But in the context of the Kelowna summer institute which I recently attended, “Poetry On and Off the Page,” McGurl’s various mentions of literary tape recording have been standing out for me. One of these appears to be an error – he discusses the early 1930s work of Harvard classicist Millman Parry’s in recording Balkan oral storytelling as his having “traipsed about the Yugoslavian countryside recording the living vestiges of its ancient illiterate storytelling tradition on audiotape” (231). Harvard’s Parry collection indicates that Parry had used the recently developed aluminum recording disc. Magnetic audio tape, a much more accurate, portable, potentially marketable and less expensive medium, didn’t – as I mentioned in my previous post – become available outside of Germany until after the Second World War.

McGurl uses the work of Parry and his student Albert Lord in a chapter titled “Our Phonocentrism” to explain the rise of interest in the 1960s in the oral delivery and oral composition of poetry. In his 1960 book The Singer of Tales Lord had declared that the traditional “oral poem is not composed for but in performance” (231). Novelist Ken Kesey is recalled by fellow writer Ken Babbs to have aimed during their schoolbus-named-‘Further’ tour in 1964 to have aimed “to take acid and stay up all night and rap out novels and tape record them. Then we started talking about getting the movie cameras and filming it. So we were very swiftly going from a novel on a page to novels on audio-tape to novels on film” (211). McGurl includes both the Lord and Babbs quotations in explaining the 1960s quest for “vocal presence” in literature,

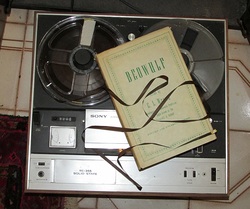

Certainly the tape recorder, coming into general use around 1959-60, had the potential to aid in the oral composition of eventually written texts, much the way Parry and Lord had imagined a long series of oral performances had once led to the written texts we know today as “Homer.” Olson’s 1948 “Projective Verse” essay, with its proposal (via Edward Dahlberg) that in poetry “one perception must immediately and directly lead to a further perception,” and that typewriter spacing could be used to preserve the immediacy of the oral pauses and stresses created during such a series of perceptions, was close to viewing the typewriter as an audio recording device, one that could be used to create an authentic “act of the instant” poem. Himself a self-trained classicist, Olson had owned a copy of Parry’s 1932 article “Studies in the Epic Technique of Oral Verse-making” and had purchased Lord’s book at publication (Maud , Charles Olson’s Reading 314). But perhaps it took the invention of magnetic recording tape and the reel-to-reel recorder to give Parry and Lord’s hypotheses and Olson’s theories about orality and authenticity-preserving composition significant impact.

As for McGurl, he has reservations about this kind of orality-based authenticity similar to those I expressed back in 1988 in Reading Canadian Reading: that there is little way of knowing whether it has been consciously or unconsciously faked (McGurl’s word is “staged”) and that – like Homeric verse itself – it can lead to mannerisms and formulae, as one finds in Al Purdy’s later verse. A writer can master methods for sounding spontaneous and authentic. McGurl goes so far as to suggests that in US fiction and its Creative Writing programs there was an unlikely alliance between the much older New Criticism concern with craft (cf my post on Donato Mancini's recent book) and the new 1960s desire for the appearance of “experiential authenticity” (230), one which led to the widespread, and often derided, Creative Writing class instruction to “find your voice.”

The latter, particularly in the context of finding one’s voice “as ethnic or racially marked subjects,” became the focus of linguist Walter Ong, teacher Albert Guerard and novelist John Hawkes in “the Voice Project,” in which writing students, McGurl reports,

were sent out with tape recorders to collect and listen to “original folklore from their parents, from other students

in dormitories, from unlikely places in the community – such as a junkyard in East Palo Alto.” Listening to these

tapes, students would in theory learn to appreciate the vivacity of everyday storytelling and, set free from the

“rationalistic approaches to writing” usually foisted upon freshmen, would try to emulate it in their own assign-

ments. ...[T]he recording technology used in the Voice Project’s Palo Alto folkloric activity was ... put to the

purposes of generating self-reflexive feedback in the classroom, thus to make the student as writer coincide with

writer as speaker. (255, with quotations from the project report by Hawkes et al).

McGurl comments dryly that “the application of recording technology to composition instruction can be seen as only supplementing the externalization of intellectual activity intrinsic to all classroom teaching, where the ‘technology’ is the institutional form itself” (256).

FD

RSS Feed

RSS Feed