach should exceed his grasp, or what’s a meta for?’

THE EVENT

WHERE: The Mykonos Restaurant at 572 Adelaide St. North, London, Ontario. The restaurant has a large, covered terrace just behind the main restaurant, which comfortably holds 60 poetry lovers. Mediterranean food and drinks are available. Except for the coldest months, the terrace is open to the parking lot behind. Overflow parking is available across the side street and in the large lot one block north, in front of Trad’s Furniture.

WHEN: Wednesday, October 1st, 2014

LIVE MUSIC: Jef-something Brian Thomas Ormston will open the event at 6:30. He will also perform during the intermission and at the end of the event.

THE FEATURED POET: Roy McDonald will open the poetry portion of the event at 7:00, followed by a Q&A.

OPEN MIC: Following the featured poet, 15 open mic poets will read for about 1.5 hours, ending about 9:00 pm. Each poet has five minutes (which is about two good pages of poetry, but it should be timed at home). Sign up on the reader`s list, which is on the book table at the back. It's first come, first served.

RAFFLE PRIZES: Anyone who donates to London Open Mic Poetry Night receives a ticket for a raffle prize, three of which will be picked after the intermission. The prizes consist of poetry books donated by Brick Books and The Ontario Poetry Society. Donations are our only source of income. We still haven't paid off our initial debt!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed