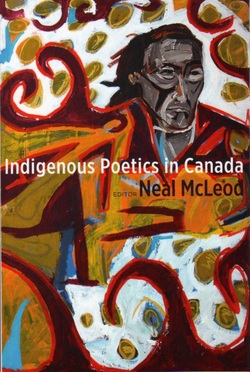

Cree poet Neal McLeod has gathered together essays by, and interviews with, various Indigenous poets and trusted non-Indigenous readers on the subject of Indigenous poetics. Many of the contributors express discomfort with the latter word, however. When asked to “define Indigenous poetics,” Chippewa poet and publisher Kateri Akiwenzie-Damm replies “I’m sort of hung up on that whole concept of poetics and what does it mean in an Indigenous context” (266). Métis poet and Canada Research Chair Warren Cariou notes the word’s origin in Aristotle, “a drawer of boundaries,” and adds “Sometimes that makes me wish Indigenous artists had a different word for the thing he defined as poetics” (31). Onondaga scholar David Newhouse begins with the disclaimer “Poetics – and particularly Indigenous poetics – has not been a part of my formal education, which has been primarily in the sciences and social sciences. I am more comfortable with the knowledge paradigms and truth traditions embedded in them than I am with the interpretative and hermeneutic underpinnings of the humanities” (73). The sciences, of course, and European notions of objective truth, have their origin in the categorizings of Aristotle.

Many other contributors avoid using the word altogether. Those who use it most often employ it as a synonym for philosophy or world view – “the voices of our ancestors” (Tasha Beeds 65), “ways of knowing” (Christine Sy 187 – who also writes of a “poetics of personal decolonization” 185), a “praxis” that resides “not only in our cultural and spiritual inheritances and legacies but also our intellectual and narrative traditions (James Sinclair 208). “When we sing, the bones of our ancestors hear our songs and they work their way to the surface of the land, singing themselves up” writes Lee Maracle (305).

In his 1997 study of Maurice Blanchot, Gerald Bruns contemplates the origins of Aristotle’s terms poesis and poetics, and suggests that they were part of an unsuccessful strategy of containment, a way of domesticating an unruly

Possibly only in a culture already philosophical in its deep structure – already, for example, deeply committed to the principle of non-contradiction and the grasping of things by means of concepts – could the subject or practice of poetry arise, for example, as the possibility of transgression, or (as in this book) as the language of the singular or nonidentical. “Only within metaphysics is there the metaphorical,” says Heidegger, meaning that the very distinction between the literal and the figurative, as between the poetic and the non-poetic, or between poetry and philosophy, presupposes the institution of philosophy as, in some sense, a theory or practice of the rationality, the ruliness, of discourse. (Bruns 4-5)

Well-meaning efforts by some current critics to link Indigenous poetries to the North American avant-garde poetries descended from such ‘shock the bourgeoisie’ poets as Mallarmé, Rimbaud, and Baudelaire, merely because both poetries offer radical critiques of Western culture, are badly conceived. There is nothing ‘avant’ about the poetics – or the world views – implied in McLeod's collection. “Back” is the more characteristic word. Several of the writers view Indigenous culture as currently diasporic both geographically and spiritually. “One of the challenges of contemporary Indigenous poetics is to move from a state of wandering and uprootedness toward a poetics of being at home,” writes editor McLeod (10). Taking note of the suffering of Indigenous peoples from social “dysfunction, poverty and addiction,” Tasha Beeds writes of the need “to find our way back (my italics) to our teachings from these spiritual and ideological diasporas” (66).

What is poetics? Several of the contributors, wary of the universities and professional critics, remark that poetics is not literary criticism. But in fact this is one of the current Oxford dictionary meanings of poetics, Aristotle’s own understanding when writing his catalog of literary forms, and very much still evident in works such as Tzvetan Todorov’s The Poetics of Prose or Mark Axelrod’s The Poetics of Novels: Fiction and its Execution.

For many current poets, however, poetics is primarily a theory of how to write poetry, familiar at least since Wordsworth’s declaration that poetry should be written in “the real language of men” and Keats’ that poetry is best written when the poet “is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” In the last century there was Eliot’s recommendation of impersonal poetry that was an “escape from emotion,” Olson’s of allowing one perception to “immediately and directly lead to a further perception,” and Duncan’s of “tone-leading” – the following the dominant phonemes of one’s lines toward unexpected words and content. This kind of highly specific process-focussed conception of poetics is one which none of the poets in this collection considers – which again indicates how foreign to them is the Euro-American avant-garde with its individualism and practice-defined groups. That difference is worth watching and respecting.

FD

RSS Feed

RSS Feed