You can find this book for $14.40 on Amazon.com or for £9.12 on Amazon.co.uk but – despite its Canadian content – not on Amazon.ca. My distant cousin-by-marriage Frank Sanderson created it as a self-published Amazon title. He’s a retired professor of Sports Science – in Canada that’s probably Kinesiology – who lives in Liverpool but whose ancestors lived and farmed for at least 4 centuries in or near the valley (“dale”) of the Wear River in County Durham.

The book itself is a contemporary example of the kind of technological change that in the late nineteenth century brought an end to traditional farming and social practices in British areas such as Weardale and spurred many disadvantaged inhabitants to emigrate to North America or Australia. A few decades ago such a book would have been a “local history,” produced in a village printshop and sold in local stores to residents and visitors. Today it is written, formatted to include more than 60 photos and maps and ‘typeset’ on the author’s computer and globally distributed – sometimes to descendants of those nineteenth-century emigrants.

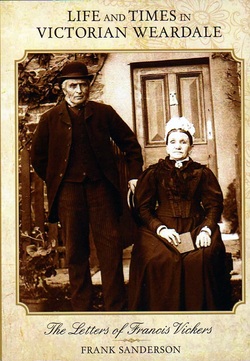

Sanderson has organized his book around eight letters sent by Francis Vickers (1821-1903), the son of his great-great grand uncle (i.e. Sanderson’s first cousin three-times removed) to his cousins George and Thomas Vickers who had emigrated to Canada. For each letter Sanderson writes a chapter in which he glosses the places, events and people mentioned by Vickers and contextualizes them within local, national and international economic and political history. Vickers writes the first letter in 1874 and the last in 1901. Much like Charles Olson recommended to Ed Dorn, Sanderson appears to have learned more about his subject – a few square miles of Weardale during a 27-year period – than anyone before him. And much like Olson's admiration for Gloucester fishers, his admiration for Weardale's

He portrays them as brave religious and political dissenters -- many of them members of the Primitive Methodist church and supporters of the then ‘leftist’ Liberal Party of Gladstone and Lloyd-George. His respect for his subjects often make him seem to share more with these pious and inevitably parochial people than he probably does.

Weardale in some ways during the nineteenth century was an unacknowleged social experiment. It was the site of the first railroad in the world, built by George Stephenson from Stockton to Darlington in 1825 and gradually extended northwestward to Stanhope, and to Wearhead by 1895. The railroad enlarged the horizons of the inhabitants from the distance which a horse-drawn cart could travel to the distances within most of the county of Durham – and eventually those within entire country. Marriages had traditionally been mostly between members of neighbouring farm families but were soon as often between partners from neighbouring and non-neighbouring counties. Farmers who had raised crops for local markets were now competing with farmers in North America. Their sons were training not to be farmers but to be mechanics, machinists, train operators and stationary engineers. Sanderson is particularly good at detailing and explaining these changes and their consequences.

This is Sanderson’s first book and it is a bit clunky in places, most noticeably when he needs to allude to an event that he has already narrated in an earlier chapter and repeats many of his earlier phrases – giving the book, probably unintentionally, a folksiness and lack of self-consciousness one might find in a small-town newspaper. But he definitely does succeed in his revisionist aim of acknowledging “the ordinary lives of ordinary people” that, “[a]longside the great events of history” formed “a parallel universe occupied by the vast majority of English people” (1).

FD

RSS Feed

RSS Feed