Thirty years ago I presented a paper at McGill in which I lamented that term for its apparent linearity, like an army on the march, and quoted Baudelaire’s mistrust of its overt militarism. Perloff here offers a strong case for retaining both it and its category, positing a historical avant-garde that began in Europe in the latter part of the nineteenth century and which developed until approximately 1916 when it began to be overwhelmed by the Great War, the Depression, the Second World War, the Cold War and the conservative expressive poetics all four events encouraged. The recovery of that avant-garde, and the creation of new poetries built on its methods of appropriation, quotation, collage and montage, are what she finds to be simultaneously both avant-garde and arrière-garde today. A military avant-garde usually has an accompanying arrière-garde, she points out, writing “[w]hen an avant-garde movement is no longer a novelty, it is the role of the arrière-garde to complete its mission, to ensure its success. The term arrière-garde, then, is synonymous neither with reaction nor with nostalgia for a lost and more desirable artistic era; it is, on the contrary, the 'hidden face of modernity' (Marx 6)" (53).

She declines the association of “progress” with both “avant-garde” or any intellectual movement, including the ethical progress often claimed for literature by post-colonial theorists (in Canada see Diana Brydon in “Canada and Postcolonialism” 64 and Pauline Butling in Writing in Our Time 122), implying that the most that literature can aim to accomplish socially is to be formally relevant to its cultural moment (53).

“Only the copied text commands the soul of him who is occupied with it, whereas the mere reader never discovers the new aspects of his inner self that are opened by the text.” These words anticipate in an uncanny way the turn writing would take in the twenty-first century, now that the Internet has made copyists, recyclers, transcribers, collators, and reframers of us all. Benjamin’s Passage becomes the digital passages we take through websites and Youtube videos, navigating our way from one Google link to another and over the bridges provided by our favorite search engines and web pages. In this new arcade world, writing a poem is no easier than it ever was. Just different. (49)

Here is the important distinction between avant- and arrière-garde. The original avant-garde was committed not to recovery but discovery, and it insisted that the aesthetic of its predecessors – say, of the poets and artists of the 1890s – was “finished.” But by midcentury the situation was very different. Because the original avant-gardes had never really been absorbed into the artistic and literary mainstream, the “postmodern” demand for total rupture was always illusory. (67)

Perloff then examines five mostly conceptualist examples from US, British, and German contemporary writing that recover and redevelop the poetics of the first avant-garde – Charles Bernstein’s libretto for Brian Ferneyhough’s opera about Benjamin, Shadowtime (premiered 2004 in Munich), Susan Howe’s The Midnight, Caroline Bergvall’s installation Say: “Parsley,” Yoko Tawada’s Sprachpolizei und Spielpolyglotte and Kenneth Goldsmith’s Traffic. All are offered as examples of writing in the “new arcade world” of global migration and instant digital republishing – the German-born French-Norwegian Bergvall lives in London and writes in English; the Japanese-born Tawada lives in Berlin, writes in both German and Japanese, and has won the Goethe Medal.

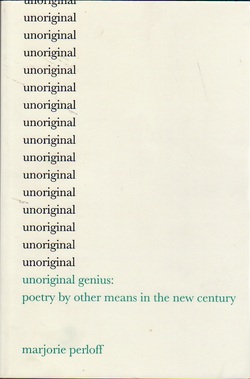

These chapters serve as proposed maps of the current avant-garde/arrière-garde activity, suggesting its global dimensions, and how that global, often internet-aided activity has been bringing to an evolutionary close the Language-poetry era in US poetry, dissolving the once stubbornly national boundaries of its concerns. She also shows how paradoxically complex and creative “unoriginal genius” must be. In her reading of Goldsmith’s Traffic, for example, she reveals how this self-proclaimed mere copyist has selectively shaped, edited even, his transcriptions of radio traffic reports. “Goldsmith’s ‘transcription’ is thus hardly passive recycling.” “... [T]he ‘plot’ ironically turns out to be a perfect Aristotelian one with beginning, middle, and end ...” (161). She warns a reader not to believe “that what Goldsmith says about a given work [i.e. that it is “unreadable,” or that it is a mere “mechanical transcription” of a time period, or that its “concept” is more important than its text] is equivalent to what it is” (149).

I can think of a few editors of literary presses who could profit from reading this book, and some book reviewers recently noted by Donato Mancini.

FD

RSS Feed

RSS Feed