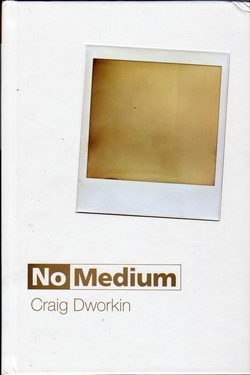

Craig Dworkin’s first criticism book, back in 2003, was Reading the Illegible, and focused on literary works that appropriated, rearranged or otherwise altered the texts of other writers. This new book – which, according to Amazon is going to be reissued in paperback next February – could have been titled “Reading the Absences.” Here Dworkin discusses book-format works that contain extensive lacunae – books that have a title, an author and sometimes preliminary pages but whose remaining pages are deliberately blank; books that have commentaries in their margins but whose principal text, the one commented upon, has been deliberately erased; books in which everything has been erased except its footnote numbers and the footnotes themselves; books in which only the footnotes have been created; books which reprint a vanished text and on various pages offer footnotes that explain some of the circumstances of the vanishing, or which print such a text along with its not-vanished indexes or bibliographic references; books which reproduce well-known works of visual art as the single colour produced when their colours have been digitized and averaged; books of photographs which have been altered by blackout and erasure; books and other works that have effectively vanished through being translated into other languages and media. So to some extent, then, No Medium extends Dworkin’s discussions in Reading the Illegible.

Erasures obliterate, but they also reveal; omissions within a system permit other elements to appear

all the more clearly. (9)

Dworkin’s critical approach here is mostly that of a bibliographer – he accumulates, classifies, describes, and compares, without evaluating, the writing and art practices of numbers of people whose work could benefit from a cataloguer’s help to reach a wider audience. Though American himself, his interests are mainly transnational, with many of the artists he focuses on being from western Europe and Japan, and many of the US ones being influenced by or working with non-US artists. This is an unusual approach, and a rather welcome one I would say, in US counter-hegemonic literary commentary.

I agree with him on that – the work he discusses, its history, and the aesthetic issues it raises, ought to at the very least be known, if not admired, by anyone who writes or aspires to write.

FD

RSS Feed

RSS Feed