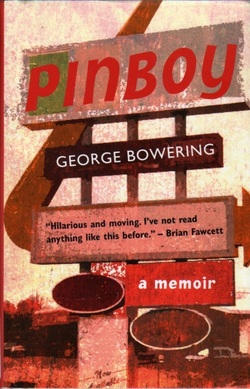

I was late in reading George Bowering’s 2012 book Pinboy, one catalogued for libraries as “biography” and billed by its publisher as a “memoir” in which “Bowering’s youth provides signs of the writer he grew up to be” – i.e. as one which encourages a reader to assume that the narrator, author and protagonist are all the same person. I wasn’t all that curious about my old friend’s adolescence.

On Amazon.ca, however, some readers were not only curious but very concerned about the narrative’s possible authenticity. “I grew up in this little town [Oliver, BC] so could tell the story is authentic,” reader Diana Haynes wrote. Reader Buryl Slack, also from Oliver, believed the narrative should have been even more historical and authentic. “This book was written by the author in order to get revenge, and comeuppance. In some cases he has deliberately semi disguised names and people, in others he has outright named, described and distorted events,” she wrote. Slack seems also to have noticed a few metafictional passages (not her terminology) that subvert the narrative’s implications of truth-telling, but these in her view don’t atone for the distortions. “[E]ven though the author in his garbled fashion of writing this book says a great deal of it is untrue, what he has done is unforgettable and unpardonable.”

One of these passages occurs at the opening to the third chapter, and covertly weakens (a kind of garbling, I suppose, if you miss it) the link between author George Bowering and the narrator/protagonist of the identical name. The narrator is deriding US novelist Jerome Charyn for having described his three-volume memoir as largely written by “imaginative recreation” and the people in it as “characters.” “Well, I don’t have to tell you that I don’t have any power of imagination,” Bowering’s narrator goes on to declare. “I am not recreating any of this stuff. I think it all happened.”

I think Pinboy has been extremely badly served by being published as a “memoir.” It reads as every bit as much a novel as Robert Creeley’s The Island, Gail Scott’s Heroine, or Daphne Marlatt’s Ana Historic, and is thematically equally provocative. Bowering shapes the text around three concurrent relationships that young (15 years old) “George Bowering” has with women – the very self-contained teenager Wendy Love (who corresponds the historic Wendy Amor of Bowering’s biography), his school classmate from the wrong-side-of-town Jeannette MacArthur, and a teacher at his high school, “Miss Verge.” He places these relationships against the dark background of the unexplained deaths of Wendy’s previous boyfriend, an athletic skier, and of a local champion swimmer. Young protagonist Bowering imagines himself in love with Wendy (in love with love?) but is more likely attracted by the exoticism of her British backround and accent and her seemingly cold and untroubled confidence. He’s not sure about this. He shows most fascination with Jeannette, who is likely a long-abused child, and with the angry directness of her gaze and speech whenever he can press her to communicate. He believes he is only charitably wanting to help her, and naively discounts how strongly he seems to desire her as an honest conversation-mate. She, and along with her speech, language, discourse (things with which Wendy is overly economical) are what he most appears driven to want intimacy with.

He is baffled by the sexual aggressiveness of Miss Verge – who speaks most expressively in grunts and cries, and who in a sense is also a polar opposite of both Wendy and ‘love’ – who in amusingly rendered scenes exploits his otherwise unanswered sexual curiosity with an energy, slyness and boldness that borders on rape, and probably constituted at least statutory rape in the decade depicted. This gap between what the protagonist can understand about himself and his relationships and what the author enables the reader to perceive about them is another element that makes this book fiction rather than memoir. The protagonist/narrator knows only that the events happened but the author presents them so the reader can both know them and glimpse understandings of them.

I found the book’s ending saddening. Protagonist George is still pursuing the emotionally unavailable and discursively economical Wendy. Miss Verge appears to have been discreetly dismissed from the school – like child-abusing priests in this period, and later, were moved from parish to parish. Jeannette and her violent father, who has twice assaulted George, once with a rifle and once breaking his arm with a bat, have vanished. George fears she may be dead. Violent sex and violent death do happen here. The reader may have difficulty deciding which of the three plot conclusions is the most disappointing. Protagonist George concludes for us the Jeannette story first but is pondering only the Wendy one when the book closes.

If the book had been packaged as a novel, it could well have been received as a timely story of family violence and child abuse. Instead it has been read as both an unwelcome exposé of the helpless dead and as an “hilariously accurate” (Bowering’s close friend Brian Fawcett, on the back cover) self-portrayal of the author’s enviably adventurous adolescence. The Globe & Mail reviewer nominated it for the Stephen Leacock Medal for Humour. That medal would have been dark humour indeed for enviably clever dark humour.

FD

RSS Feed

RSS Feed