I write that I ‘browse’ through this volume because it is unlikely to be one that anyone can easily read through. The editors invited contributors to address any of the many areas that Barbara cared passionately about. No longer tied together by that passion, her wit, her knack for startlingly productive juxtapositions, her ability to make her own limitations the ground for an abruptly illuminating shift of context, the areas of her attention here drift apart into separate subject areas, no matter how sound the writers’ scholarship or incisive their analyses. Two of Barbara’s most important assets were her distractibility and her skill at analyzing her moments of distraction, asking why she had been distracted, what was the obscure connection between the two focuses – letting her investigations be informed by the unlikely rather than the obvious.

Many of the contributors are aware of being challenged by Barbara’s unorthodox routes toward insight, particularly the York University librarian, Lisa Sloniowski, who Barbara, shortly before her death, lured into becoming the curator

Barbara’s collection was large, loosely organized, and interspersed throughout her house. .... [H]er books were jammed full of notes and photocopies, and the papers of colleagues and students were tucked in-between them, connected in ways perhaps clear only to Barbara herself.

We tend to distinguish between books and papers in libraries and archives. We house them separately and have significantly different processes for arrangement and description. Barbara maintained no such institutional illusions, and in one glance her collection made visible and material the intertextual and the dialogic, as well as the historical palempsest of her own thinking. (326)

Barbara’s collection demands that we interrogate the particular archival practices posed by it and ask ourselves whether these seemingly logistical issues cast a unique light upon the hegemonic nature of our technologies of organization, access, and preservation. (328-9)

The question of what kind of memorial this book may be thus raises a number of thorny issues. One of these is one also raised by Sloniowsky – the question of whether one should memorialize a single individual rather than the network or networks which nourished her work. “This emphasis on the individual is particularly problematic when dealing with a collector who is understood to be a cultural and politically turning platform, a dissemination mechanism in a larger feminist community. [....] How does the archive collude in erasing communities and collectivity while rationalizing the subject” (335)? The four-person editorship and the numerous contributors who worked with Godard goes some distance here toward addressing that.

Another issue is that of “living memory” – how “public” is a $45 academic paperback that is already for sale at an international antiquarian book dealer for $113.59? Barbara herself preferred to present her work not in books but at conferences and in non-academic periodicals such as Fuse, Tessera, and Open Letter, and to avoid academic journals such as Canadian Literature which had sometimes edited out of her articles passages of theorizing and self-foregrounding which she had viewed as essential to her thesis. She preferred to publish her articles within weeks or months of writing them – while they were still “living” – rather than endure the months of vetting that most academic articles and books receive. These preferences caused her much grief from university committees who routinely rewarded those who published in ‘refereed’ books and journals. As her department chair in the 1980s I advised Barbara to publish a collection of her essays – even volunteering to help her assemble them – but she preferred to spend her time writing new essays that addressed matters newly urgent. Those matters, and the social or public policy changes they required, were more important to her than the individual rewards that a book or refereed article might bring to her from a university salary, promotion or appointments committee. Most of the academic contributors to this volume have, not surprisingly, published more books than Godard. The TransCanada series, despite its beginnings in a 2005 Simon Fraser University conference launched in a flurry of “turning point” and “crisis” rhetoric, has quickly become a mainstream institution, with its co-founder now the Avie Bennett Chair in Canadian Literature at the University of Toronto. These are valuable contexts that Barbara was quite capable of working within but not among the ones in which she made her most significant culture-changing contributions.

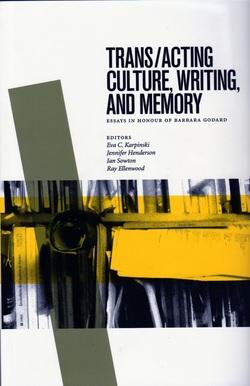

The introduction to Trans/acting Culture, Writing, and Memory, by Eva C. Karpinski and Jennifer Henderson, is almost a Godardian piece of writing. They set out to comment on each of the contributions but in doing so keep returning to Godard’s own work and thus create a portrait of her career that is extensive, fragmented, and subtle. Also of general interest to those who knew or were influenced by Barbara is the lead-off essay, Danielle Fuller’s “Reader at Work: An Appreciation of Barbara Godard.” Fuller explores and responds to a selection of Godard essays, creating a collage that has structural resemblances to many of them. She offers excellent summaries of their concerns which one hopes will be as much a gateway back to Barbara’s work as a "prolegomenon" to this collection. Her essay indirectly reminds readers that many of Godard’s most important essays are still uncollected and difficult to access.

FD

RSS Feed

RSS Feed