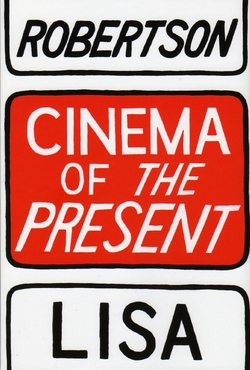

“Cinema of the Present” would be an appropriate title for many recent conceptual poetry books, including Fitterman’s No, Wait. Yep. Definitely Still Hate Myself, with its assemblage of approximate 1000 on-line expressions of self-doubt, which I looked at here last week. Would Fitterman’s be an adequate title for the Robertson? – not quite, but close. But change his “hate” to “doubt” and we’d be there. Robertson’s title, however, makes a much larger claim to profundity and cultural relevance than does Fitterman’s, or than, say, Peter Jaeger’s also similar subjectivity-mapping long conceptual poem The Persons.

In a generally helpful discussion of Cinema of the Present, reviewer Alex Crowley in Publishers Weekly writes, rather paradoxically, that it “defies review,” – that it “instead demand[s] engagement, conversation, and multiple rereads,” and that [i]t may not be a great place to start for newcomers to Robertson’s work.” That her poetry is pleasurably incomprehensible seems to be becoming a standard view of Robertson – most of the online bookstores offering the book quote a New York Times review of her 2009 Magenta Soul Whip that “Robertson proves hard to explain but easy to enjoy” – a quotation that also appears on her publisher’s website. Though to some it may recall Swinburne, it’s probably a powerful marketing tag, since most readers of traditional poetry by far prefer enjoyment to explanation. Moreover Cinema of the Present isn’t all that far from traditional poetry (while still far from Swinburne) – much of it can be read as disguised lyricism or confessionalism, or even as forming a disguised romantic ode. In such a reading it may be not at all difficult for newcomers.

Crowley also describes Robertson not as Canadian but as “Canadian-born” and “living in France.” Perhaps being Canadian is not an especially attractive attribute to Publishers Weekly readers, who tend to be connected to US publishing and bookselling – better to have that citizenship in doubt. Perhaps he hopes that “Canadian-born”

Many writers may find Cinema of the Present engaging less because of its many fragmentary yet exquisite moments of painful doubt than for the surprises offered by its obviously shaped structure. Its montage of questions and statements gradually changes in tone and emphasis – thus side-stepping the homogeneity of tone and content that anti-lyric conceptual poems such as Fitterman’s, Jaeger’s, or Goldsmith’s usually present, and risking narrative and characterization. Initially, almost all of its lines are in the second person, the first person, or are impersonal:

You with your one-sided heartache, your dark relationship to nature, your lack of whatever.

A jay, a rook, a parking ticket.

I don’t know what you felt. (9)

But by the book’s closing pages the “I” has disappeared; almost all the lines are in the second person. The triplet of noun phrases here – “a jay, a rook, a parking ticket” – recurs in a different vocabulary – sometimes with much longer noun phrases – on almost every page. The lines alternate roman and italic typeface throughout, but when a line is repeated (none, I believe, more than once) it is in the other face. These recurrences plus the syntactic similarities between the roman and italic lines prevent a reader from assuming that the two fonts represent different ‘voices.’ The font alternation seems to function mainly to organize the text visually, make the lines seem more discrete, and amplify the disjunctions between them.

The poem's second person pronoun usually implies a person, readable through the consistent attributions of anxiety it receives as a single person. The impersonal lines add to the sense of discontinuity of argument while also, especially the triplet noun phrases, creating a contrasting sameness of context. A few of the first-person statements are direct contradictions expressed in identical syntax. Some pages have numerous questions, such as p. 62, where there are seven, all of them in italicized lines; some pages have none. Some lines imply sequentiality, such as a series of italicized statements beginning with “Then” (54); most imply a temporally indeterminate condition of doubt and conflicted subjectivity.

Many of the lines are marked by what is effectively an initial word rhyming, such as the “Then” just noted. The opening pages have almost half their lines beginning “A gate made of” – which provide a kind of chorus later whenever one of them is repeated. Other lines will repeatedly begin with “Now,” or “For you,” or “Feminism” or – most frequently – “You.” All these textual elements recurrently remind the reader that this is a made text, a sculptured text, as well as one that is shifting and evolving in form – that there is much in the materiality of the text to reflect upon. The accumulating patterns, repetitions and changes in repetition may overwhelm a reader’s ability to recall and track them, but still nevertheless engage by creating the impression that things are happening in the text beyond the mere accumulation that much conceptual poetry provides.

Cinema of the Present is thus indirectly a poem about conceptual poetics, seemingly a swerve away from its anti-lyricism, and a potential contribution to its controversies. It also directly engages poetics – many of the exchanges between “I” and “you” or between “you” and itself are about how to be a woman poet in the present – subject matter that could have been that of Dorothy Wordsworth. Its forerunner in Canadian Lit is probably not any long poem but Gail Scott's novel Heroine.

FD

RSS Feed

RSS Feed